Bolmo: Byteifying the Next Generation of Language Models

Authors: Benjamin Minixhofer, Tyler Murray, Tomasz Limisiewicz, Anna Korhonen, Luke Zettlemoyer, Noah A. Smith, Edoardo M. Ponti, Luca Soldaini, Valentin Hofmann

Paper: https://arxiv.org/abs/2512.15586

Code: https://github.com/allenai/bolmo-core

Model: https://huggingface.co/allenai/Bolmo-7B

TL;DR

WHAT was done? The authors introduce Bolmo, a family of byte-level language models (1B and 7B) created not by training from scratch, but by “byteifying” existing subword models (Olmo 3). By replacing the embedding and tokenizer layers of a pre-trained Transformer with lightweight, local Recurrent Neural Networks (mLSTMs) and employing a two-stage distillation process, they convert a subword model to a byte-level model using less than 1% of the original pre-training token budget.

WHY it matters? Byte-level models (BLMs) theoretically solve major issues like tokenization bias, vocabulary bottlenecks, and character blindness, but they have historically been prohibitively expensive to train to state-of-the-art levels. This work provides a generalizable recipe to “retrofit” high-performance subword models into byte-level models efficiently. Crucially, it demonstrates that these retrofitted models can inherit the post-training ecosystem (e.g., instruction tuning) of their parents via weight merging, bypassing the need to rebuild the entire safety and alignment pipeline for byte-level architectures.

Details

The Tokenization Bottleneck and the “Valley of Death”

The current paradigm of Large Language Models relies heavily on subword tokenization (like BPE), a heuristic compression step that maps text to a fixed vocabulary of integers. While efficient, this introduces severe artifacts: models struggle with character-level tasks (e.g., “reverse the word ‘lollipop’”), exhibit brittle behavior on out-of-vocabulary terms, and suffer from “tokenization bias” where simple whitespace changes alter generation significantly. The theoretical solution has long been Byte-Level Language Models (BLMs), which operate directly on UTF-8 bytes.

However, BLMs face a “Valley of Death” in adoption. Training a competitive 7B parameter model from scratch on bytes requires immense compute—typically 4× to 8× the sequence length of subword models—and by the time a research lab trains a competitive BLM, the industry standard for subword models has already moved on. The authors of Bolmo circumvent this race by proposing Byteification: a mechanism to transplant the “brain” (global Transformer layers) of a state-of-the-art subword model into a byte-level “body” (local encoder/decoder), avoiding the need to relearn world knowledge from scratch.

Architecture First Principles: The Latent Tokenizer

Bolmo builds upon the Latent Tokenizer Language Model (LTLM) framework, similar to MegaByte or Byte Latent Transformer (review). The core assumption is that while the global model benefits from high-level semantic “patches” (analogous to tokens), the mapping from raw bytes to these patches should be learned and dynamic rather than fixed by a heuristic tokenizer.

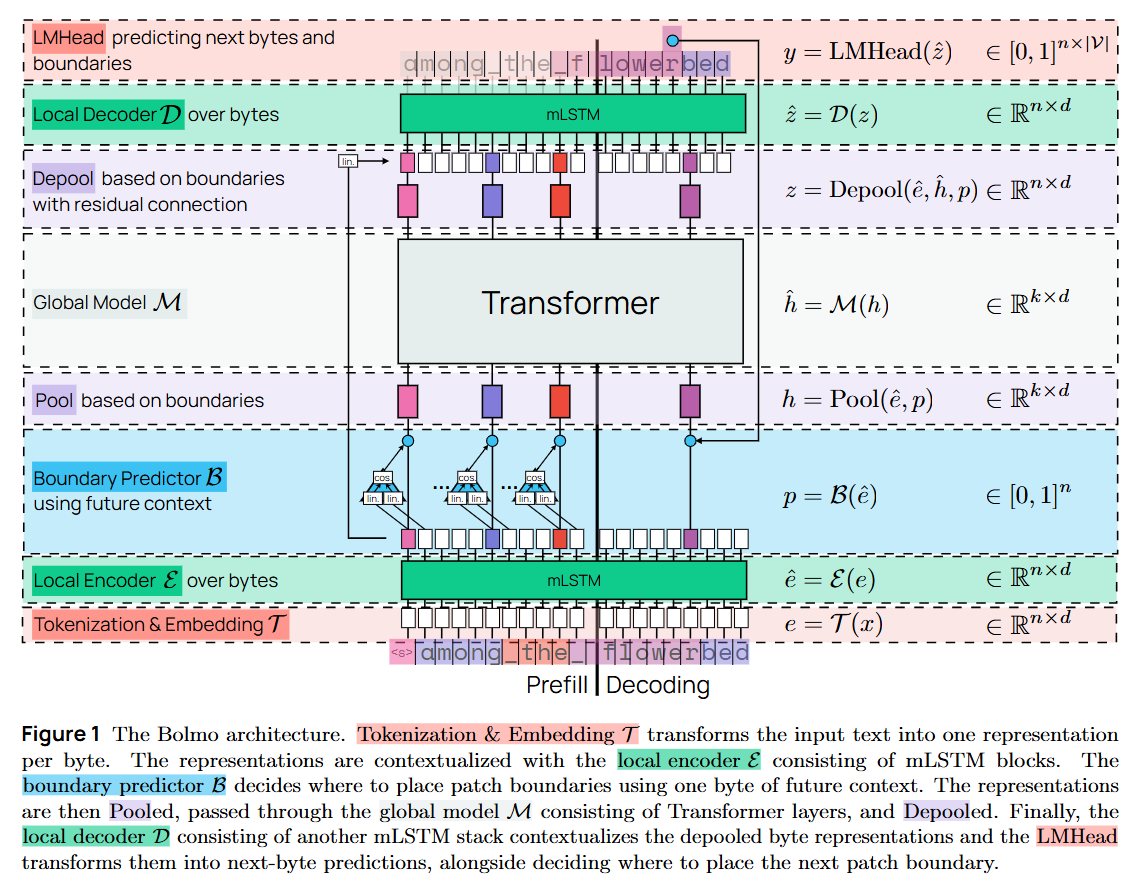

The architecture processes a sequence of bytes through three distinct stages. First, a Local Encoder E ingests raw bytes and contextualizes them into a dense representation; Bolmo utilizes mLSTM (from the xLSTM family) here for its parallelizability and inference speed. Second, a Boundary Predictor B decides which bytes constitute the end of a patch, effectively acting as a learned tokenizer. These patch representations are then pooled and passed to the Global Model M, the heavy, pre-trained Transformer (e.g., Olmo 3) that processes the data. Finally, a Local Decoder D takes the global output and autoregressively generates the constituent bytes of the next patch. Crucially, the authors retain the original subword embeddings of the parent model. The input to the global model is a summation of the learned local encoder output and the original subword embedding for the corresponding span. This acts as a residual connection to the parent model’s latent space, stabilizing the transfer.

The Mechanism: Non-Causal Boundaries and Distillation

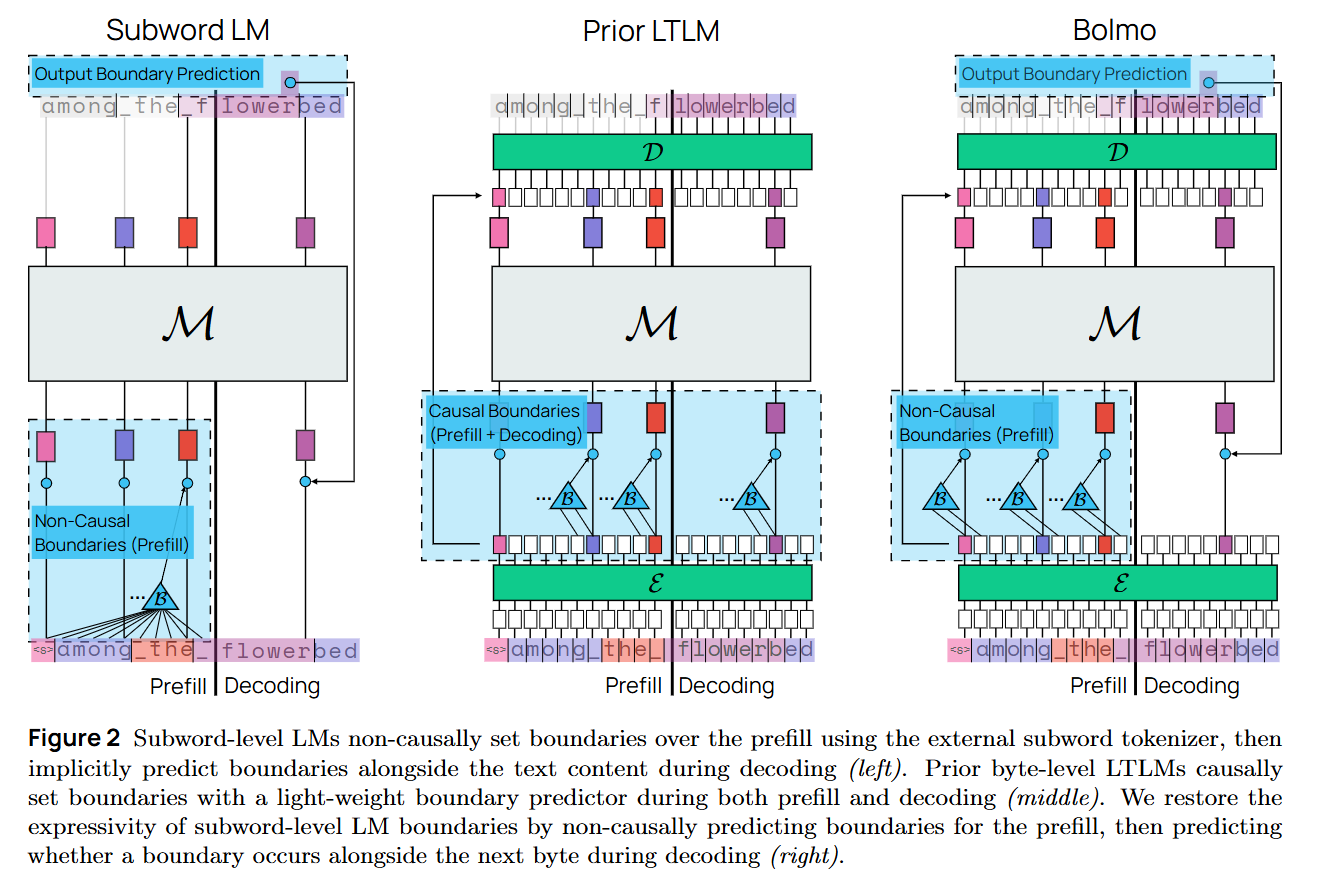

The central technical challenge in retrofitting is the impedance mismatch between subword tokenization and causal byte-level modeling. Standard BPE tokenizers are non-causal during the pre-processing stage; they look ahead to decide if “The” and “re” should be merged into “There”. A standard causal BLM cannot see the future byte to make this decision, leading to misaligned patch boundaries during distillation.

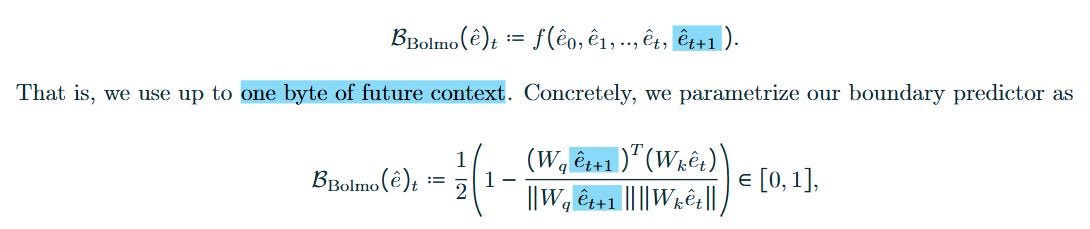

To solve this, Bolmo introduces Non-Causal Patch Boundary Prediction during the prefill phase. The boundary predictor B utilizes one byte of future context to align its patch decisions with the source model’s tokenizer. Formally, the probability of a boundary at step t is parametrized as:

By peeking at êt+1, the model can perfectly emulate BPE boundaries (e.g., knowing not to split a prefix if the next letter completes a known subword). As illustrated in Figure 2, this allows the local encoder to produce patch representations that map one-to-one with the parent model’s input expectations. During decoding (generation), the model switches to a causal mode where the Local Decoder explicitly predicts a special <b> (boundary) symbol to signal the end of a patch.

The training pipeline proceeds in two distinct phases. Stage 1 (Distillation) freezes the Global Model M while the Local Encoder and Decoder are trained to minimize the KL-divergence between the Bolmo patch logits and the source Olmo subword logits. This forces the local modules to act as perfect translators for the frozen transformer. Subsequently, Stage 2 (End-to-End) unfreezes the entire model and trains it on a small subset of tokens (39B tokens, <1% of Olmo 3’s budget), allowing the global attention weights to adapt to the slight distributional shifts of the neural tokenizer.

Training Stability and Efficiency

The choice of the mLSTM (multi-head LSTM) for the local encoder and decoder is a critical engineering decision. Unlike standard Transformers, mLSTMs offer linear complexity with respect to sequence length and, crucially for the local decoder, efficient caching state updates. This mitigates the inference latency penalty typically associated with the finer granularity of bytes.

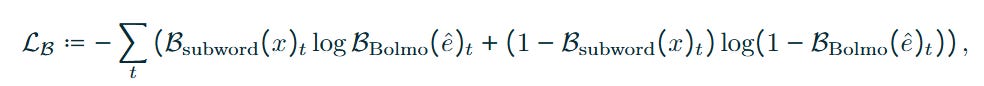

To validate the efficiency of the “byteification” process, the authors utilize a loss function that combines boundary supervision (matching BPE boundaries initially) with next-byte prediction. The boundary loss LB is defined as:

This supervised approach to boundaries stabilizes the early training dynamics, preventing the “collapse” often seen in LTLMs where the model assigns trivial patch lengths.

Analysis: The Source of Performance

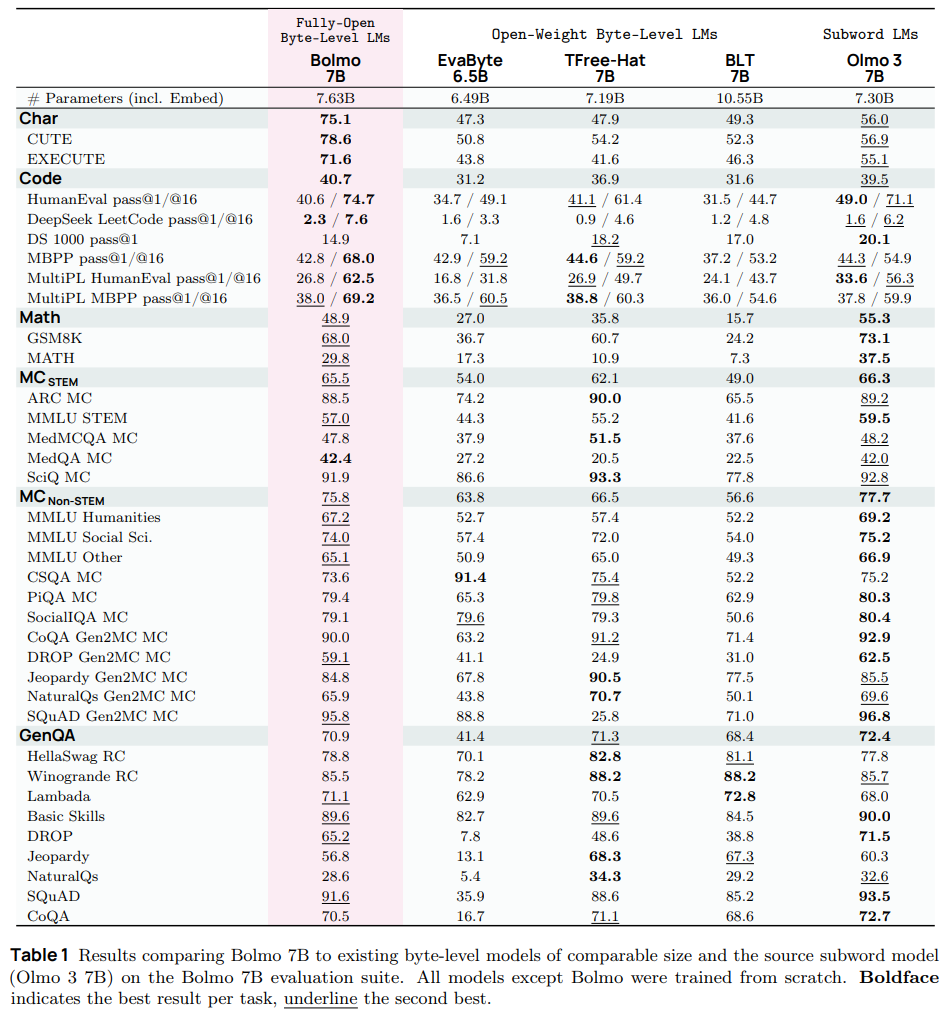

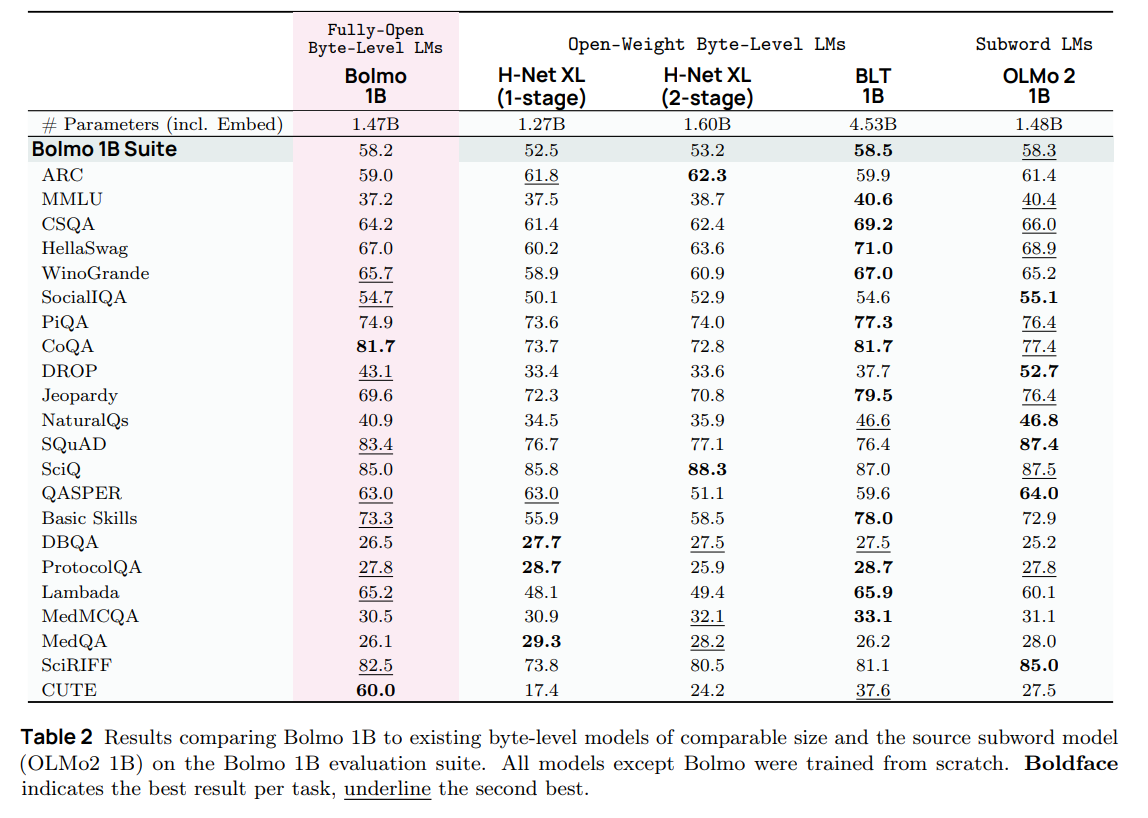

The results presented in Table 1 and Table 2 confirm the efficacy of this approach.

Bolmo 7B outperforms Byte Latent Transformer (a comparable model trained from scratch) by significant margins, particularly in STEM tasks (+16.5%).

More interestingly, Bolmo outperforms its parent (Olmo 3) on character-level understanding tasks (e.g., the CUTE benchmark) and coding pass rates (Pass@16). The authors attribute the coding improvements to the elimination of the fixed vocabulary; code often contains variable naming conventions that fragment into inefficient subword sequences, whereas byte-level processing handles arbitrary identifiers natively.

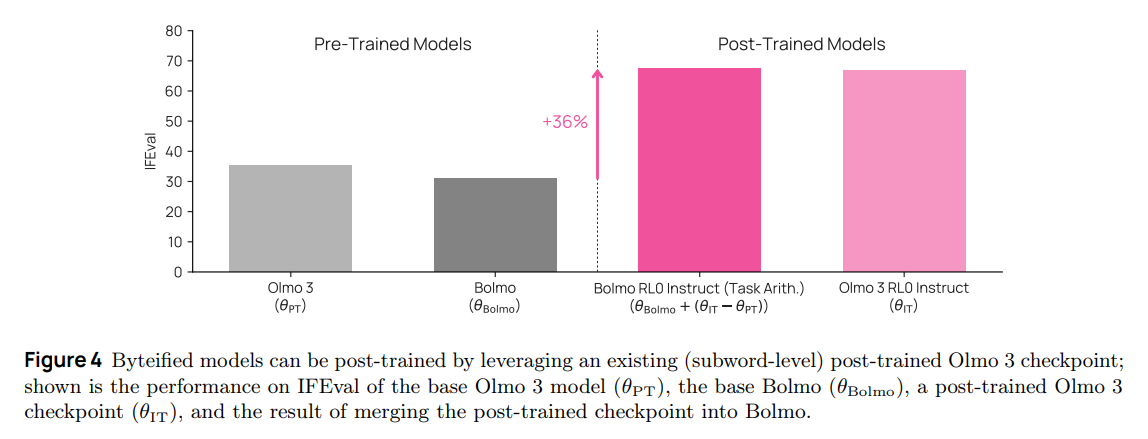

The paper also highlights a unique capability: Post-Training via Task Arithmetic. Because the global weights of Bolmo are topologically identical to Olmo 3 (mostly), the authors show in Figure 4 that one can take the weight delta of an instruction-tuned Olmo 3 and add it to base Bolmo. This successfully transfers instruction-following capabilities to the byte-level model without requiring expensive RLHF runs on the byte-level architecture itself.

Limitations

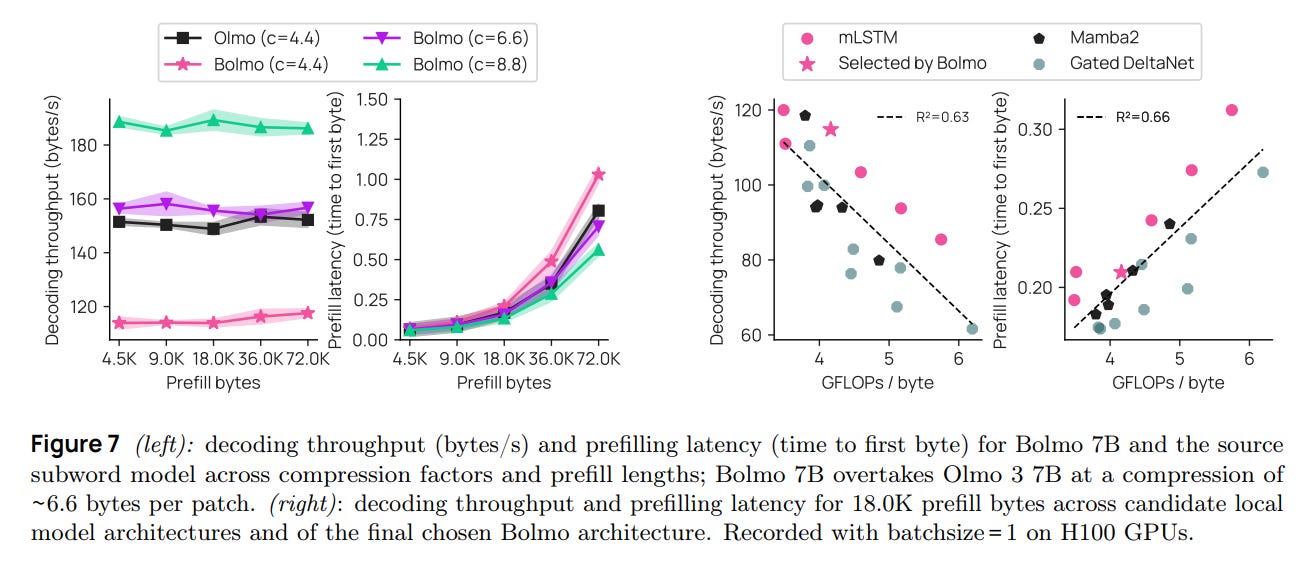

While the prefill speed is competitive due to parallelization, decoding speed remains a challenge. Even with mLSTMs, the model must execute the local decoder multiple times per patch. While the patch generation rate is faster than subword token generation, the sheer volume of bytes means wall-clock time can lag behind highly optimized subword kernels, though Bolmo closes this gap significantly compared to previous attempts.

Furthermore, the reliance on an explicit <b> boundary symbol during decoding introduces a slight discrepancy between the prefill (non-causal, implicit boundaries) and decoding (causal, explicit boundaries) phases. While the authors manage this via boundary symbol fusion (expanding the vocabulary size to 512 to include “byte+boundary” tokens), it adds architectural complexity compared to a pure homogeneous transformer.

Impact & Conclusion

Bolmo represents a strategic pivot in how the field might approach alternative architectures. Rather than viewing Byte-Level LMs as a separate evolutionary tree requiring its own massive pre-training resources, this work frames them as a valid fine-tuning target for existing foundation models.

By reducing the entry cost for high-performance byte-level modeling to a fraction of the original training budget, Bolmo enables researchers to experiment with token-free architectures on top of SOTA baselines (like Llama 3 or Olmo). If the community adopts this “retrofit” pattern, we may finally see the end of the subword tokenization era, not through a single massive training run, but through the gradual conversion of the open-source model ecosystem.

Authors propose a set of future directions (Bit 0 — Bit 7) in Section 8.