Grounding Intelligence in Movement

Authors: Melanie Segado, Michael L. Platt, Felipe Parodi, Jordan K. Matelsky, Eva B. Dyer, Konrad P. Kording

Paper: https://arxiv.org/abs/2507.02771

Code: Not available

Model: Not available

TL;DR

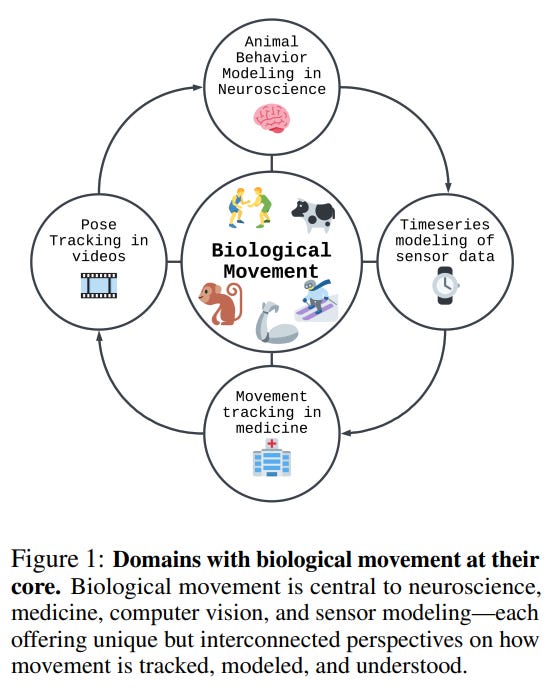

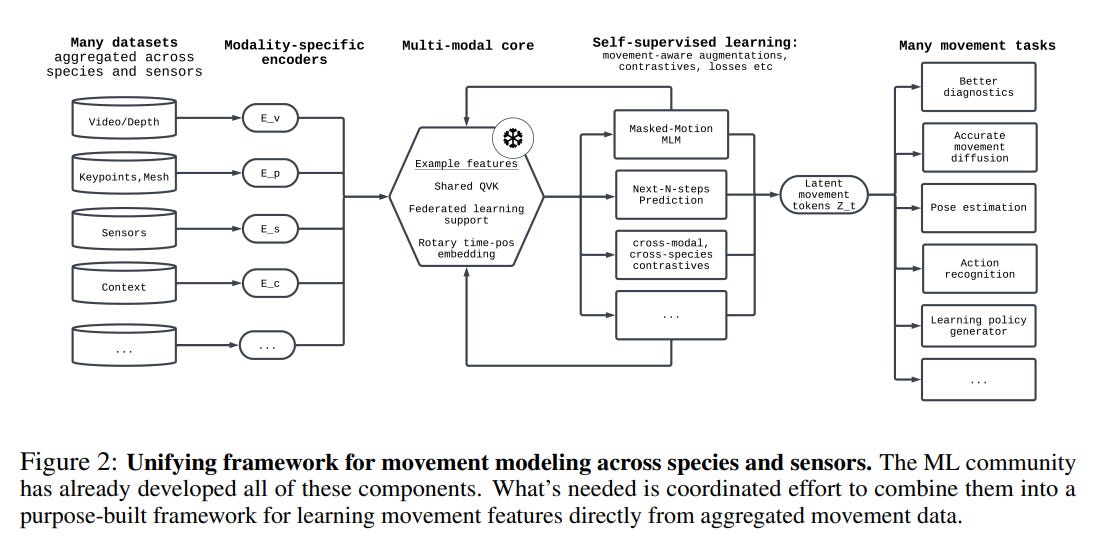

WHAT was done? The authors present a position paper arguing that biological movement should be treated as a primary, first-class modeling target for AI, rather than an afterthought of vision or language models. They critique the fragmented landscape of current approaches—from video generators that defy physics to reinforcement learning agents that fail to generalize—and propose a unifying framework to build overarching movement models. This framework (Figure 2) emphasizes cross-modal data integration (video, IMU, EMG, etc.), strict adherence to biomechanical and physical constraints, deep contextual awareness, and generalizability across diverse species and tasks.

WHY it matters? This work directly confronts a modern-day manifestation of Moravec's paradox: AI's persistent struggle with motor tasks that are trivial for most biological organisms. By advocating for a dedicated, foundational approach to movement, the paper charts a path to overcoming the limitations of current systems, which often lack physical plausibility and contextual understanding. Success in this area would not only advance core AI capabilities in generation and control but also create a shared foundation for understanding behavior across biological and artificial systems, unlocking transformative applications in robotics, medicine, neuroscience, and conservation.

Details

A New Frontier for Foundation Models

In recent years, AI has made staggering progress in domains like language and vision, yet a fundamental aspect of intelligence remains elusive: movement. While biological systems navigate the physical world with remarkable grace and adaptability, our most advanced AI models often fail spectacularly at depicting or executing even simple physical interactions. This paper, "Grounding Intelligence in Movement," presents a compelling argument that this gap exists because we have been treating movement as a secondary problem. The authors posit that it's time for a paradigm shift: movement should be treated as a primary modeling target for AI, deserving of its own foundational models.

The Problem: A Fragmented and Ungrounded Landscape

The paper begins by diagnosing the shortcomings of the current AI landscape. It highlights how state-of-the-art models, while impressive in their own domains, fall short when it comes to biological movement:

Generative Models: Video generators, despite their visual fidelity, often produce physically implausible results, such as "bodies floating up off the ground after a fall" or struggling to render a simple high-five. This failure stems from a lack of fundamental inductive biases for 3D kinematics and physics; they learn to paint plausible 2D scenes, not to simulate an embodied agent in a physical world.

Perception Models: Pose estimators and action recognizers can describe what a movement is but fail to capture the why—the underlying intent, the nuance of execution quality, or the critical context that gives the movement meaning. A model might recognize a handshake but cannot distinguish a voluntary greeting from a pathological tremor.

RL and World Models: Agents trained with reinforcement learning often learn brittle policies that fail to generalize across different contexts or species. An agent trained to emulate adult human walking will not understand an infant’s fidgeting without extensive, from-scratch retraining, revealing a lack of foundational movement intelligence.

This fragmentation means that progress is siloed, and a truly generalizable understanding of movement remains out of reach.

Why Not Just Scale Existing Models?

The authors proactively address the most likely counter-argument: that progress will emerge naturally from scaling existing, specialized models. They contend that simply scaling video generators or world models is insufficient because these approaches, even at massive sizes, will struggle with physical realism, interpretability, and cross-species generalization unless intentionally designed with curated constraints and biomechanical data.

This also distinguishes their proposal from earlier "generalist" agents like Gato (https://arxiv.org/abs/2205.06175). While such agents were trained on disparate tasks with little shared structure, the authors argue that all movement tasks—from an infant's fidgeting to a primate's locomotion—belong to a single, coherent domain governed by shared principles of physics and biology. This coherence is precisely why a foundational movement model is poised to succeed, allowing for meaningful knowledge transfer between seemingly different actions.

A Unifying Framework and Roadmap

To address these challenges, the authors propose an intentional, coordinated effort to build overarching models of movement. Their proposed framework (Figure 2) is built on four key principles: cross-modal integration, physical grounding, context-awareness, and generalizability.

They outline a clear, three-step roadmap for the AI community to realize this vision:

Aggregate a Movement "Data Pile": The first step is to collect and, crucially, standardize the vast and varied movement data that already exists. This involves aggregating everything from high-fidelity motion capture datasets like AMASS and web-scraped video collections like Motion-X to rich sensor logs from wearables, as seen in the CAPTURE-24 dataset. This requires creating data conventions (akin to the BIDS format in neuroimaging (https://joss.theoj.org/papers/10.21105/joss.01896)) and curating datasets with rich, multi-modal context.

Pretrain a Multimodal Backbone: A flexible, general-purpose backbone should be pretrained on this data pile. The authors propose several key innovations here, such as developing movement-aware data augmentations (that don't erase diagnostic signals like tremors) and leveraging federated learning to train on sensitive medical data without compromising privacy.

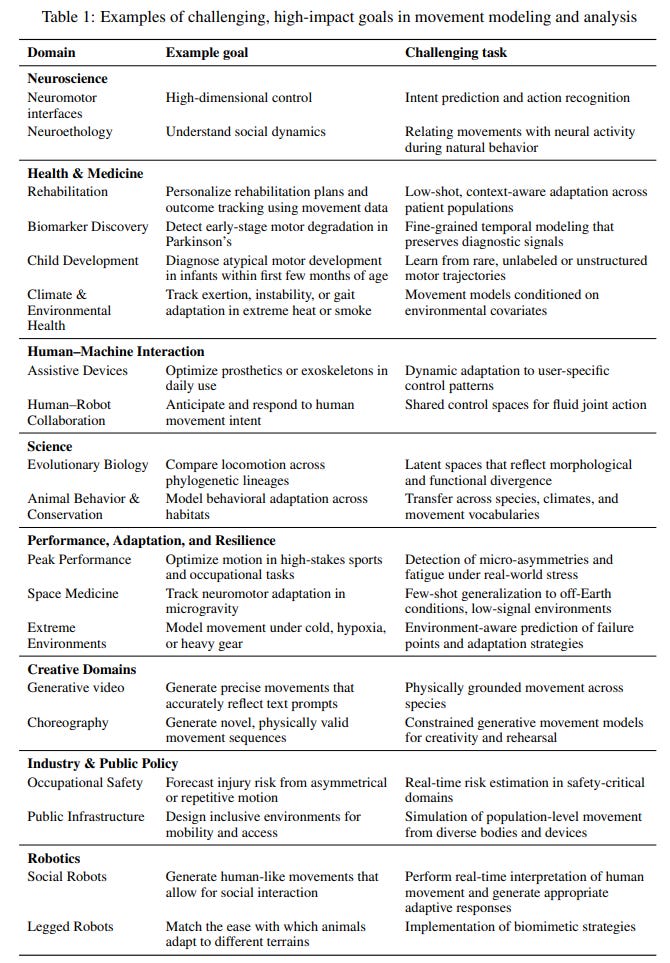

Evaluate on High-Impact Use Cases: Success should be measured by practical utility. The paper advocates for new, outcome-aligned benchmarks that test for causal understanding, cross-domain generalization, and diagnostic significance, providing a comprehensive list of examples of these high-impact goals (Table 1).

The Path Forward

"Grounding Intelligence in Movement" is more than a survey; it is a powerful call to action. It challenges the prevailing assumption that a deep understanding of movement will simply emerge from scaling existing models. Instead, it argues that movement intelligence requires a dedicated, intentional, and physically-grounded approach.

The authors are realistic about the challenges, highlighting the immense difficulty of data aggregation and the need for deep domain expertise. They also dedicate significant attention to the ethical risks, such as biometric privacy and algorithmic bias, advocating for a responsible AI approach from the outset.

By framing movement as a core pillar of intelligence, this work opens up a research agenda with profound implications. Developing models that truly understand movement would not only produce more capable robots and more insightful scientific tools but would also push us toward a deeper understanding of intelligence itself—not as an abstract computational process, but as something fundamentally grounded in physical interaction, goal-directed behavior, and adaptation to a dynamic world. This paper provides a compelling and well-articulated vision for how to get there.