Classical billiards can compute

Planar Billiards are Turing Complete

Authors: Eva Miranda and Isaac Ramos

Paper: https://arxiv.org/abs/2512.19156

TL;DR

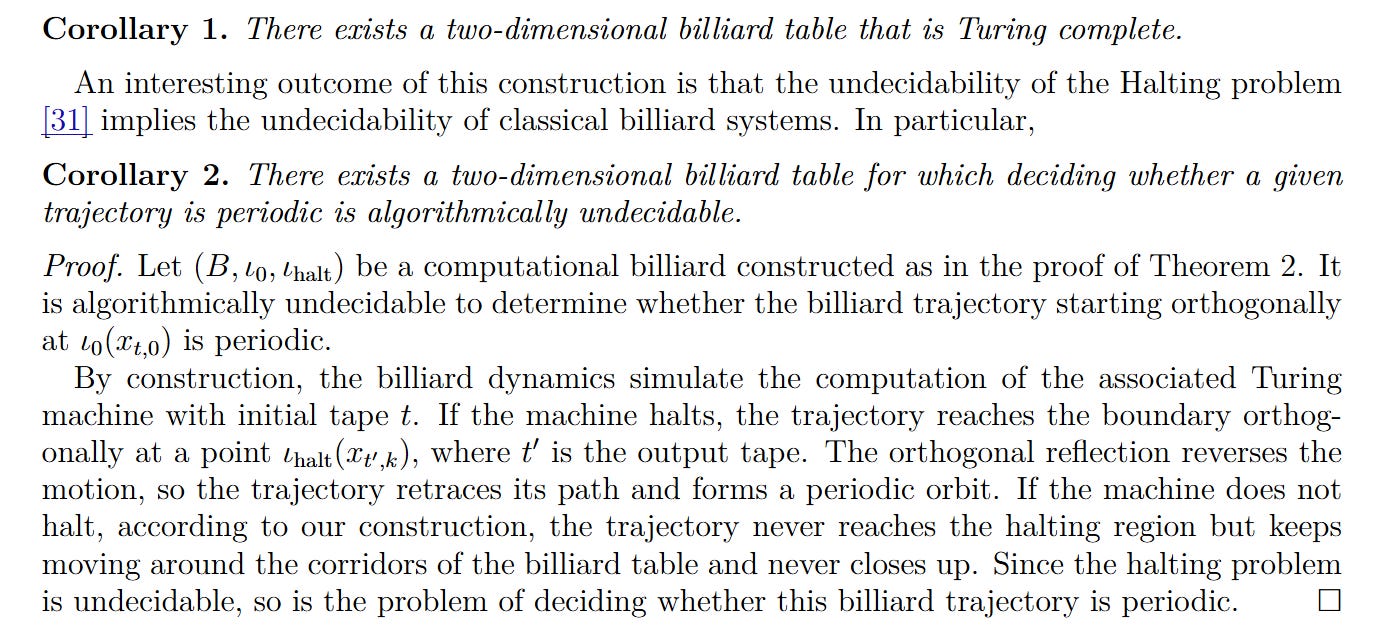

WHAT was done? The authors rigorously prove that a single point particle moving inside a two-dimensional billiard table with fixed polygonal (and parabolic) walls is Turing complete. By adapting the framework of Topological Kleene Field Theory (TKFT), they construct a specific billiard table where the trajectory of the ball simulates the evolution of any given reversible Turing machine.

WHY it matters? This result bridges a significant gap in the physical Church-Turing thesis. While high-dimensional or active systems were known to be universal, it was long conjectured (e.g., by Moore in 1990) that low-dimensional, passive systems might lack the complexity for universal computation. This paper refutes that, demonstrating that undecidability is a fundamental feature of standard Hamiltonian mechanics in dimension two. Consequently, determining whether a specific trajectory is periodic or reaches a target region is algorithmically undecidable, placing a hard logical limit on long-term prediction distinct from the sensitivity to initial conditions found in chaos.

Details

The Dimensionality Threshold in Physical Computation

The question of whether continuous physical systems can embody universal computation has a rich history, tracing back to Feynman and Wolfram. The core challenge lies in embedding the discrete, infinite states of a Turing machine into the continuous phase space of a dynamical system. Previous work has successfully demonstrated Turing completeness in three-dimensional fluid flows (Euler equations) and high-dimensional billiards. However, the planar (2D) case remained an open frontier. Cristopher Moore previously posited in Unpredictability and undecidability in dynamical systems that low-dimensional systems might lie below a “complexity threshold,” incapable of supporting the necessary logical structures without introducing moving walls or many-body interactions.

Miranda and Ramos address this specific bottleneck by proving that a standard 2D billiard—a particle undergoing free motion with specular reflections off fixed boundaries—can indeed compute. This represents a significant delta from prior literature, as it requires neither a third dimension for signal crossing nor active components to manage state. The implication is that the “soft-wall” limits of smooth Hamiltonian systems, such as those found in celestial mechanics or potential wells, may inherently harbor undecidable dynamics.

Encoding The Tape: Cantor Sets in Phase Space

To embed a discrete Turing machine into a continuous 2D space, the authors utilize a specific symbolic encoding. The “Atomic Unit” of this system is the computation state S={(t,q,k)}, where t is the tape content, q is the internal state, and k is the head position. The critical innovation is how the infinite tape t is mapped to a single coordinate in a compact interval I=[0,1].

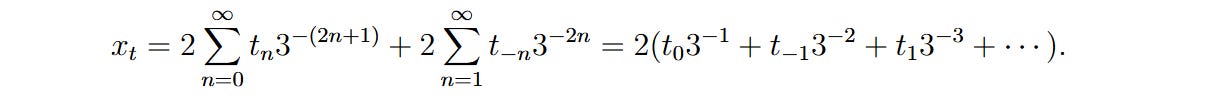

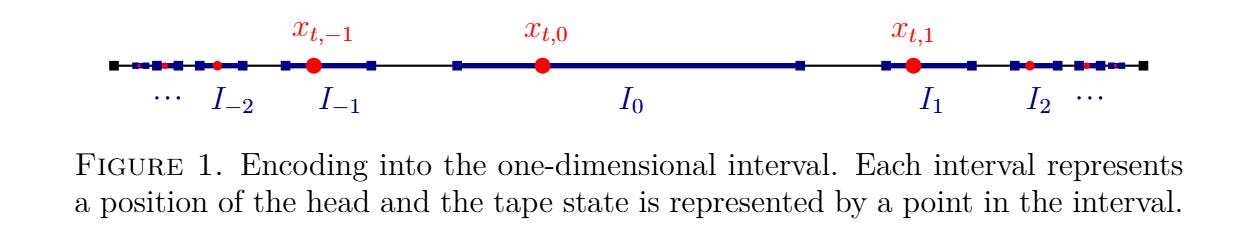

The authors employ a ternary Cantor set encoding. A tape state t={tn}n∈Z (where tn∈{0,1}) is mapped to a real number xt by interleaving the positive and negative halves of the tape into the ternary expansion. Specifically, the right side of the tape occupies odd digits and the left side occupies even digits:

To account for the head position k, this value xt is further mapped into a sub-interval via affine embeddings τk, effectively creating a fractal address space where distinct head positions occupy disjoint segments of the unit interval. This precise encoding allows the physical variable—the collision point on the wall—to carry the full informational content of the machine.

From State Transitions to Specular Reflections

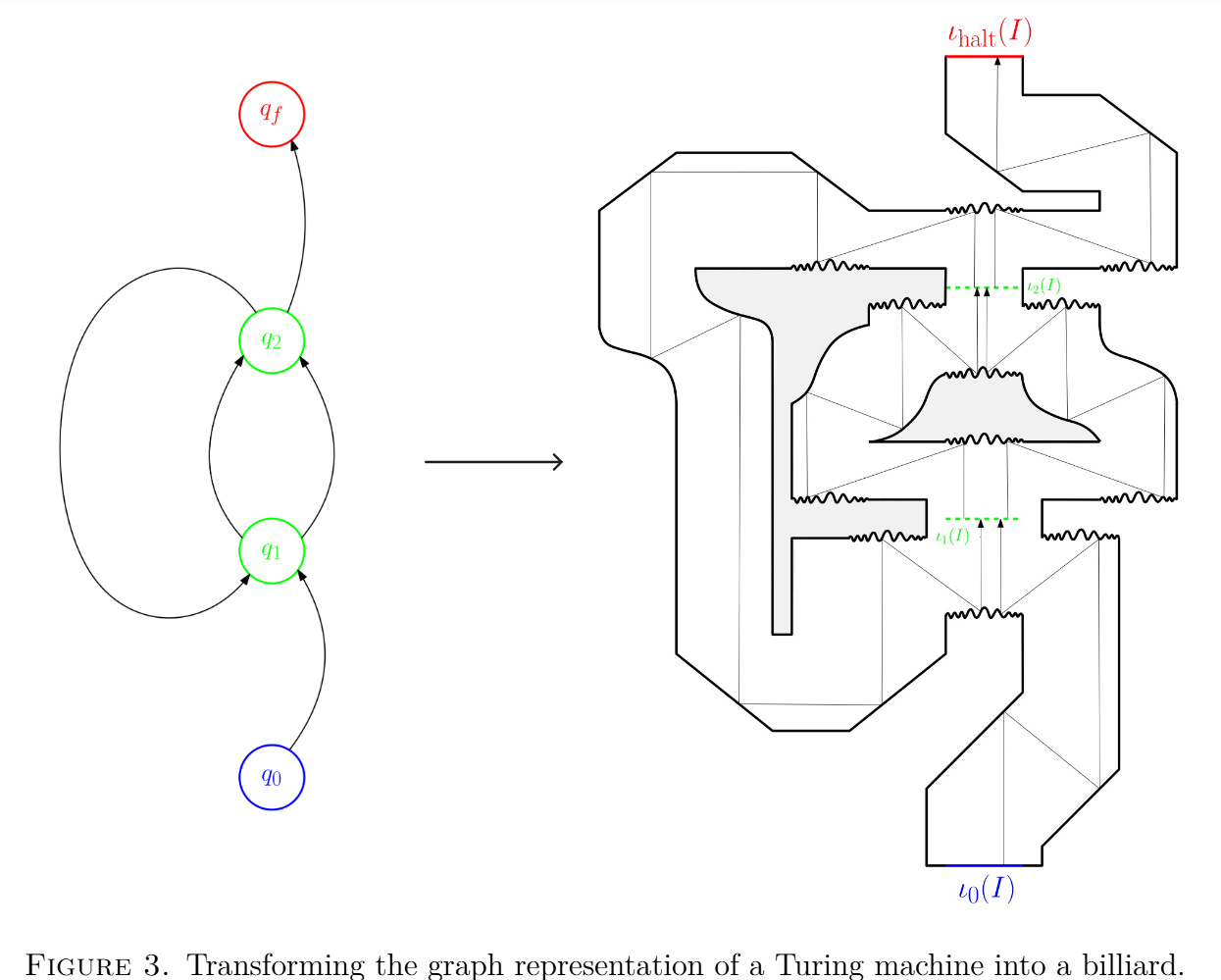

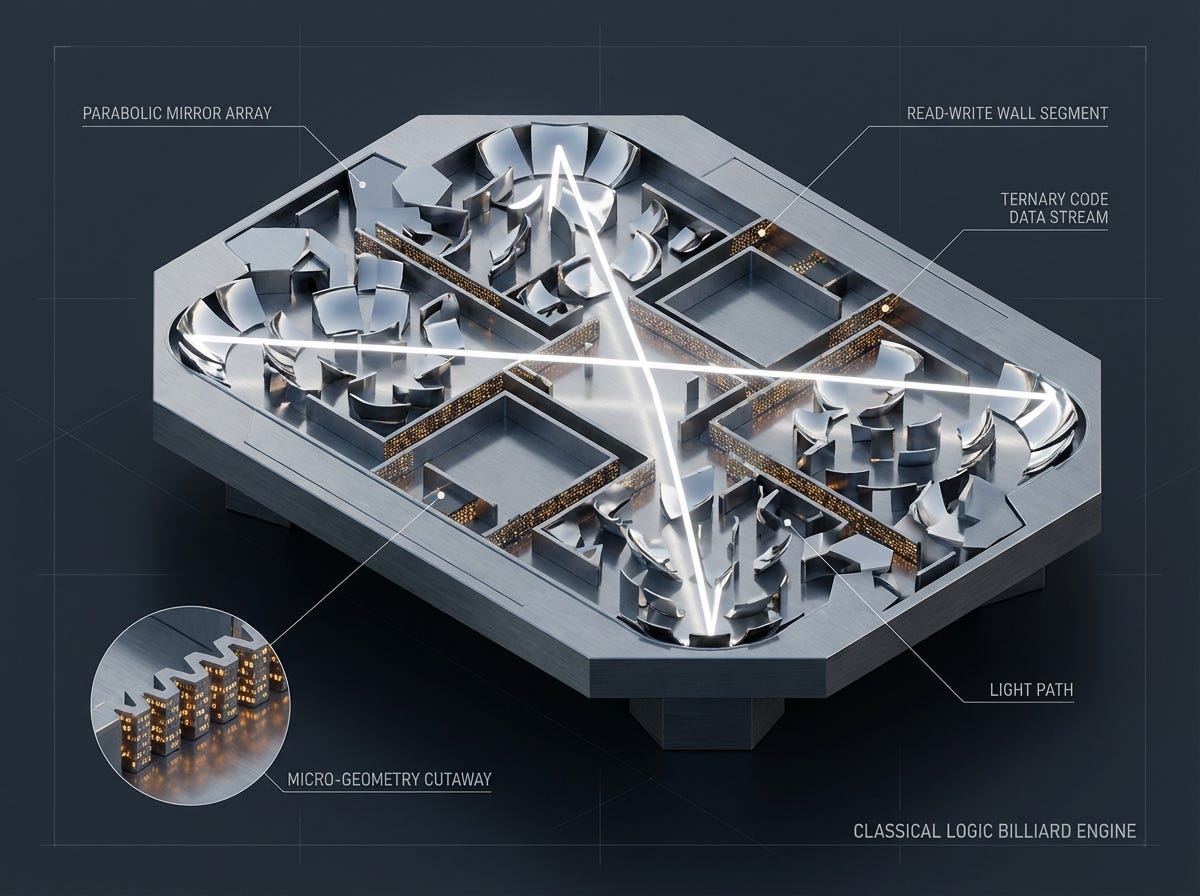

The core mechanism translates the logical operations of a Turing machine—Reading, Writing, and Shifting—into geometric optics. The authors visualize the Turing machine as a Finite State Machine graph, where nodes are internal states q and edges represent transitions. This graph is physically instantiated as a billiard table with non-trivial topology, as shown in Figure 3. Each edge in the graph becomes a “corridor” in the table.

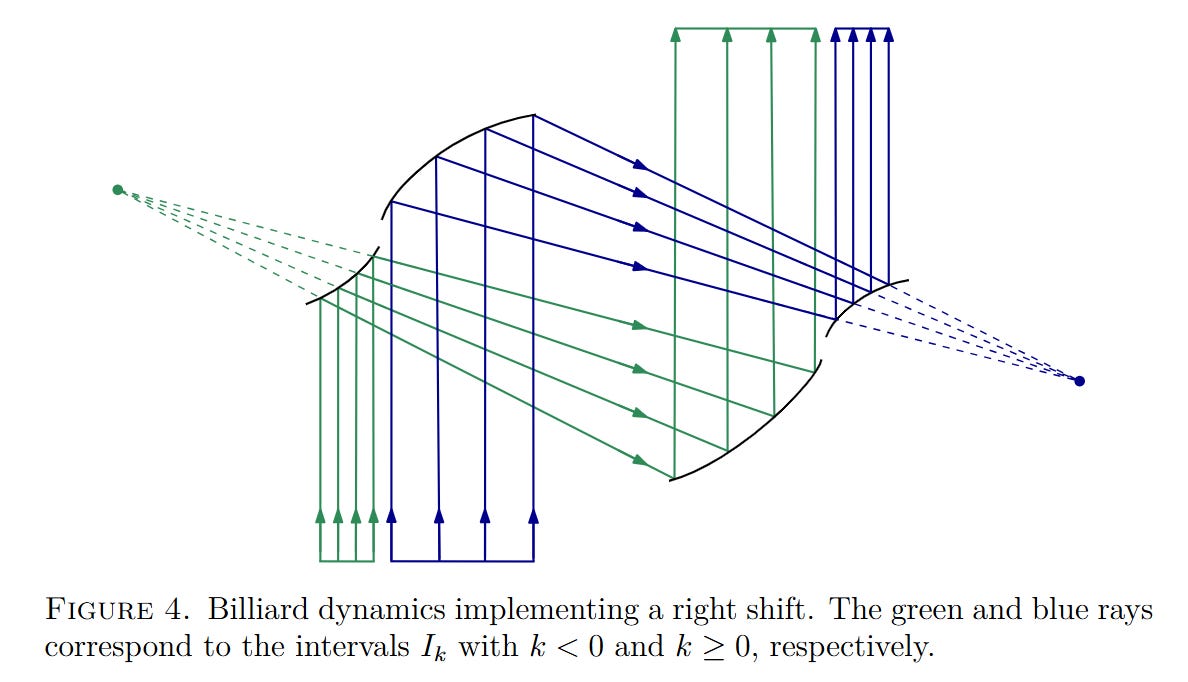

A ball entering a corridor represents the machine in a specific state. To execute a “Shift” operation (moving the head position k→k±1), the ball reflects off parabolic walls. These walls act as affine transformers; for example, a right shift is implemented by walls that scale the impact coordinate, effectively performing the arithmetic operation x↦3x (or similar affine variants) on the position coordinate. This utilizes the focusing properties of parabolas to exact the necessary multiplication in the ternary expansion.

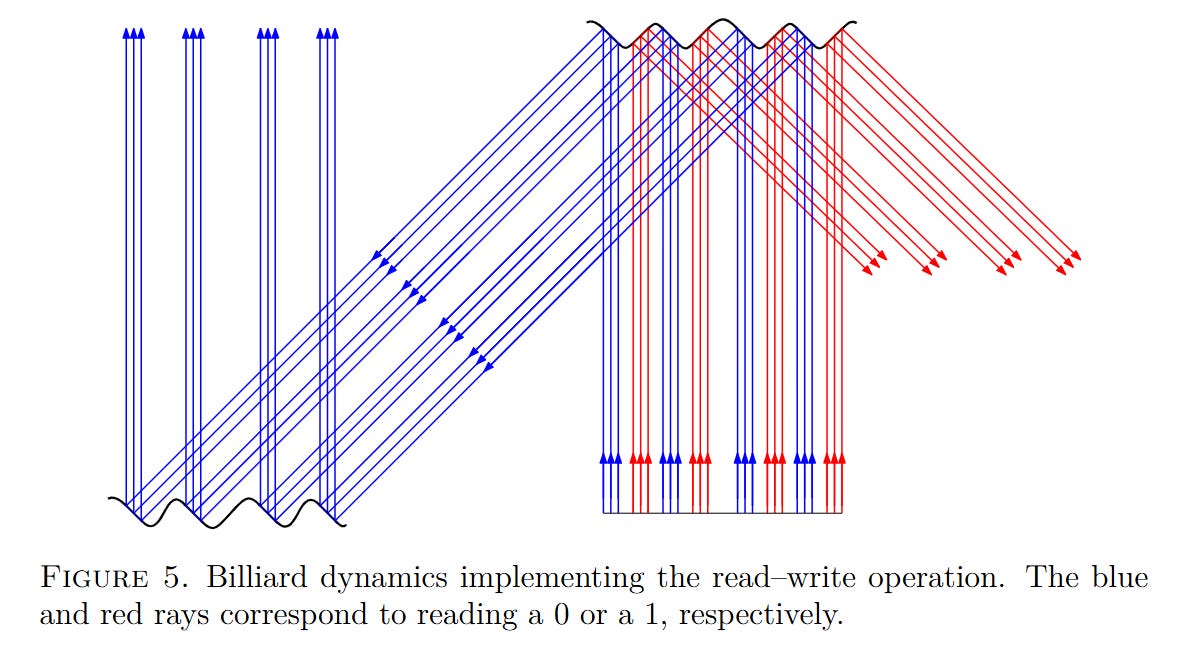

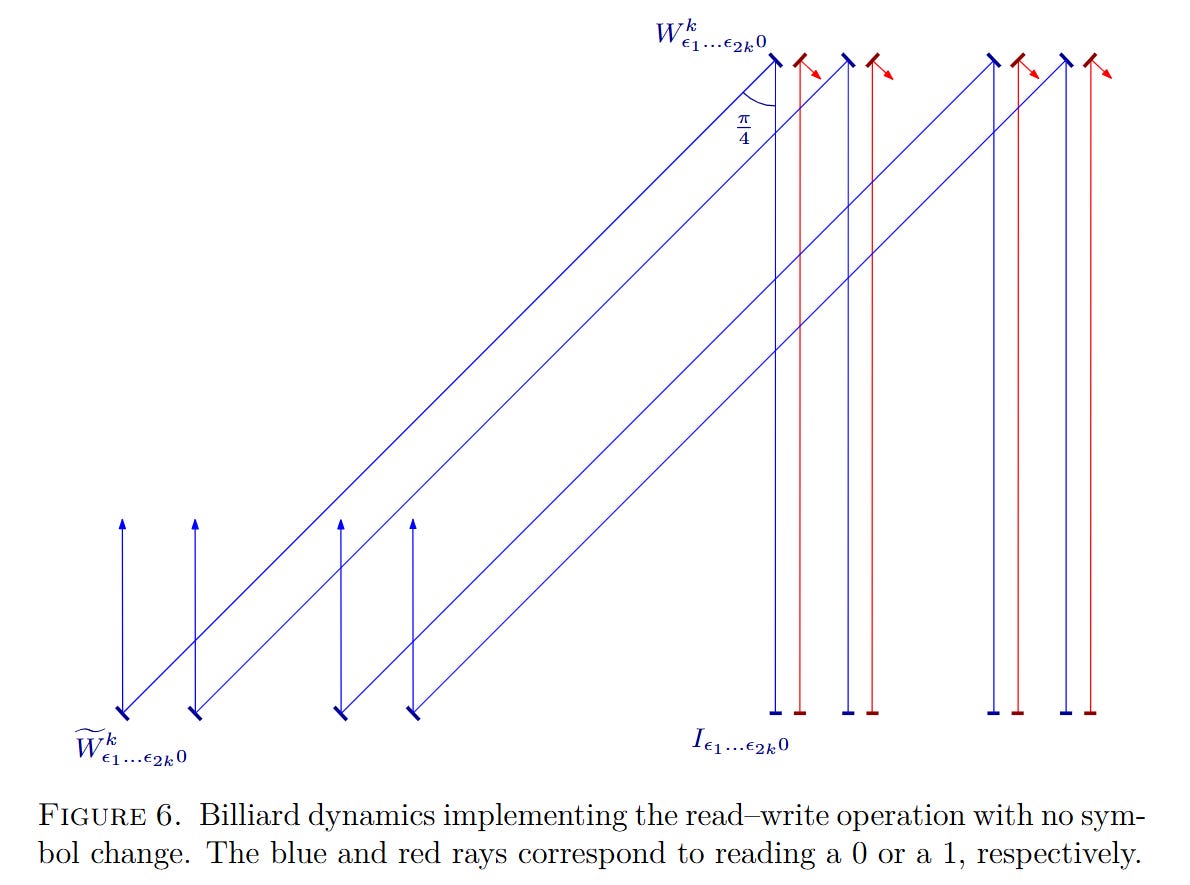

The “Read/Write” operation is significantly more complex. The system must mechanically distinguish whether the current digit is a 0 or a 1 and potentially flip it. The authors achieve this by exploiting the gaps in the Cantor set. As detailed in Figure 5 and Figure 6, the “Read” operation is implemented by a wall that is not a single smooth curve but a sequence of segments with alternating slopes. If the encoded bit is 0, the trajectory hits a segment with slope −1; if 1, it hits a slope of +1. These reflections diverge the trajectories into different subsequent corridors, effectively branching the physical path based on the logical bit.

Constructing the Logic Gates: The Micro-Geometry of Reflections

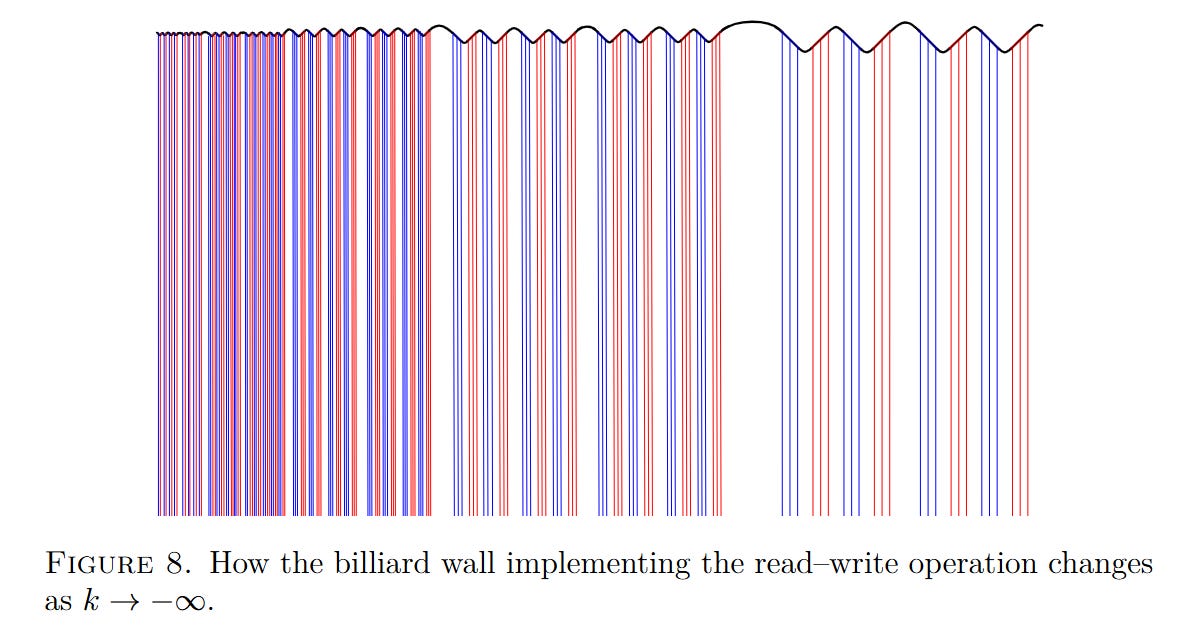

The engineering of the Read/Write walls requires careful attention to the fractal nature of the tape encoding. Because the head position k can be arbitrarily large, the “bit” to be read is located arbitrarily deep in the ternary expansion of the position xt,k. Consequently, the wall segments corresponding to these bits become infinitesimally small as k→∞.

The authors construct these walls as “zig-zag” curves where the number of oscillations grows as 22k and their amplitude shrinks as 3−(3k+2). As illustrated in Figure 8, the wall appears macroscopically smooth but contains the necessary microstructure to discriminate bits at any scale.

Crucially, the authors prove that these trajectories are robust enough to avoid unwanted collisions with other segments of the encoding. For the “Write” operation, the reflection angle is slightly perturbed to shift the trajectory horizontally by exactly the amount required to flip the bit in the ternary expansion. The authors define this angle αk precisely as: tanαk=1/(1+3−(3k+2)). This ensures the physical trajectory implements the symbolic update x→x±2⋅3−n without introducing errors.

Analysis: Undecidability as a Physical Observable

The validation of this system relies on the exact correspondence between the symbolic dynamics of the Turing machine and the symplectic map of the billiard. Because the authors utilize Reversible Turing Machines, the global transition function is injective, preventing the merging of trajectories and preserving the conservative nature of Hamiltonian dynamics.

The primary finding is that the Halting Problem for the embedded Turing machine maps directly to the reachability and periodicity problems in the billiard. Specifically, the authors prove that deciding whether a trajectory starting at a specific point ι0(xt,0) ever hits the “Halt” region of the boundary is equivalent to the Halting Problem. Furthermore, because the system is reversible, if the machine halts, the particle reflects orthogonally and retraces its path, creating a periodic orbit. Therefore, Corollary 2 establishes that deciding whether a trajectory is periodic is algorithmically undecidable. This suggests that in systems approximating these billiards—such as the N-body problem in celestial mechanics or hard-sphere gases—there exist configurations where the long-term qualitative behavior cannot be predicted by any algorithm, regardless of computational power.

The Precision Horizon and Topological Constraints

The construction faces limits regarding physical realizability, primarily due to the “Zeno” nature of the encoding. The wall segments for large k become smaller than the Planck length, and the initial condition requires defining a real number with infinite exact ternary digits. However, the authors argue that this specific construction remains more physically plausible than alternative encodings. They note that while previous theoretical attempts required physically impossible operations (like shifting the entire tape instantaneously), this method relies only on the focusing power of billiard dynamics to handle the complexity.

Additionally, the billiard table requires a non-trivial topology (holes/obstacles) to represent the cycles of the Finite State Machine graph. This means the result does not necessarily apply to strictly convex billiard tables (like an ellipse), but rather to polygonal tables with obstacles. The complexity of the table topology scales with the state complexity of the Turing machine being simulated.

Impact & Conclusion

“Classical Billiards Can Compute” serves as a rigorous confirmation that complexity is ubiquitous in classical dynamics. By extending the domain of TKFT to planar billiards, Miranda and Ramos have shown that undecidability stands alongside chaos as a twin pillar of unpredictability. While chaos prevents prediction due to measurement uncertainty (Lyapunov exponents), undecidability prevents prediction due to logical irreducibility.

This has profound implications for the foundations of physics. It suggests that even in purely deterministic, reversible, low-dimensional systems defined by simple reflection laws, there exist questions about the future state of the system that are mathematically unanswerable. For researchers in AI and dynamical systems, this reinforces the view that complex emergent behavior—and potentially general intelligence—does not require complex laws of physics, but can arise from the simplest interactions given sufficient time and memory.

The way this uses Cantor sets to encode the tape in phase space is genius—it's basically smuggling infinite discrete states into a continous geometry without breaking any physical laws. I remember trying to wrap my head around undecidability in undergrad and thinking it was just some abstract math thing, but seeing it emerge from something as simple as reflections off polygonal walls makes it feel way more fundamental. The bit about how this differs from chaos is huge: it's not just sensitivty to initial conditions, but a hard logical limit where no algoritm can predict long-term behavior.