[NeurIPS 2025] Superposition Yields Robust Neural Scaling

NeurIPS 2025 Best Paper Runner-Up Awards

Today is the last (but not least) of the best and runner-up NeurIPS 2025 paper awards.

Authors: Yizhou Liu, Ziming Liu, and Jeff Gore

Paper: https://arxiv.org/abs/2505.10465, NeurIPS submission

Code: https://github.com/liuyz0/SuperpositionScaling

TL;DR

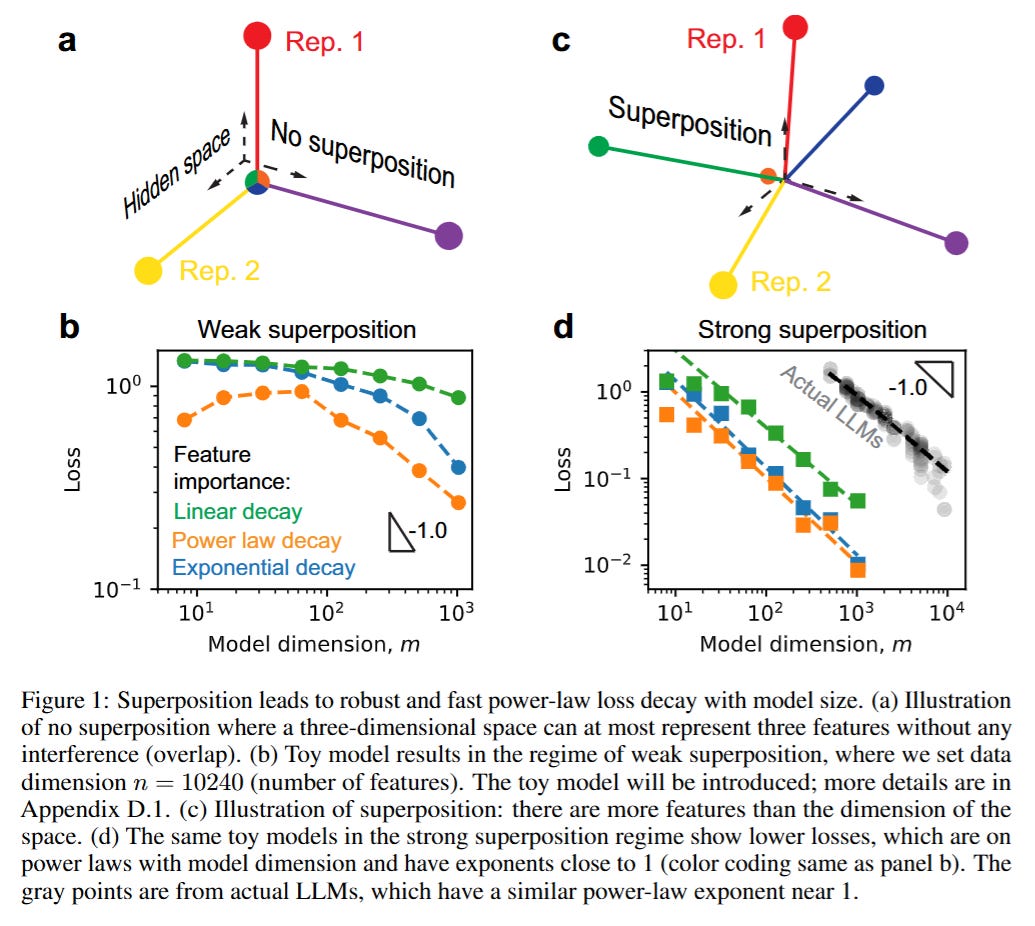

WHAT was done? The authors propose a mechanistic explanation for neural scaling laws by linking them to representation superposition. By adapting a sparse autoencoder framework and validating on open-source LLMs (OPT, Pythia, Qwen), they demonstrate that when models operate in a “strong superposition” regime—representing significantly more features than they have dimensions—the loss scales inversely with model width (L∝1/m). This scaling is driven by the geometric interference between feature vectors rather than the statistical properties of the data tail.

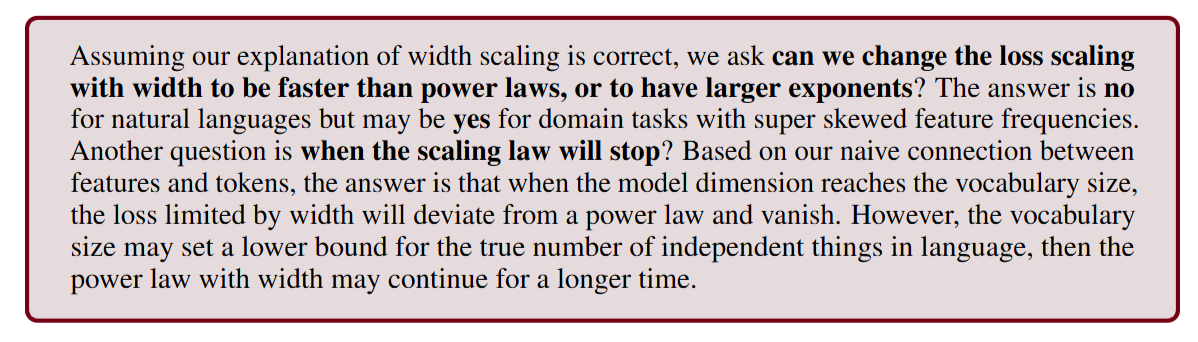

WHY it matters? This work, a NeurIPS 2025 Best Paper Runner-Up, provides a first-principles derivation of scaling laws that is robust to data distribution. Unlike previous theories relying on manifold approximation, this research suggests that the “power law” behavior of LLMs is a geometric inevitability of compressing sparse concepts into dense spaces. It implies that overcoming these scaling barriers requires architectural interventions to manage feature interference, as simply adding more data cannot bypass the geometric bottleneck.

Details

The Mechanistic Gap in Neural Scaling

The empirical validity of neural scaling laws—where loss decreases as a power law with model size, data, and compute—is the foundation of modern LLM development, exemplified by the Chinchilla scaling laws. However, the theoretical origin of these laws remains unresolved. Previous mechanistic explanations have largely focused on the resolution-limited regime, where the model attempts to approximate a smooth data manifold. In these frameworks, the scaling exponent α in L∝m−α is predicted to be highly sensitive to the spectral decay of the data distribution. This creates a conflict with empirical reality, where LLM scaling laws appear universally robust across diverse datasets and architectures. The authors address this gap by shifting the focus from manifold approximation to representation learning, investigating how limited width constrains the storage of sparse features.

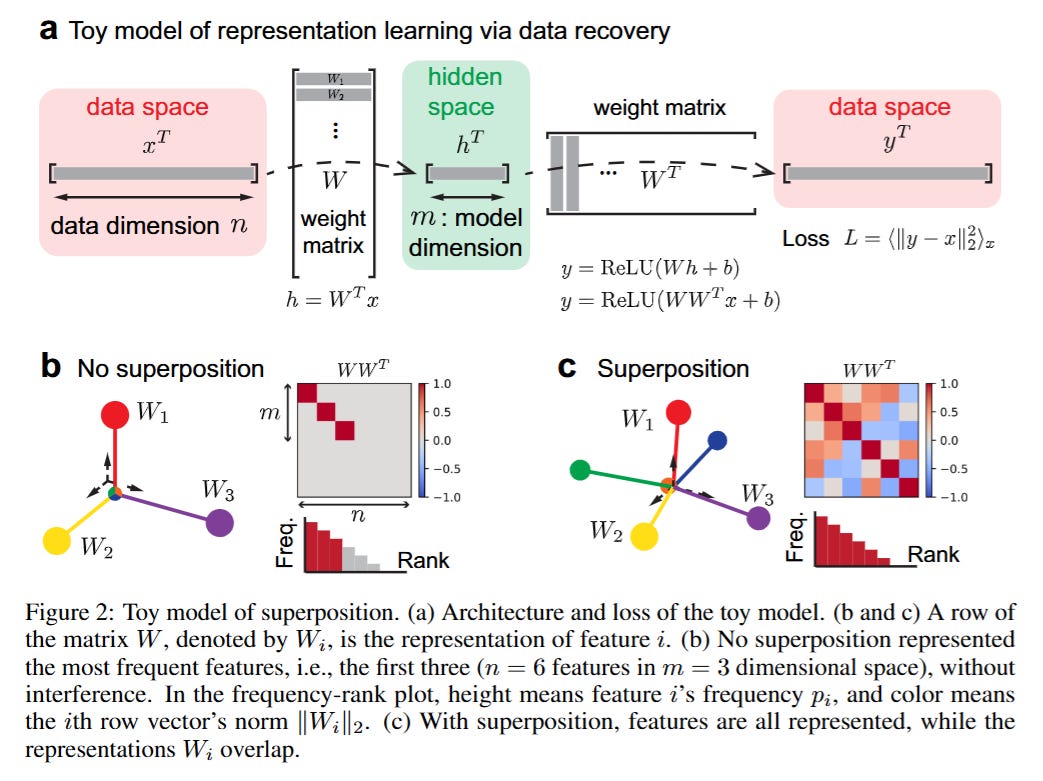

Superposition First Principles: The Toy Model Setup

To isolate the mechanics of scaling, the authors adapt the Toy Models of Superposition framework popularized by Anthropic. The core theoretical object is the feature vector x∈Rn, which is sparse. The model projects this high-dimensional input into a lower-dimensional hidden state h∈Rm (where m≪n) via a weight matrix W, attempting to recover it. The input features are modeled as xi=uivi, where ui determines sparsity and vi determines magnitude. The critical tension arises from the bottleneck: the model must compress n potential features into m dimensions.

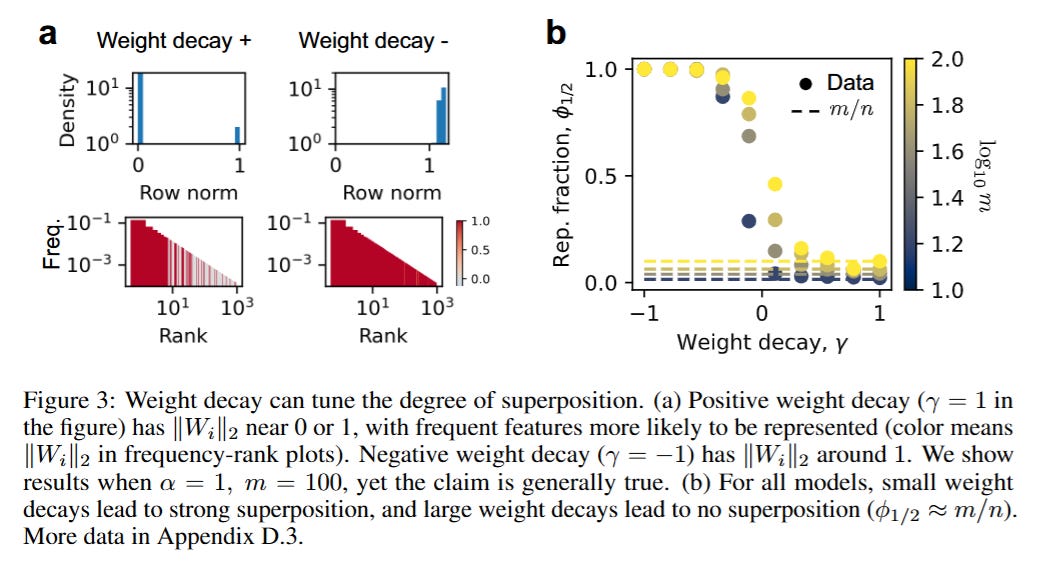

The authors distinguish between two distinct regimes governed by the weight decay parameter γ. In the Weak Superposition regime, the model acts as a filter, storing only the top m most frequent features orthogonally and ignoring the rest. In the Strong Superposition regime—which the authors argue is where real LLMs operate—the model attempts to store all features by allowing their representation vectors Wi to be non-orthogonal. The loss function, defined as the reconstruction error L=⟨∥y−x∥22⟩x, becomes a function of the interference between these overlapping vectors.

From Feature Sparsity to Geometric Interference

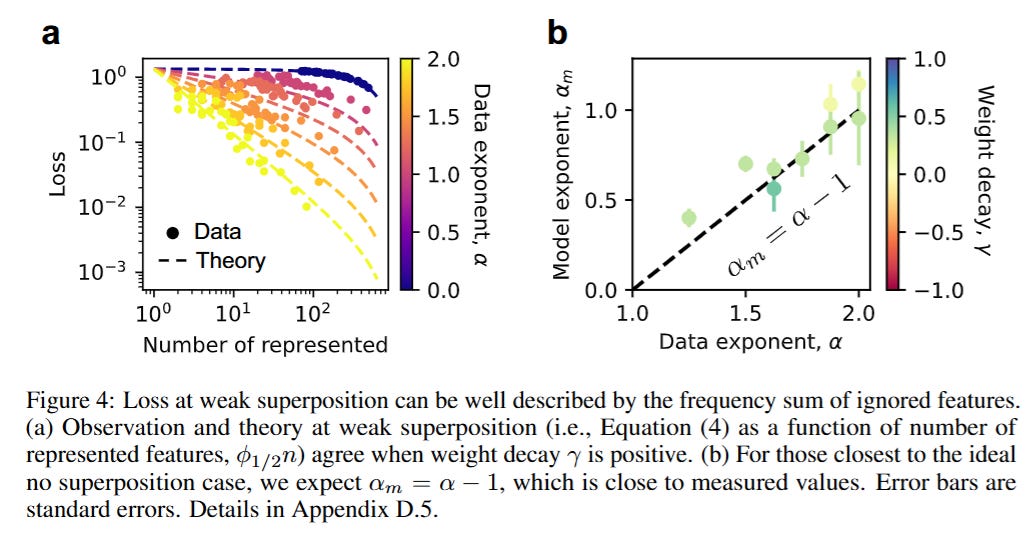

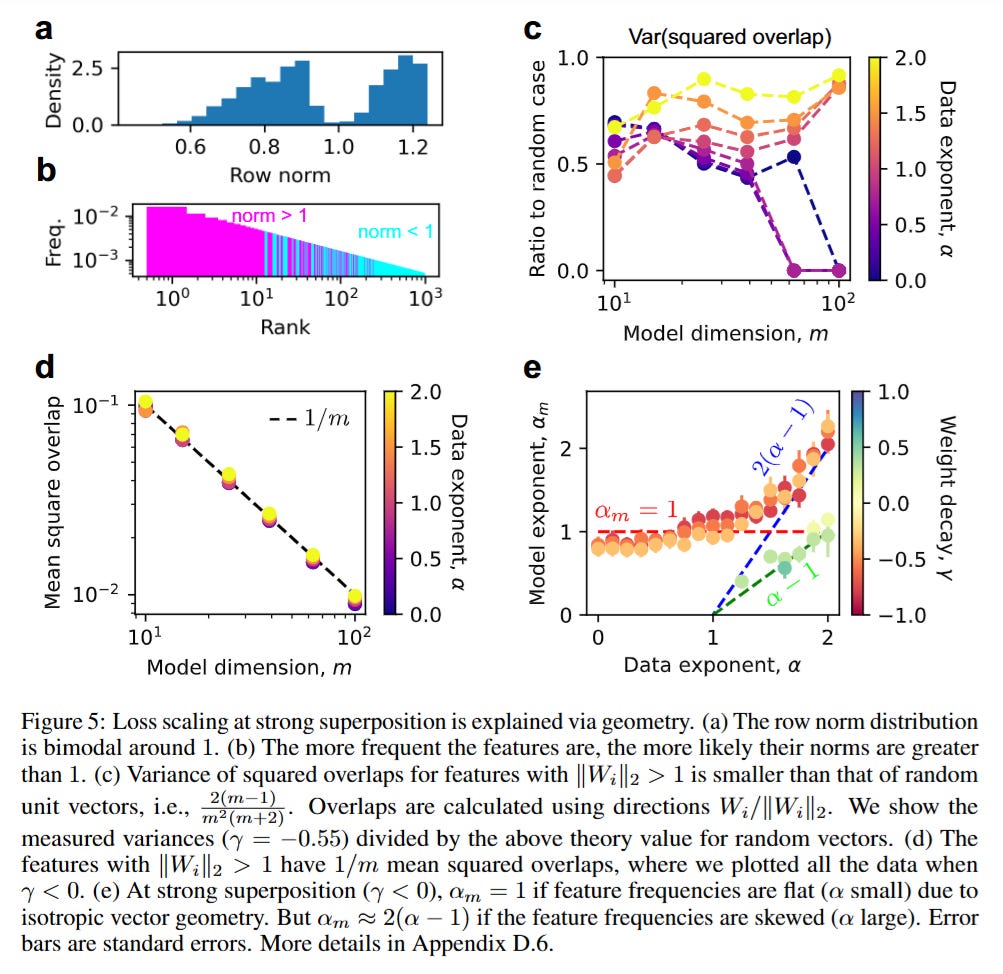

The transition between these regimes fundamentally alters the scaling behavior. As illustrated in Figure 4, when the model is in weak superposition, the loss is dominated by the summed frequency of the unrepresented features. Consequently, the scaling law depends entirely on the data distribution; if feature frequencies decay as pi∝1/iα, the loss scales as L∝m−(α−1). This regime is fragile and data-dependent.

However, the authors demonstrate a phase transition into Strong Superposition when weight decay is reduced. Here, the model learns an overcomplete basis. The researchers show that the representation vectors tend to arrange themselves into an Equiangular Tight Frame (ETF) or an ETF-like structure, maximizing the angle between vectors to minimize interference. In this regime, the squared overlap between any two feature vectors scales inversely with the dimension, roughly following ⟨(Wi⋅Wj)2⟩∝1/m. Because the reconstruction error in the toy model is driven by these interference terms, the loss becomes robustly proportional to 1/m, or L∝m−1. This leads to the critical insight shown in Figure 5: in strong superposition, the scaling law becomes “universal” and largely independent of the specific skewness of the data distribution.

Validation: Do LLMs Obey the Geometry?

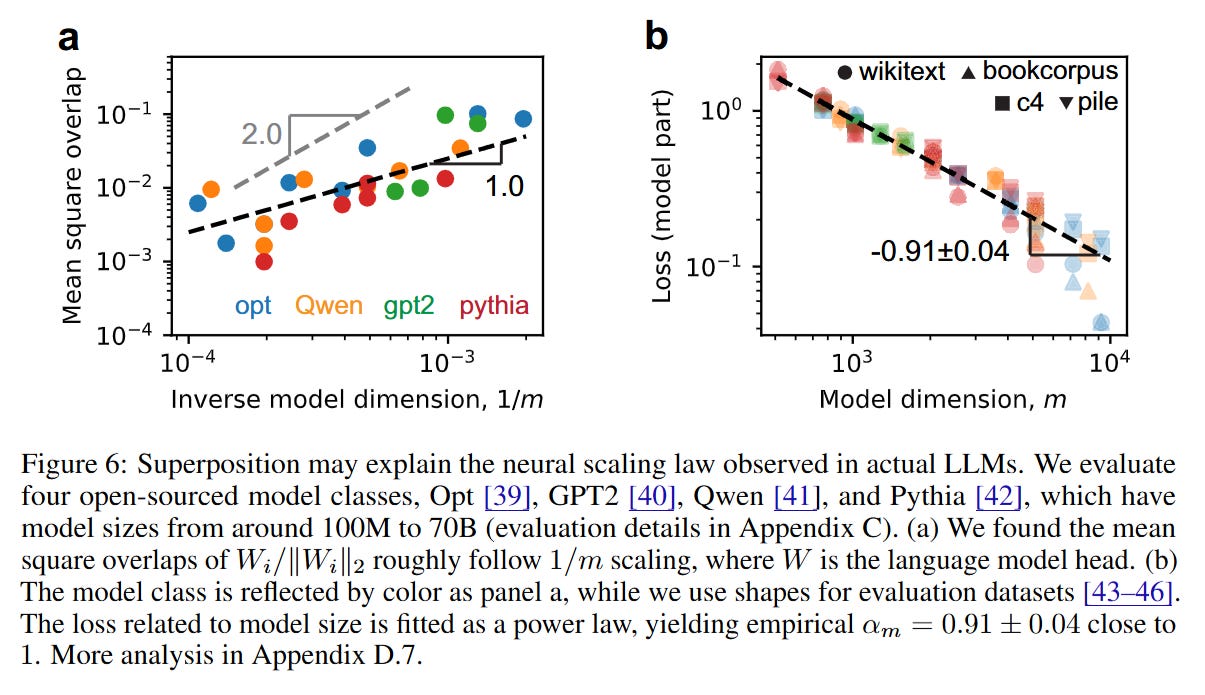

A major contribution of this work is bridging the gap between the toy model and production-grade LLMs. The authors analyzed the language model heads of several open-source families, including OPT, GPT-2, Pythia, and Qwen, with parameter counts ranging from 100M to 70B. They treat the vocabulary tokens as the atomic features (n) and the model width as the dimension (m).

The empirical results strongly support the strong superposition hypothesis. As shown in Figure 6, the representation vectors in real LLMs are not orthogonal; instead, their mean squared overlaps scale remarkably close to the predicted 1/m relationship.

Furthermore, when fitting the loss of these models against their width, the authors extract an empirical exponent αm≈0.91±0.04, which is strikingly close to the theoretical prediction of 1.0 derived from the geometry of strong superposition. This suggests that modern LLMs are indeed operating in a regime where performance is limited by the geometric interference of packing too many token representations into a fixed-width vector space.

Limitations and Strategic Implications

While the geometric intuition is compelling, the authors note several limitations. The toy model relies on Mean Squared Error (MSE), whereas LLMs are trained with Cross-Entropy. The paper provides a Taylor expansion argument suggesting that Cross-Entropy behaves similarly to MSE for small overlaps, but this remains an approximation. Additionally, assuming “tokens” are the atomic, independent features of language is a necessary simplification; in reality, language contains higher-order semantic features with complex sparsity patterns.

For system architects, this research implies that the widely observed neural scaling laws are not merely a result of statistical learning on power-law data, but a geometric necessity of distributed representations. If L∝1/m is driven by the limits of packing vectors in Euclidean space, then simply adding more data without increasing width faces a hard “interference floor.” The finding that LLMs naturally gravitate toward strong superposition suggests that training stability techniques should be explicitly tuned to maintain this regime, maximizing the efficiency of feature storage within the available model dimension.