[NeurIPS 2025] Does Reinforcement Learning Really Incentivize Reasoning Capacity in LLMs Beyond the Base Model?

NeurIPS 2025 Best Paper Runner-Up Awards

Authors: Yang Yue, Zhiqi Chen, Rui Lu, Andrew Zhao, Zhaokai Wang, Yang Yue, Shiji Song, Gao Huang

Paper: https://arxiv.org/abs/2504.13837, NeurIPS submission

Code: https://limit-of-rlvr.github.io

TL;DR

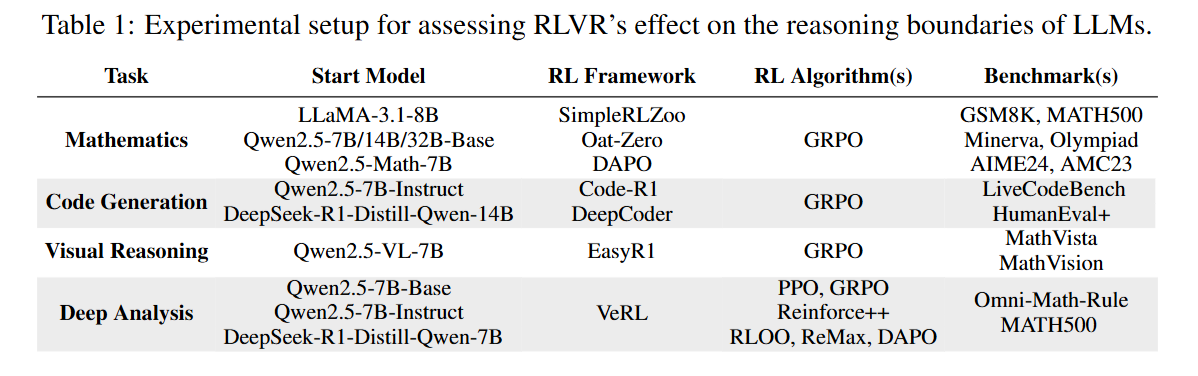

WHAT was done? In this NeurIPS 2025 Best Paper Runner-Up, the authors systematically probed the reasoning boundaries of Large Language Models (LLMs) trained via Reinforcement Learning with Verifiable Rewards (RLVR). Using the unbiased pass@k metric across mathematics, coding, and visual reasoning tasks, they compared base models against their RL-tuned counterparts to determine if RLVR generates novel reasoning patterns or merely amplifies existing ones.

WHY it matters? The findings challenge the prevailing narrative that RLVR allows models to autonomously discover “superhuman” strategies similar to AlphaGo. The study reveals that while RLVR significantly improves sampling efficiency (correct answers appear more often), it does not expand the model’s fundamental reasoning capability boundary. In fact, for large k, base models often solve more unique problems than their RL-trained versions, suggesting that current RL methods are bounded by the priors of the pre-trained model.

Details

The Capability Bottleneck: Exploration vs. Exploitation

The current zeitgeist in post-training suggests that Reinforcement Learning with Verifiable Rewards (RLVR) serves as a catalyst for “System 2” thinking, enabling models to self-correct, backtrack, and discover novel solution paths that were absent in the base model. This assumption draws a parallel to the “AlphaGo moment,” where an agent transcends human heuristics through self-play. However, this paper posits a critical conflict: does the reported performance gain in models like DeepSeek-R1 or OpenAI-o1 stem from learning new reasoning behaviors, or simply from suppressing the probability of incorrect tokens in favor of correct paths that already existed in the latent distribution? By shifting the evaluation focus from average accuracy (greedy or low-temperature sampling) to the theoretical maximum coverage of the model’s distribution, the authors aim to decouple sampling efficiency from genuine capability expansion.

Methodological First Principles: Pass@k as a Boundary Probe

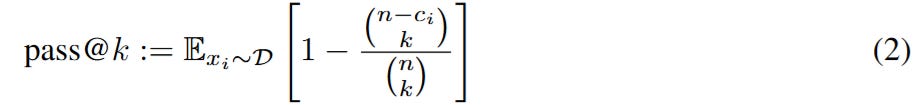

To rigorously define “capability,” the authors move beyond standard accuracy metrics and utilize the pass@k estimator. In this context, the atomic unit of analysis is the set of potential reasoning traces y a model πθ can generate for a prompt x. The metric pass@k represents the probability that at least one correct solution exists within k independent samples. The authors employ the unbiased estimator for a finite budget of n samples where c is the count of correct solutions:

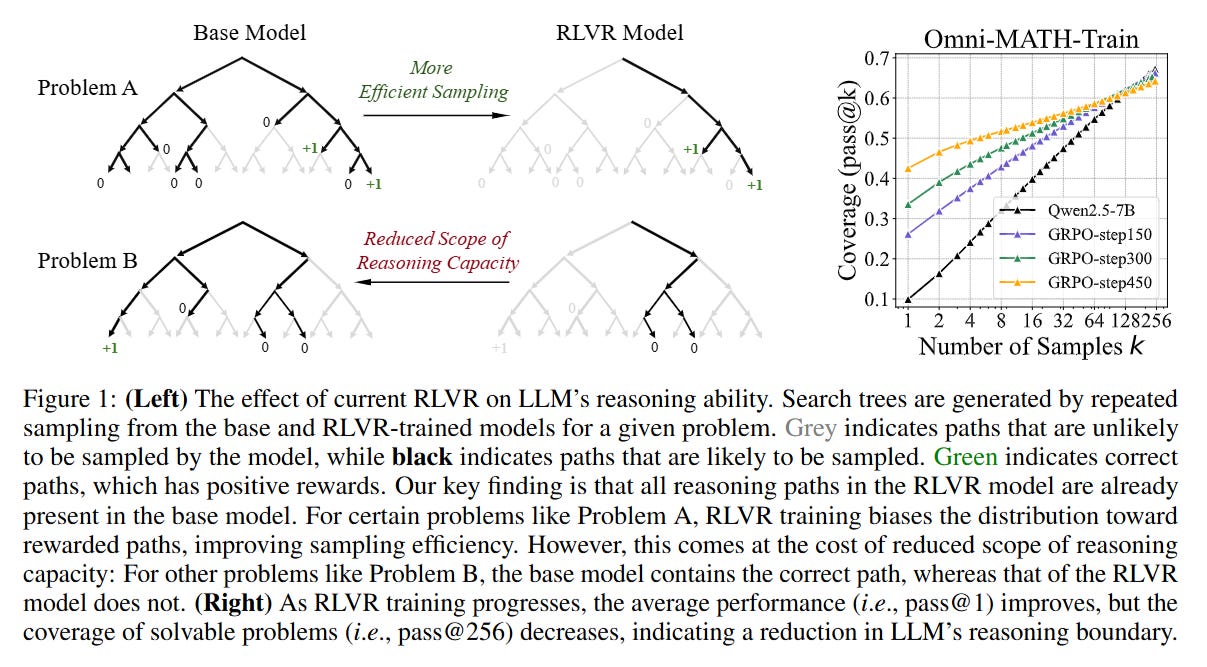

This formulation is crucial because it serves as a proxy for the model’s total reasoning surface area. If RLVR truly teaches the model new strategies (e.g., a novel way to decompose a geometry problem), the pass@k curve at high k (e.g., k=256 or 1024) should increase relative to the base model. Conversely, if RLVR acts merely as a rejection sampler that sharpens the probability density around known correct paths, the asymptotic performance at large k would remain static or even degrade due to entropy collapse.

The Probability Shift: Sharpening the Distribution

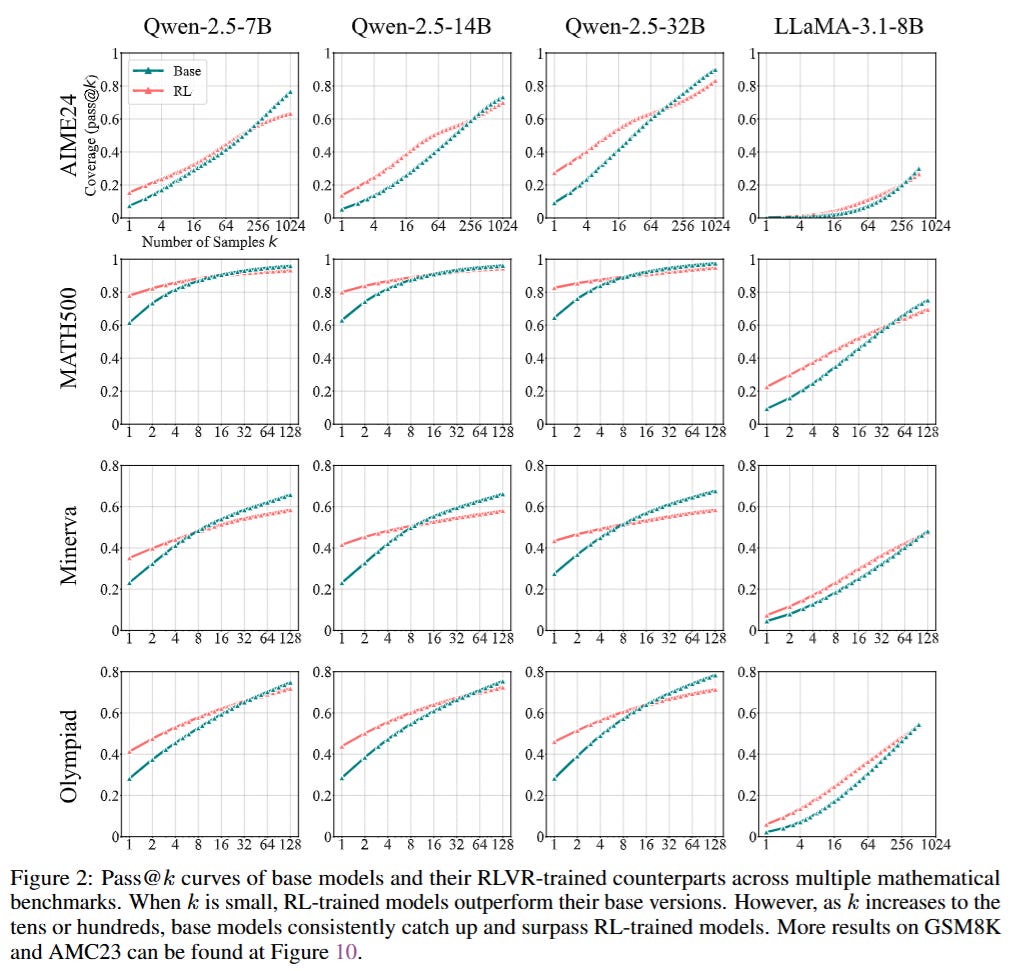

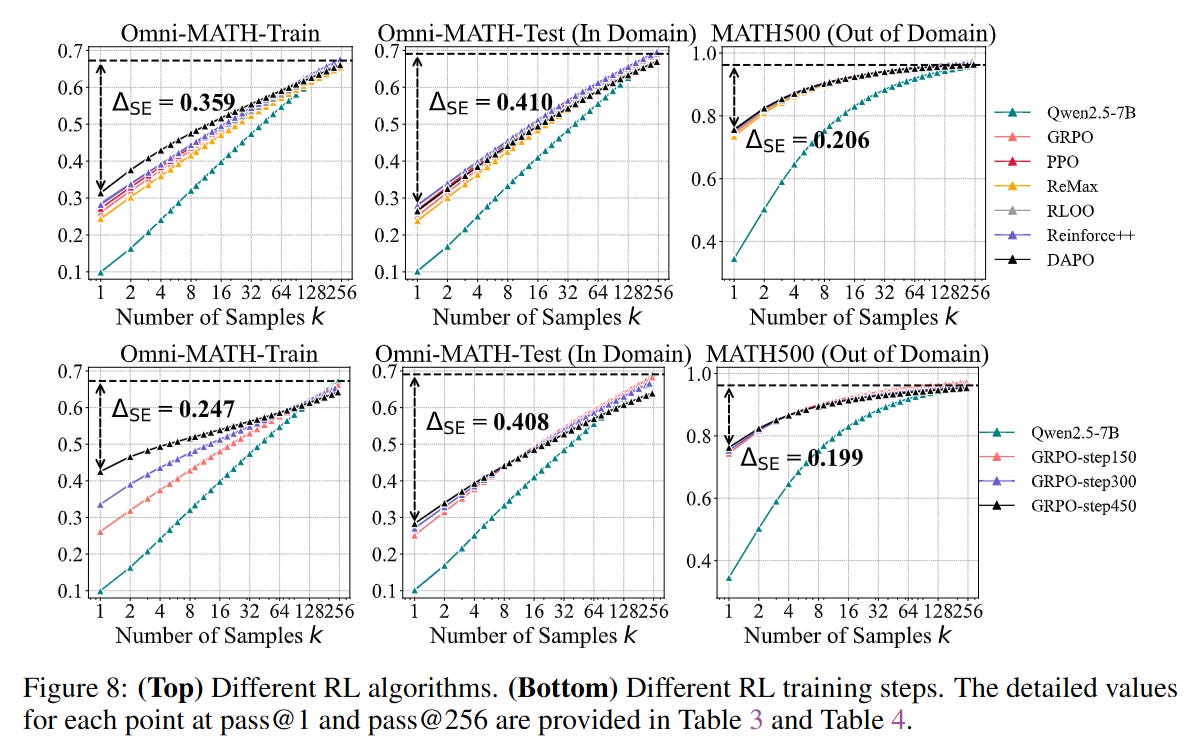

The core mechanism reveals a startling inversion of expectations. When analyzing performance on benchmarks like AIME24 and MATH500, the authors observe that while RL-trained models dominate at k=1 (average case), the Base Models consistently overtake them as k increases. This phenomenon, visualized in Figure 2, indicates that the set of problems solvable by the RL model is effectively a subset of those solvable by the Base model.

Consider a specific input example from the AIME dataset: the Base model might assign a very low probability (e.g., 10−4) to the correct chain-of-thought (CoT) path, making it invisible during greedy decoding. The RLVR process, optimizing the reward r∈{0,1}, dramatically increases the likelihood of this specific path. However, in doing so, the RL model sacrifices diversity.

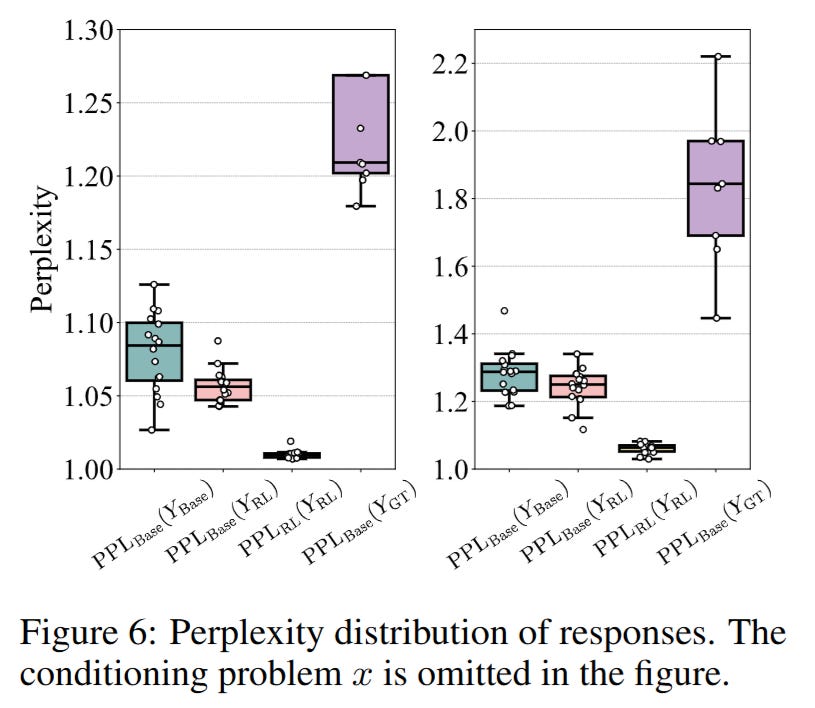

The authors confirm this via perplexity analysis (Figure 6), showing that the “reasoning paths” generated by RL models are already present and highly probable within the Base model’s distribution. The RL training does not synthesize fundamentally new logical bridges; it merely re-weights the existing graph of token transitions to favor those that lead to verifiable rewards.

Algorithm Invariance and Implementation Details

A significant portion of the study is dedicated to ensuring these results are not artifacts of a specific algorithm. The authors re-implemented a suite of RLVR algorithms including PPO (Proximal Policy Optimization), GRPO (Group Relative Policy Optimization), Reinforce++, and ReMax. The training setup utilized the AdamW optimizer with a constant learning rate of 10−6 and excluded the KL-divergence penalty in certain runs (like Oat-Zero and DAPO) to allow maximum exploration.

Despite these variations, the Sampling Efficiency Gap (ΔSE)—defined as the difference between the RL model’s pass@1 and the Base model’s pass@k—remained stubbornly high across all algorithms (Figure 8).

This suggests that the limitation is not a flaw in PPO or GRPO, but a fundamental property of applying on-policy RL to a frozen pre-training prior without environmental interaction that provides new information.

Analysis: The “Subset” Phenomenon vs. Distillation

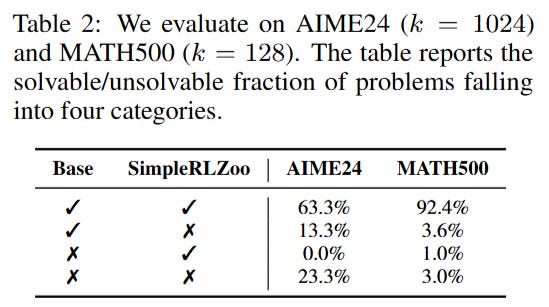

The validation of these claims is bolstered by granular coverage analysis. On the AIME24 benchmark, the authors categorized problems based on whether they were solvable by the Base model, the RL model, or both. As detailed in Table 2, there was a negligible number of problems that only the RL model could solve (0.0%), whereas a significant chunk (13.3%) could only be solved by the Base model given sufficient sampling (k=1024).

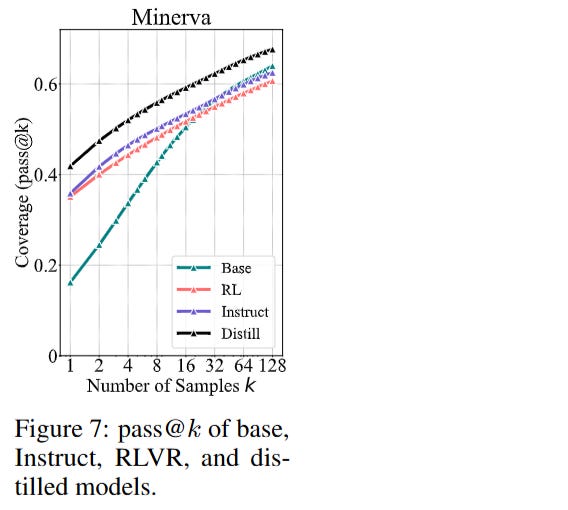

Furthermore, the authors contrasted this with Distillation. Unlike RLVR, which is self-contained, distillation involves training a student model on traces from a superior teacher (e.g., DeepSeek-R1). In this setting, the student’s reasoning boundary did expand, surpassing the base model’s original capacity (Figure 7). This acts as a control experiment, proving that the architecture can learn new reasoning patterns, but self-play RLVR is insufficient to generate them solely from the base model’s priors.

Limitations

While the study provides a compelling counter-narrative, it is bounded by the magnitude of k. It is theoretically possible that “new” strategies exist at astronomically low probabilities (k→∞) in the base model, which RL might locate. The study is also limited to single-turn reasoning tasks (Math/Code) where verifiable rewards are binary. The dynamics might differ in multi-turn environments or open-ended creative tasks where the reward landscape is dense and gradient-rich. Additionally, the analysis relies heavily on open-weights models (Qwen, LLaMA); while they validated trends on Mistral, the internal dynamics of closed frontiers (like the latest iterations of o1) remain a black box.

Impact & Conclusion

This paper forces a recalibration of the “Self-Improvement” narrative. It suggests that current RLVR techniques are best understood as inference-time optimization baked into weights, rather than a discovery engine for novel intelligence. The base model serves as a hard upper bound on reasoning capability. To truly advance beyond the base model, the authors argue we must move beyond simple verifiers and towards continual pre-training, multi-turn agentic interaction, or richer exploration strategies that can break the gravitational pull of the pre-trained prior. For researchers at the frontier, this underscores that “scaling compute during training” via RL requires better data or environments, not just more PPO steps on the same prompt distribution.