[NeurIPS 2025] Why Diffusion Models Don’t Memorize: The Role of Implicit Dynamical Regularization in Training

NeurIPS 2025 Best Paper Award

Authors: Tony Bonnaire, Raphaël Urfin, Giulio Biroli, Marc Mézard

Paper: https://arxiv.org/abs/2505.17638, NeurIPS submission

Code: https://github.com/tbonnair/Why-Diffusion-Models-Don-t-Memorize

TL;DR

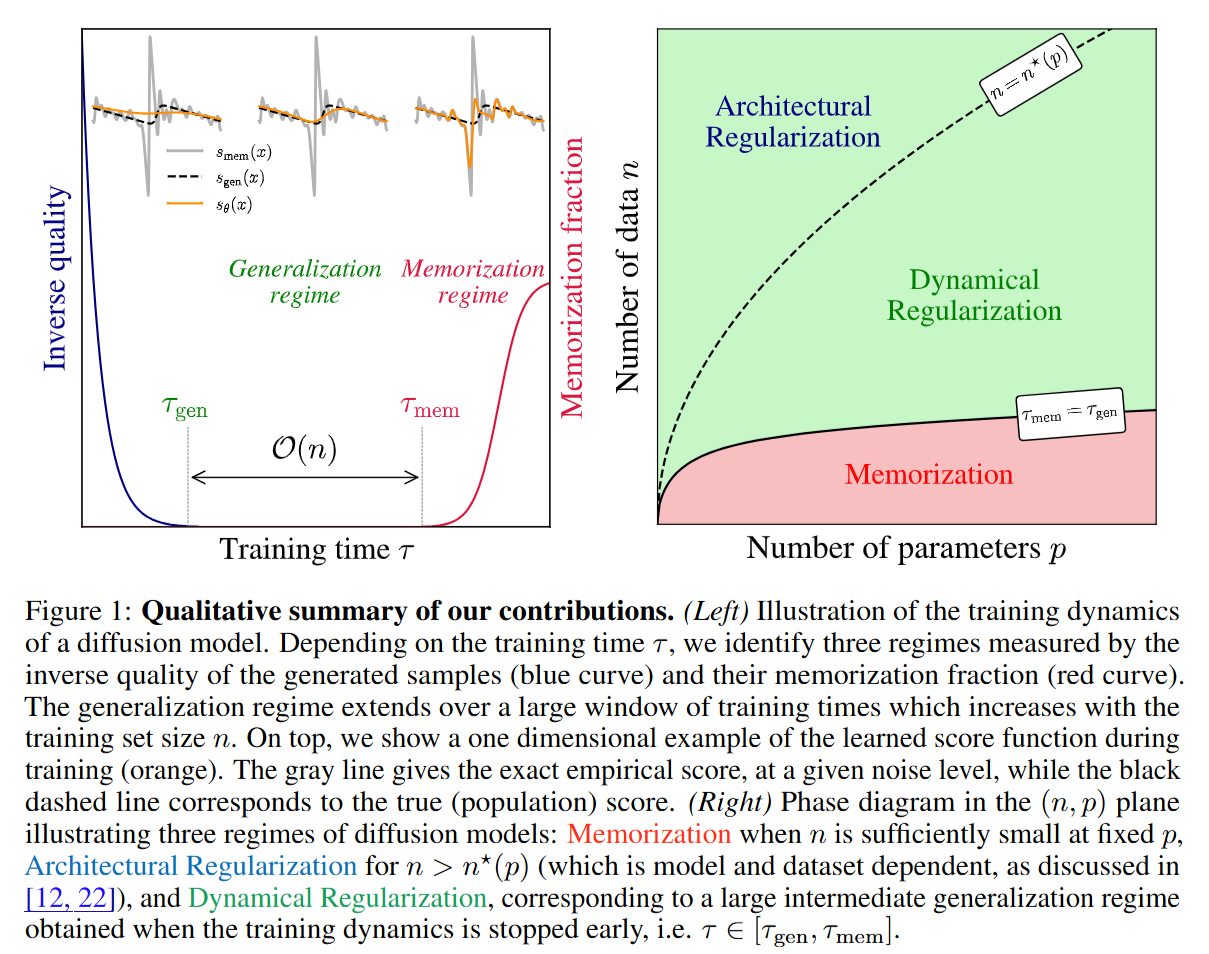

WHAT was done? The authors provide a theoretical and empirical analysis characterizing the training dynamics of score-based diffusion models. Recognizing that models can eventually overfit, they identify two distinct timescales: τgen, when the model learns to generate valid samples, and τmem, when it begins to memorize specific training instances. This work was awarded a Best Paper Award at NeurIPS 2025.

WHY it matters? This work resolves the paradox of why overparameterized diffusion models generalize despite having the capacity to perfectly memorize training data. By proving that τmem scales linearly with the dataset size n while τgen remains constant, the paper establishes that “early stopping” is not just a heuristic, but a structural necessity driven by Implicit Dynamical Regularization. This explains why larger datasets widen the safety window for training, allowing massive models to generalize robustly.

Details

The Empirical Score Paradox

The central tension in training deep generative models lies in the objective function itself. In the context of Denoising Diffusion Probabilistic Models (DDPMs), the network is trained to approximate the score function ∇xlogpt(x). Theoretically, if a model has sufficient capacity and is trained to convergence on a finite dataset of n samples, the optimal solution for the empirical loss is a score field that forces the reverse process to collapse onto the specific training examples—pure memorization. This represents the global minimum of the training objective. Yet, in practice, models like Stable Diffusion generate novel imagery. Previous hypotheses suggested this was due to architectural regularization (e.g., convolution biases) or insufficient capacity. Bonnaire et al. propose a different resolution: the model is saved by the dynamics of Gradient Descent. The system learns the smooth population geometry long before it has time to resolve the sharp, overfitting minima associated with individual data points.

First Principles: The Random Features Proxy

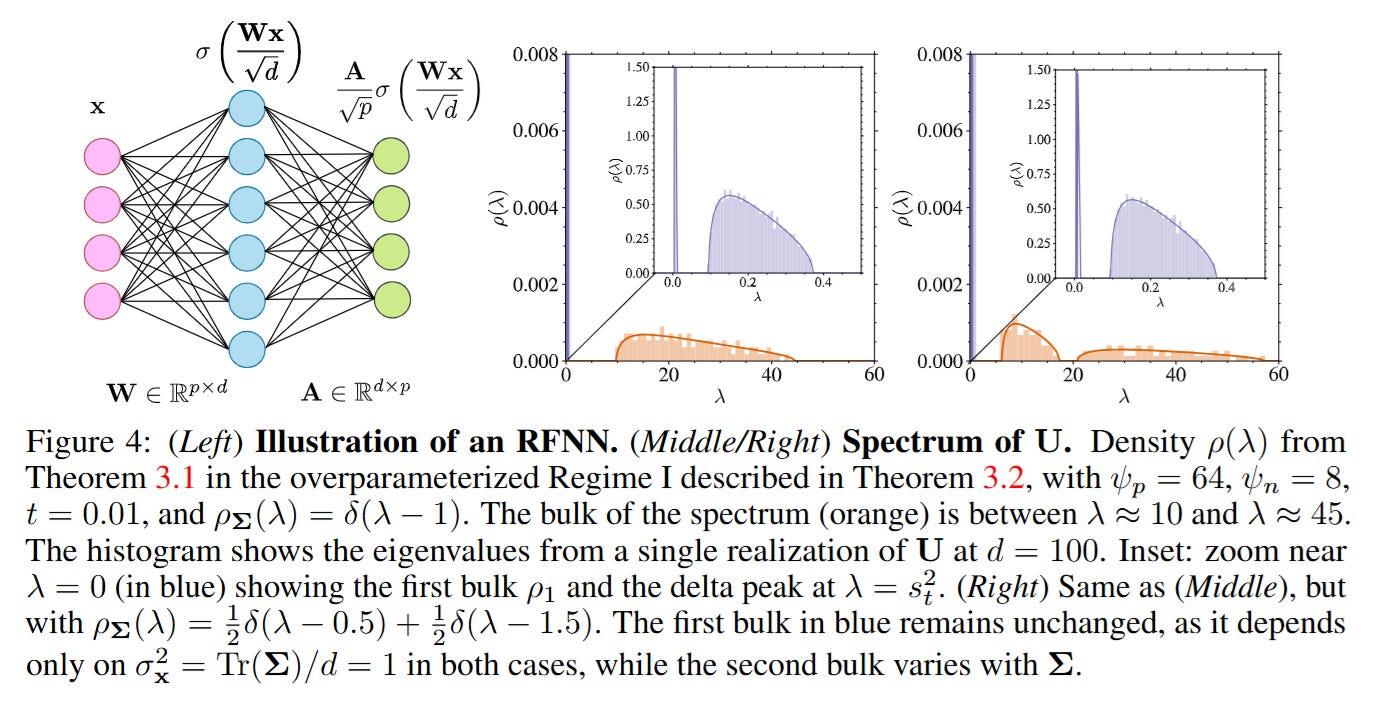

To rigorously analyze these dynamics, the authors abstract the complex U-Net architecture into a high-dimensional Random Features Neural Network (RFNN). In this setting, the score function sA(x) is parameterized by a learnable weight matrix A acting on fixed nonlinear features. Specifically, for input data x∈Rd, the score is modeled as sA(x) = A/sqrt(p) σ(Wx/sqrt(d)), where W is a fixed random matrix and p represents the number of parameters.

The analytical power of this setup comes from the tractability of the training dynamics. The evolution of the weights A under gradient flow is governed by the eigenvalues of the feature correlation matrix U. This allows the authors to leverage Random Matrix Theory to decompose the training process into spectral components. The core mathematical insight is that the loss landscape possesses a “stiff” direction corresponding to the population distribution (large eigenvalues, learned quickly) and “soft” directions corresponding to the finite-sample noise (small eigenvalues, learned slowly).

The Two-Clock Mechanism

The paper validates this spectral theory by tracing the evolution of a specific input through the training lifecycle, using both synthetic data and a U-Net trained on CelebA. The process reveals two distinct phases, visualized clearly in Figure 1.

Initially, the training loss decreases rapidly. During this phase, up to time τgen, the model learns the “bulk” of the spectral distribution. If we sample from the model at this stage, we receive high-quality, diverse images that respect the general manifold of faces but do not replicate specific training examples.

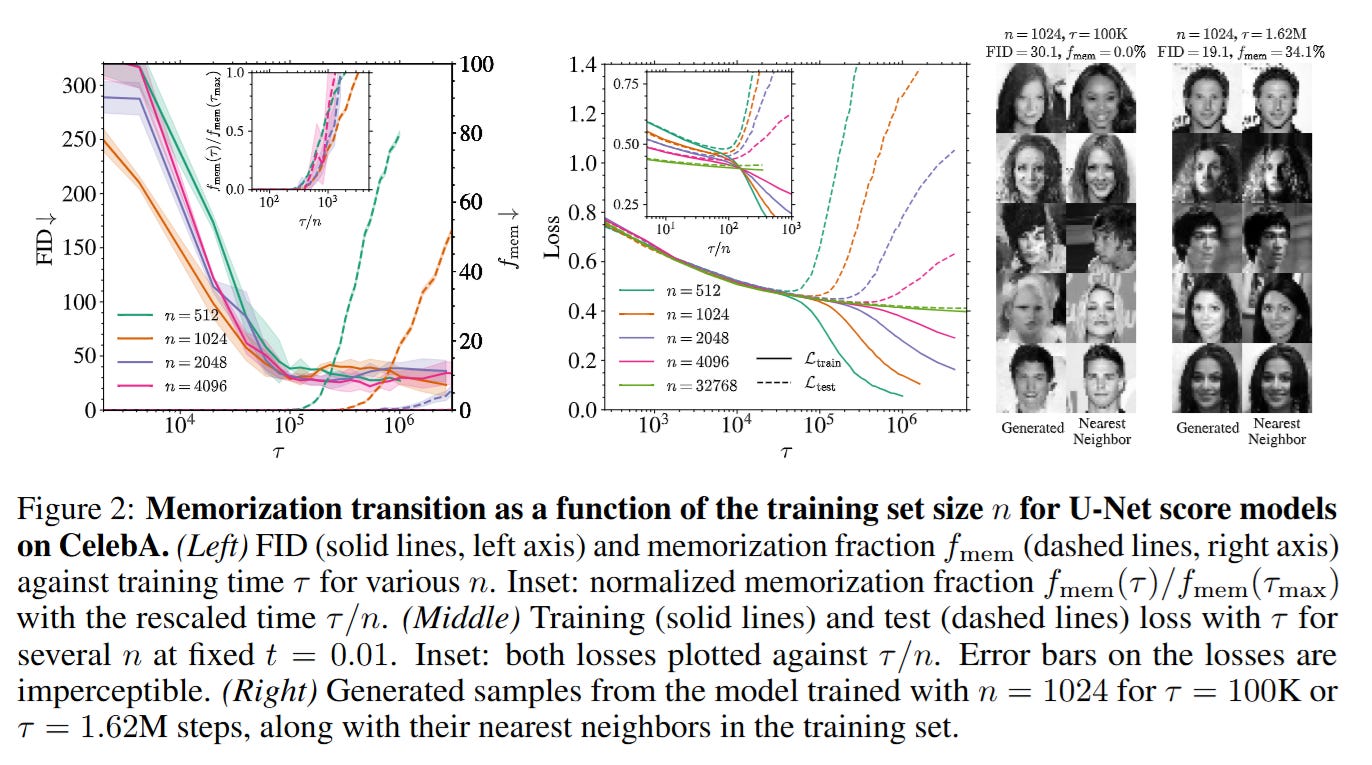

As training continues beyond τgen, the loss curve flattens into a plateau. This is the “Generalization Window.” However, if optimization is allowed to run indefinitely, the system eventually engages with the tail end of the spectrum. At the timescale τmem, the model begins to resolve the high-frequency components of the empirical score—effectively the “spikes” around the n training points. As shown in Figure 2, the Fréchet Inception Distance (FID) stabilizes early, but the memorization fraction fmem stays near zero until τmem is reached, after which it shoots up.

The crucial discovery is the scaling law: τmem∝n. For a fixed model capacity, doubling the dataset size effectively doubles the time before memorization sets in, widening the safety window for training.

Analytical Validation in the High-Dimensional Limit

The authors substantiate the empirical scaling laws with a formal derivation in the asymptotic limit where d,p,n→∞. They utilize the Sokhotski–Plemelj inversion formula to recover the eigenvalue density ρ(λ) of the correlation matrix U. The theoretical analysis in Figure 4 confirms that the spectrum is split into two disjoint supports in the overparameterized regime (p≫n). The first support (bulk) is associated with the population covariance and dictates τgen. The second support is associated with the finite sampling noise.

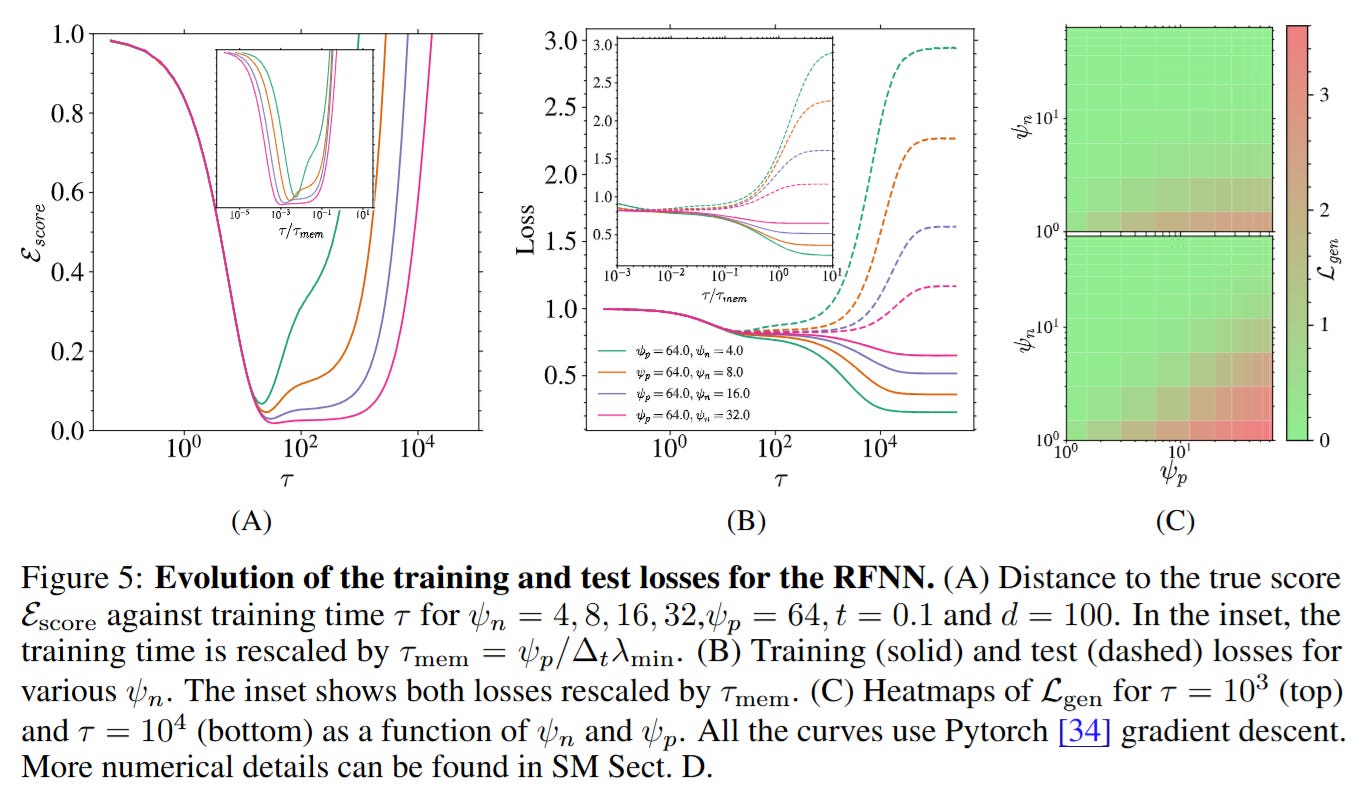

The update rule for the weights in this regime follows a gradient flow A˙(τ)=−d2∇ALtrain. By projecting this dynamics onto the eigenvectors of U, the authors prove that the convergence time for the memorization components is inversely proportional to the smallest eigenvalues in the bulk, leading to the derived scaling τmem≈ψn/Δt, where ψn=n/d. This provides a closed-form justification for why larger datasets push the memorization horizon to infinity.

Analysis: The Stability of Early Stopping

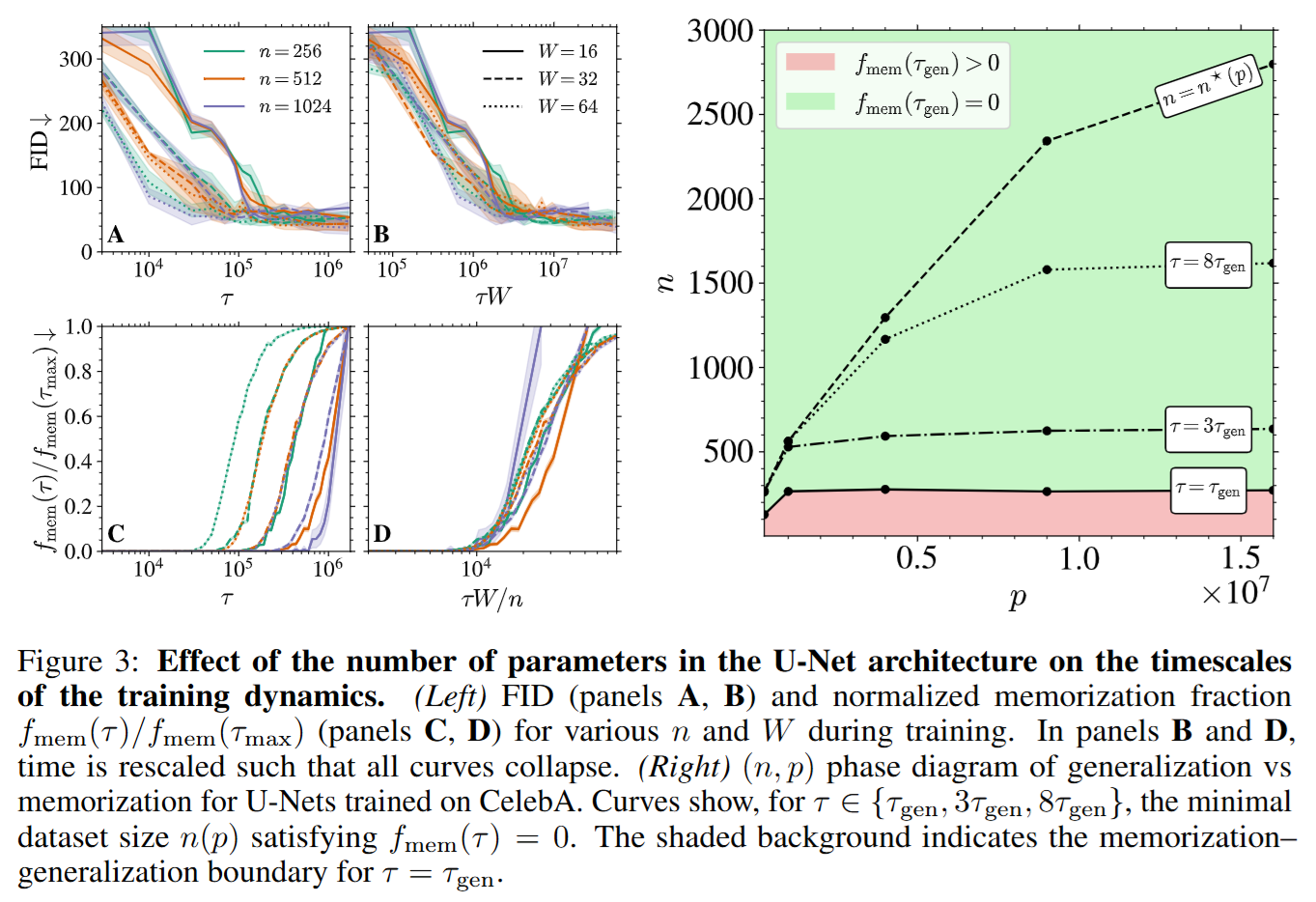

The practical implication of this “Implicit Dynamical Regularization” is that early stopping is not merely a heuristic to prevent rising test error, but a structural necessity for score-based generative modeling. In (Figure 3), the authors map the phase diagram of generalization versus memorization in the (n,p) plane.

They identify a boundary n∗(p) below which the model has enough capacity to memorize. However, because of the time-lag τmem−τgen, there exists a vast operational region where n<n∗ (the model could memorize) but t<τmem (the model hasn’t yet memorized). This explains the success of massive models trained on massive datasets: the time required to overfit the dataset grows so large that it effectively exceeds the compute budget used in practice.

Limitations

While the RFNN analysis provides a rigorous foundation, it simplifies the feature learning capabilities of deep CNNs or Transformers, assuming fixed features in the first layer. The authors acknowledge that while they tested this on U-Nets with SGD, modern implementations often use Adam, which might accelerate the traversal of the eigenvalue spectrum, potentially shrinking the gap between τgen and τmem.

Furthermore, the analysis is primarily conducted on unconditional generation; the dynamics of conditional guidance (e.g., text-to-image) could introduce new spectral properties not captured here.

Impact & Conclusion

Bonnaire et al. provide a compelling, mechanically transparent explanation for the generalization capabilities of diffusion models. By shifting the focus from architectural constraints to training dynamics, they highlight that “time” is a regularizer as potent as weight decay or dropout. For researchers at the frontier of training large-scale generative models, this reinforces the strategy of scaling dataset size n not just for diversity, but to actively delay the onset of memorization, ensuring that the model spends its computational budget learning the manifold rather than the samples.