Advancing regulatory variant effect prediction with AlphaGenome

Authors: Žiga Avsec, Natasha Latysheva, Jun Cheng, Guido Novati, Kyle R. Taylor, Tom Ward, Clare Bycroft, Lauren Nicolaisen, Eirini Arvaniti, Joshua Pan, Raina Thomas, Vincent Dutordoir, Matteo Perino, Soham De, Alexander Karollus, Adam Gayoso, Toby Sargeant, Anne Mottram, Lai Hong Wong, Pavol Drotár, Adam Kosiorek, Andrew Senior, Richard Tanburn, Taylor Applebaum, Souradeep Basu, Demis Hassabis & Pushmeet Kohli

Paper: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41586-025-10014-0

Code: https://github.com/google-deepmind/alphagenome_research

Model: http://deepmind.google.com/science/alphagenome

TL;DR

WHAT was done? The authors introduce AlphaGenome, a unified deep learning model that processes 1 Megabase (Mb) of DNA sequence to predict 5,930 functional genomic tracks (including RNA-seq, splicing, and chromatin features) at single-base resolution. By utilizing a U-Net-inspired architecture with a Transformer bottleneck and a distillation training strategy, the model achieves state-of-the-art performance in both track prediction and variant effect prediction (VEP).

WHY it matters? Previous sequence-to-function models faced a hard trade-off: they either offered high resolution with short context (e.g., SpliceAI) or long context with low resolution (e.g., Enformer). AlphaGenome resolves this dichotomy, allowing researchers to simultaneously model fine-grained mechanisms like splicing and long-range interactions like enhancer-promoter looping in a single inference pass.

Details

The Resolution-Context Trade-off

A persistent engineering bottleneck in computational biology has been the tension between the receptive field of a model and its output resolution. Deep learning models designed to decode the regulatory genome typically fall into two distinct camps. On one side are base-resolution models like SpliceAI and BPNet, which predict precise molecular events but are computationally restricted to short input sequences (often <10 kb). This limitation blinds them to distal regulatory elements, such as enhancers located hundreds of kilobases away. On the other side are “large context” models like Enformer and Borzoi, which ingest roughly 200–500 kb of sequence but output predictions in coarse bins (e.g., 128 bp). This binning averages out critical signal, making it difficult to resolve specific transcription factor binding sites or splice junctions. AlphaGenome addresses this by scaling the input context to 1 Mb while maintaining single-base output resolution, effectively unifying these disparate modeling paradigms.

Architecture: A Dual-Representation U-Net

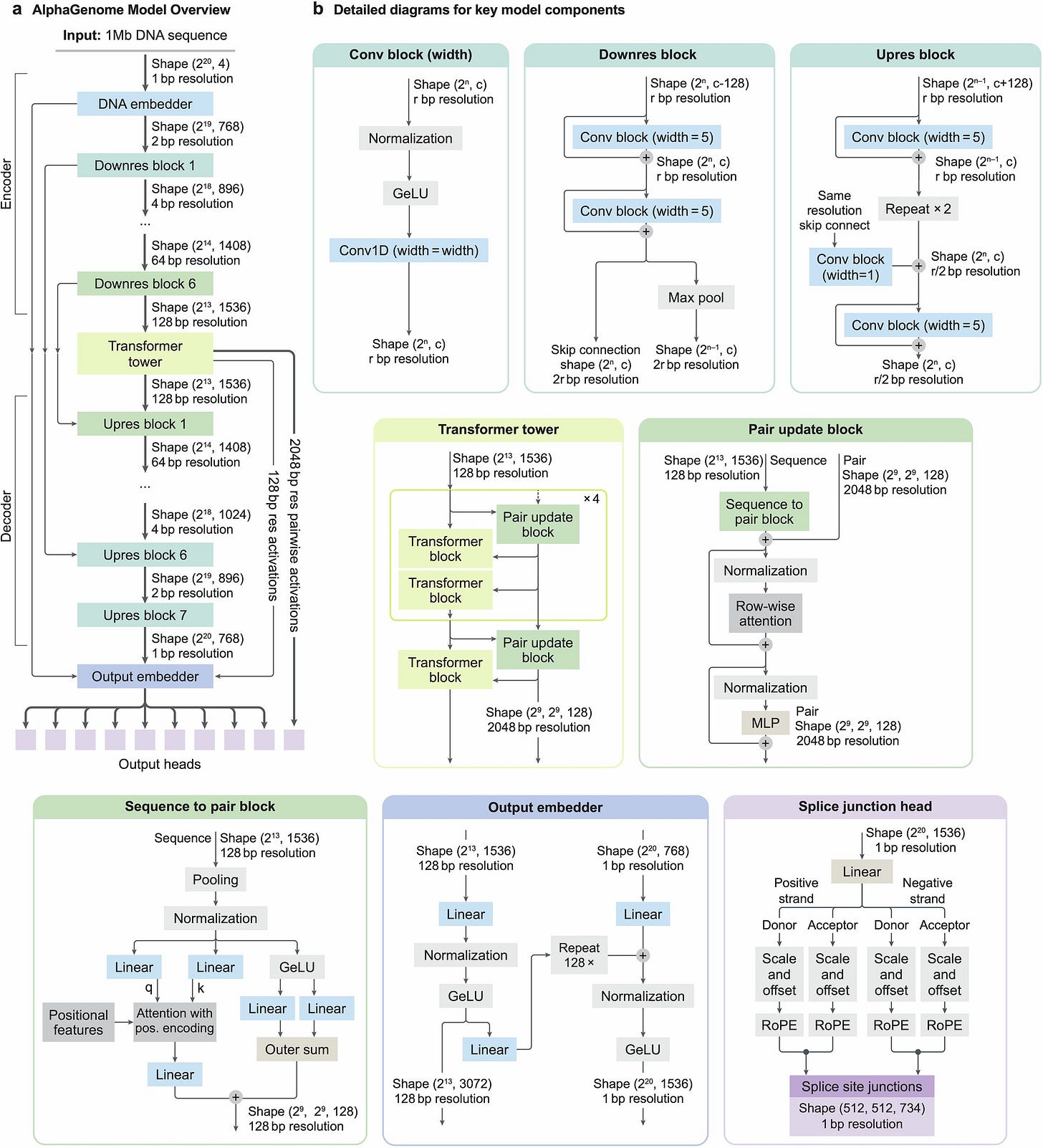

At its core, AlphaGenome treats the genome as both a linear sequence and a set of spatial interactions. The architecture, illustrated in Figure 1a and Extended Data Figure 1, is a U-Net-style encoder-decoder network that maintains two distinct latent representations. The input is a one-hot encoded DNA sequence X∈{0,1}L×4, where L=106 (1 Mb). The encoder uses convolutional blocks to downsample this sequence from 1 bp resolution to 128 bp resolution.

In the bottleneck of the U-Net, the model employs a “Transformer Tower.” This component processes the compressed 128 bp embeddings to capture long-range dependencies, such as the interaction between a distal enhancer and a gene promoter. Uniquely, this stage generates two types of embeddings: a 1D embedding representing the linear genome state and a 2D embedding (at 2,048 bp resolution) representing pairwise interactions, which is used to predict chromatin contact maps (Hi-C). The decoder then progressively upsamples the 1D embeddings back to the original 1 bp resolution using skip connections from the encoder to retain high-frequency spatial information. This dual-pathway approach ensures that the model can predict contact maps and linear tracks (like RNA-seq or ATAC-seq) simultaneously without sacrificing the granularity required for splicing predictions.

Engineering Scale: Parallelism and Distillation

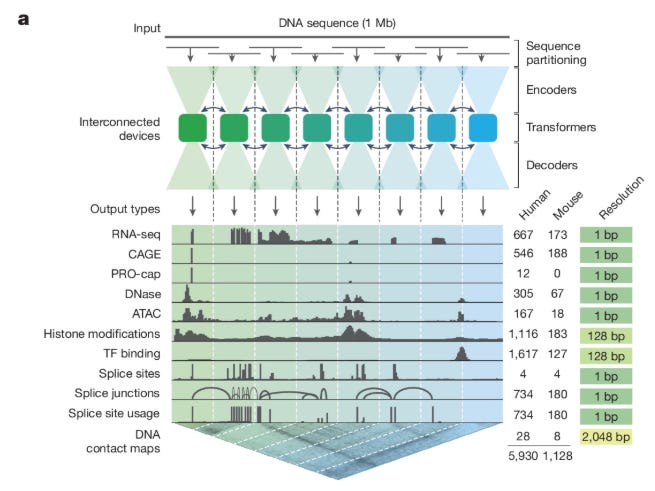

Training a model on 1 Mb sequences at base-pair resolution presents significant memory challenges. To manage the dense activations required for the U-Net decoder, the authors implemented sequence parallelism across eight interconnected TPU v3 devices. The 1 Mb input is partitioned into 131 kb chunks, with each device processing a specific genomic interval. The Transformer layers in the bottleneck facilitate communication across these devices, ensuring that the effective receptive field covers the full megabase despite the physical partitioning.

A critical innovation in AlphaGenome’s deployment is its two-stage training regime, detailed in Figure 1b and 1c. Initially, “teacher” models are trained using cross-validation folds. However, using an ensemble of large models for inference is computationally expensive. To solve this, the authors employ knowledge distillation. A single “student” model is trained to predict the outputs of the ensemble of teacher models. The student is exposed to augmented data—random shifts, reverse complements, and random mutations—which forces it to learn a robust manifold of the decision boundary.

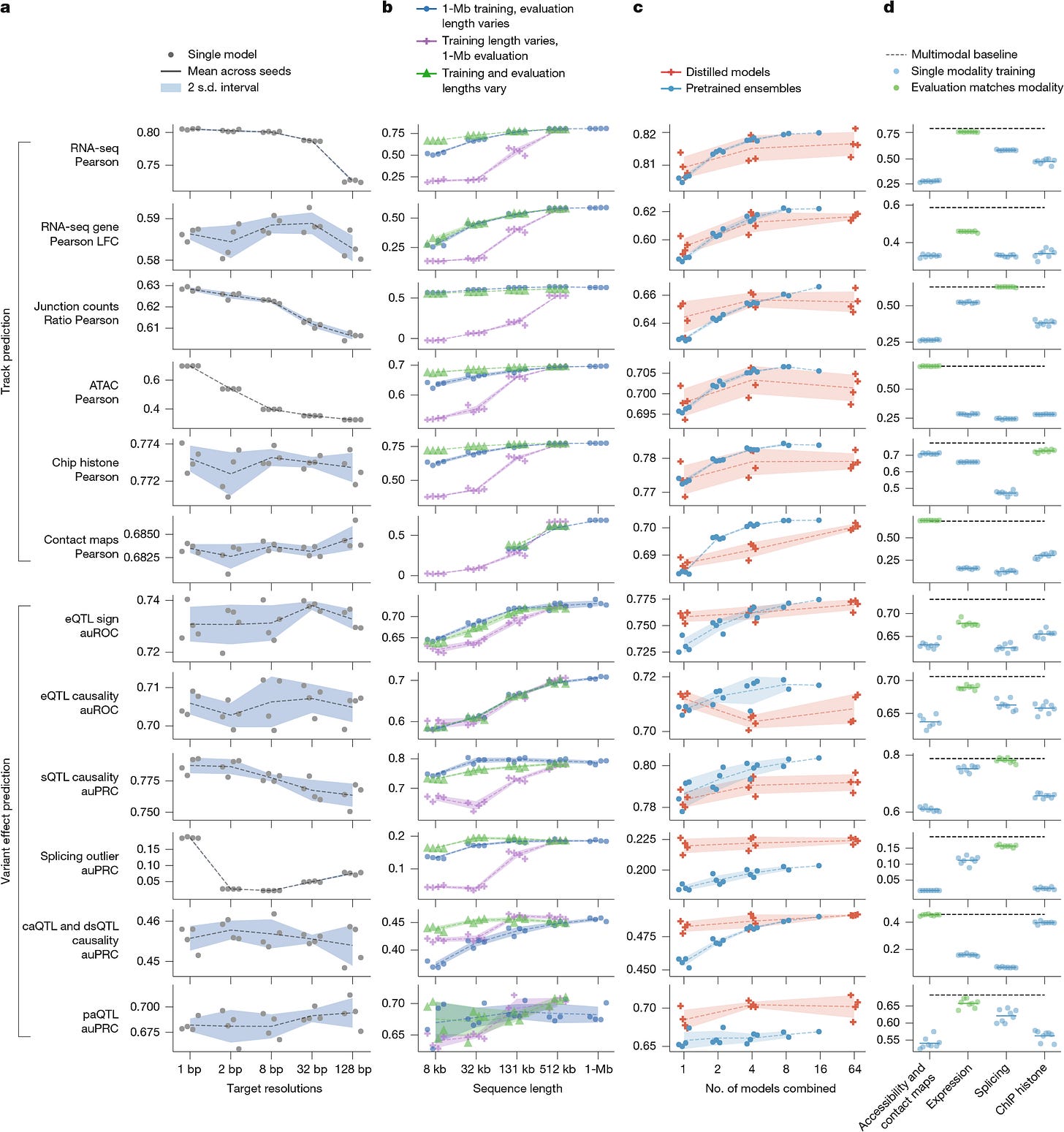

As shown in Figure 7c, the distilled student model matches or exceeds the performance of the teacher ensemble while requiring significantly less compute at inference time (less than 1 second per variant on an H100 GPU).

Splicing: Beyond Simple Track Prediction

While most genomic tracks (e.g., ChIP-seq coverage) are predicted via linear projection of the final embeddings, splicing requires a specialized head. AlphaGenome predicts three distinct splicing features: splice site presence (is nucleotide i a donor/acceptor?), splice site usage (how often is it used?), and splice junctions (does site i connect to site j?).

The splice junction prediction is particularly notable because it requires modeling pairwise relationships between potential donor and acceptor sites. As depicted in Extended Data Figure 1, the model computes interactions between the 1D embeddings of candidate donor-acceptor pairs to predict the junction count. This allows AlphaGenome to capture the competitive nature of splicing regulation—where a variant might not destroy a splice site but simply make a nearby decoy site more attractive—a phenomenon often missed by models that only predict local splice site strength.

Mechanistic Validation and Ablation

The authors validate the model’s mechanistic understanding through extensive ablation studies and specific biological case studies. Figure 7a (above) demonstrates that training at 1 bp resolution is essential for performance on high-frequency signals like splicing (PSI5/PSI3) and ATAC-seq, whereas coarser tasks like histone modification correlations are less sensitive to resolution. Furthermore, Figure 7b confirms that the 1 Mb context is strictly necessary; models trained on shorter contexts (e.g., 32 kb) fail to generalize even when evaluated on longer sequences.

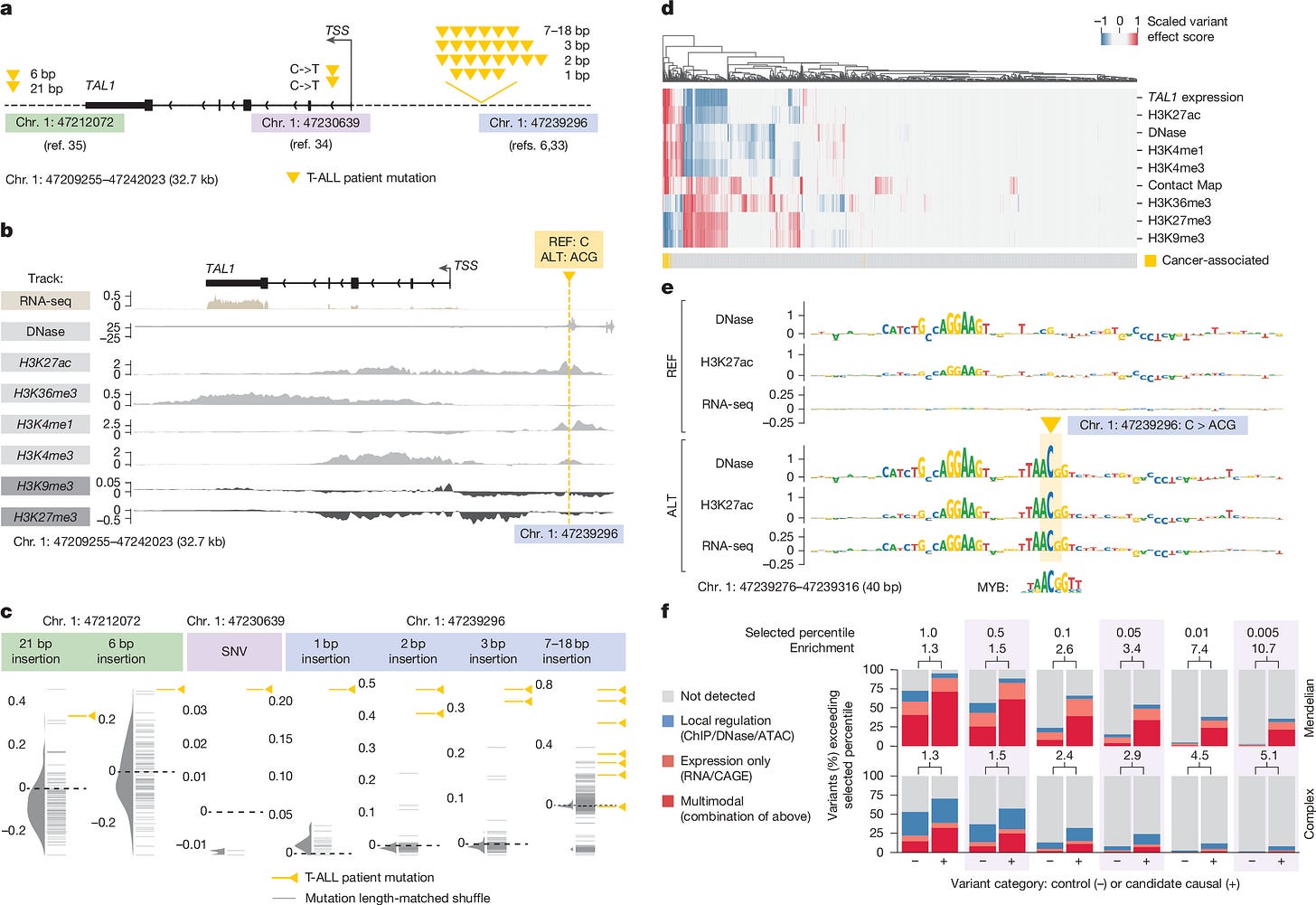

A compelling validation is provided in Figure 6, where the model analyzes variants near the TAL1 oncogene. The model correctly predicts that a specific non-coding mutation (chr1:47239296 C>ACG) introduces a MYB binding motif. Crucially, because the model is multimodal, it predicts not only the creation of the binding site but also the downstream consequences: an increase in local H3K27ac (activation) and a specific upregulation of TAL1 expression, aligning perfectly with experimental observations in T-cell acute lymphoblastic leukemia.

Related Works

AlphaGenome builds upon a rich lineage of sequence-to-function models. It integrates the high-resolution convolutional approach of DeepSEA, BPNet, and SpliceAI with the Transformer-based long-context modeling introduced by Enformer. It directly competes with and outperforms Borzoi, particularly in fine-grained tasks like splicing and splice-site usage, where Borzoi’s coarser resolution is a limitation. It also outperforms Pangolin on specific splicing benchmarks, demonstrating that a generalist model can now rival specialized architectures.

Limitations

Despite the impressive unification of scale and resolution, AlphaGenome remains bound by the constraints of current sequence-based deep learning. The model captures cis-regulatory effects within a 1 Mb window, but distal regulation beyond this horizon remains out of reach. Additionally, the model is trained primarily on human and mouse reference genomes, limiting its immediate applicability to other species without retraining. While the distillation process improves robustness, the computational cost of the initial training phase (involving ensembles of teachers on TPU pods) remains high, potentially limiting the ability of smaller labs to retrain or fine-tune the model on private datasets. Finally, as with all correlation-based models trained on reference genomes, predicting the impact of variants on personal genomes (which may have completely different structural variations) remains a frontier challenge.

Conclusion

AlphaGenome represents a significant consolidation in the field of regulatory genomics. By successfully engineering a model that does not compromise on resolution to achieve context, the authors have provided a “foundation model” utility for variant effect prediction. The move toward a distilled, efficient student model for inference signals a maturation of the field, shifting focus from pure architectural novelty to practical, scalable deployment for clinical and research applications. For researchers analyzing non-coding variants, AlphaGenome likely renders the practice of running separate models for splicing, expression, and chromatin state obsolete.