Reasoning Models Generate Societies of Thought

Authors: Junsol Kim, Shiyang Lai, Nino Scherrer, Blaise Agüera y Arcas and James Evans

Paper: https://arxiv.org/abs/2601.10825

TL;DR

WHAT was done? The authors demonstrate that state-of-the-art reasoning models (like DeepSeek-R1 and QwQ-32B) do not merely perform extended computation; they implicitly simulate a “society of thought”—a multi-agent dialogue characterized by distinct internal personas, conflict, and reconciliation. Through mechanistic interpretability and reinforcement learning (RL) ablations, the study shows that steering models toward conversational behaviors directly improves reasoning accuracy.

WHY it matters? This reframes the “Chain of Thought” (CoT) paradigm from a linear computational scaling law to a social scaling phenomenon. It suggests that the efficacy of test-time compute is mechanistically driven by the model’s ability to instantiate diverse, adversarial perspectives within its activation space. This opens a new avenue for model alignment where we optimize for internal cognitive diversity rather than just output correctness.

Details

The Monologue Bottleneck

The prevailing assumption in the post-OpenAI o1 era is that reasoning performance scales with test-time computation—simply generating more tokens allows the model to “think” longer. However, raw length correlates imperfectly with correctness. The critical bottleneck is not the duration of the thought process, but its quality and structure. Existing instruction-tuned models (e.g., DeepSeek-V3, Llama-3) often fail on complex tasks because they adopt a monologic approach: they linearly generate a single coherent narrative, rarely challenging their own priors. This paper posits that true reasoning capabilities emerge when the model breaks this monologue, simulating an internal adversarial dialogue that mimics human collective intelligence.

First Principles: The Internalized Assembly

The theoretical substrate here is Minsky’s “Society of Mind” applied to the latent space of Large Language Models (LLMs). The authors propose that what we perceive as “reasoning” is an emergent property of the model simulating interactions between diverse perspectives. In this context, a “perspective” is defined not just as a text string, but as a distinct trajectory in the model’s residual stream that encodes specific personality traits (e.g., high Conscientiousness vs. high Openness) and domain expertise. The atomic unit of reasoning, therefore, is the interaction—specifically the “Conflict of Perspectives”—rather than the individual token prediction. The hypothesis is that Reinforcement Learning (RL) implicitly incentivizes the model to learn these social behaviors because they are the most efficient path to solving complex logical problems.

The Mechanism: From Conflict to Resolution

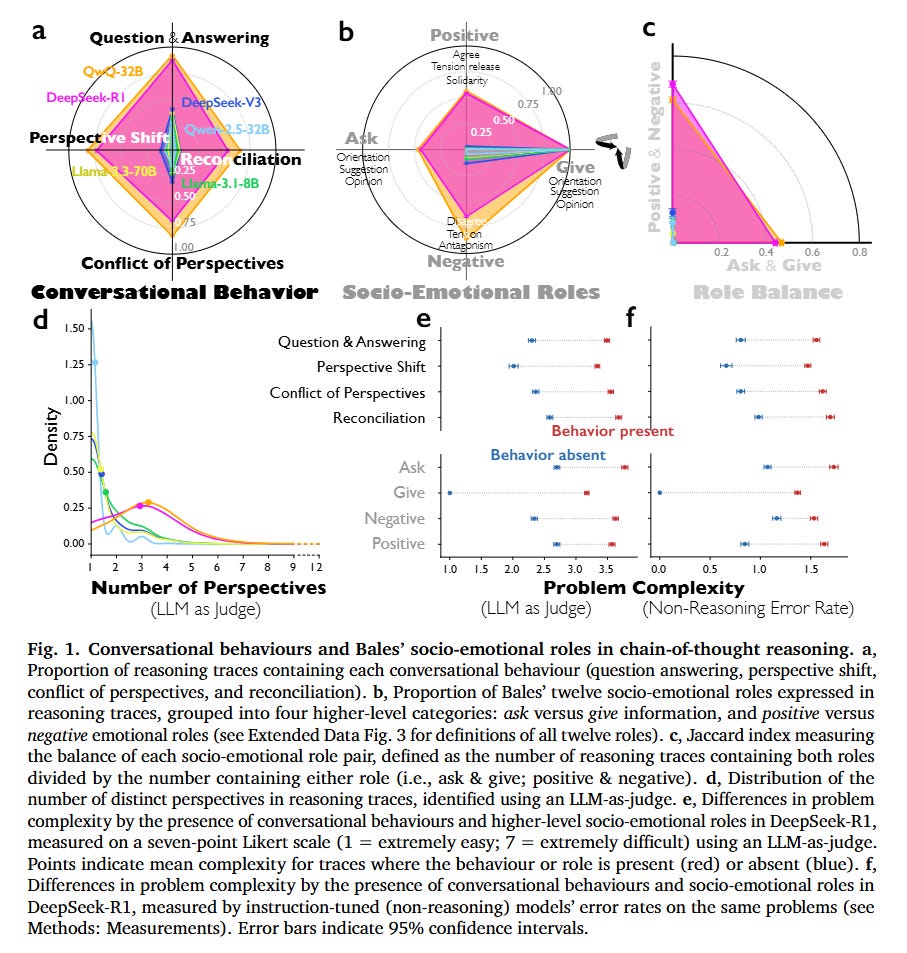

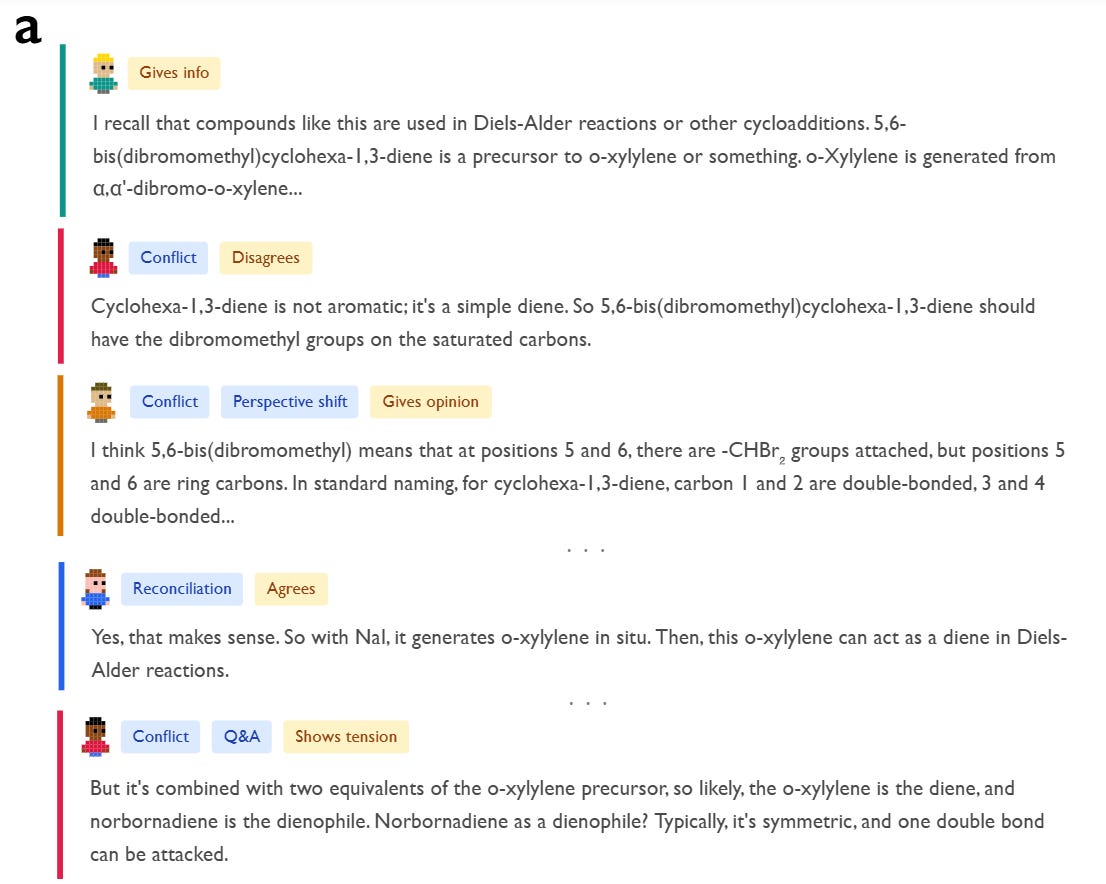

To visualize how this operates, consider the chemistry problem analyzed in the study where the model must identify the product of a multi-step Diels-Alder synthesis. As shown in Figure 1 and the qualitative examples, DeepSeek-R1 does not proceed linearly. Instead, it instantiates distinct personas.

An “Associative Expert” persona proposes a reaction mechanism based on pattern matching. Immediately, a “Critical Verifier” persona—characterized by low Agreeableness and high Neuroticism—interrupts with a “Conflict of Perspectives” behavior, explicitly stating, “Wait, that can’t be right... it’s cyclohexa-1,3-diene, not benzene.”

This internal friction forces a “Perspective Shift,” leading to a new hypothesis. The process concludes with “Reconciliation,” where the conflicting views are integrated into a coherent solution. This contrasts sharply with standard instruction-tuned models, which tend to “hallucinate agreement” with their initial, often incorrect, assumptions. The authors quantify this using an LLM-as-a-judge to tag traces for Bales’ Interaction Process Analysis (IPA) roles, finding that reasoning models exhibit a significantly higher density of reciprocal roles—both “asking” and “giving” orientation—effectively simulating a team meeting within a single forward pass.

Mechanistic Evidence: Steering the “Oh!” Feature

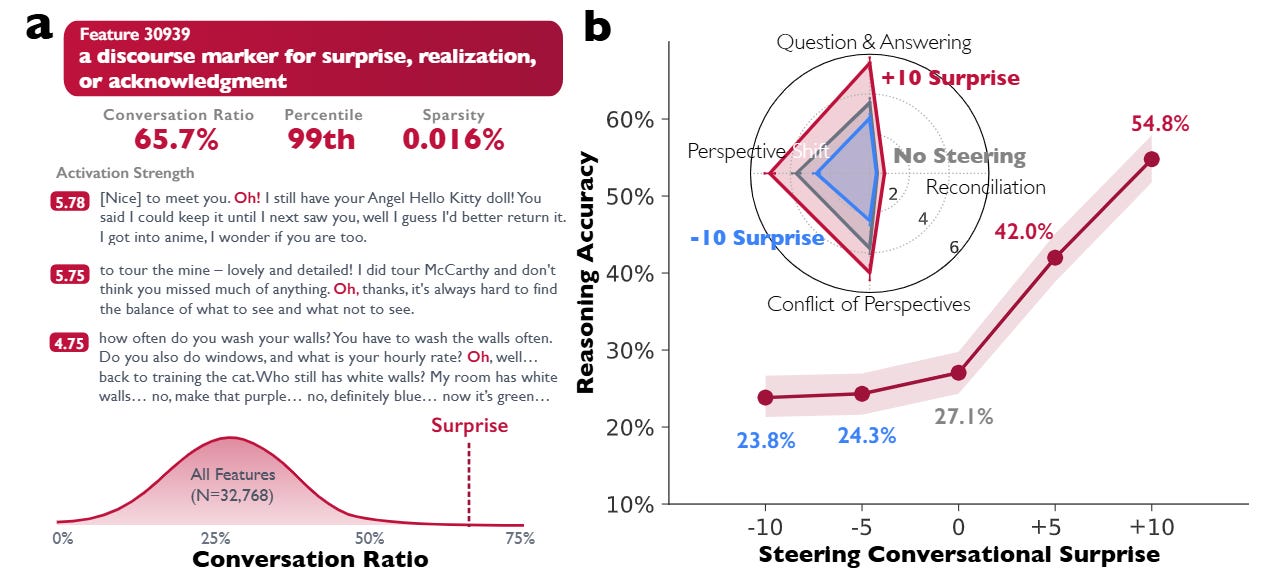

The most compelling evidence comes from the authors’ use of Sparse Autoencoders (SAEs) to inspect the activations of DeepSeek-R1-Llama-8B. They identify a specific feature in the residual stream (Layer 15, Feature 30939) that acts as a discourse marker for surprise, realization, or acknowledgment (often activating on tokens like “Oh!” or “Wait”). This feature has a high “conversation ratio,” appearing primarily in dialogic contexts.

When the authors artificially steer this feature using activation addition—modifying the hidden state ht such that ht′=ht+s⋅d30939 where s is the steering strength—they observe a causal link to performance. As detailed in Figure 2, increasing the steering strength s to +10 on the Countdown arithmetic task nearly doubles the reasoning accuracy from 27.1% to 54.8%. Conversely, negatively steering the feature suppresses conversational behaviors and degrades performance. Structural equation modeling confirms that this improvement is mediated by specific cognitive strategies: the injection of “conversational surprise” triggers downstream behaviors like backtracking and verification, which arguably prevent the model from committing to early errors.

Implementation & RL Dynamics

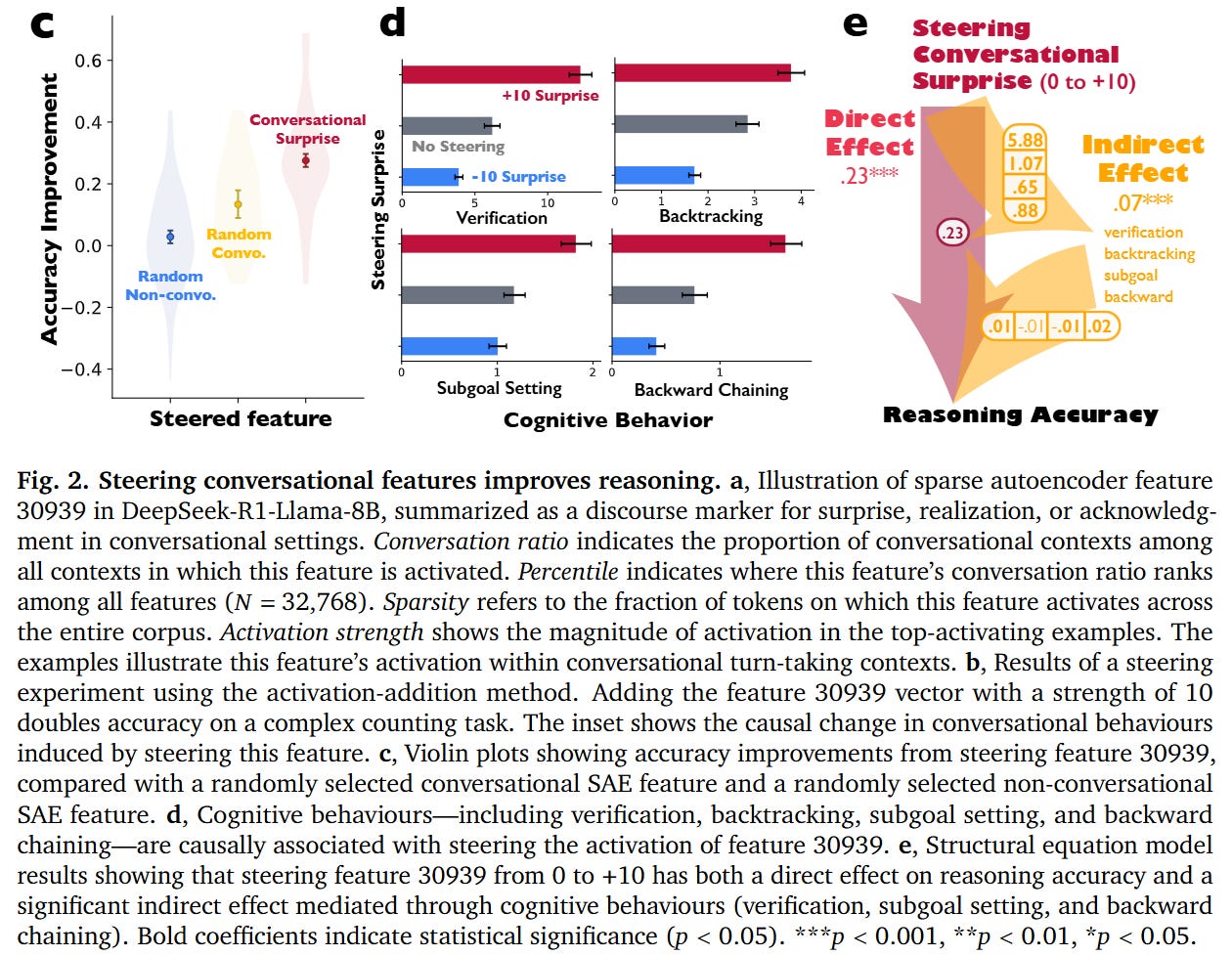

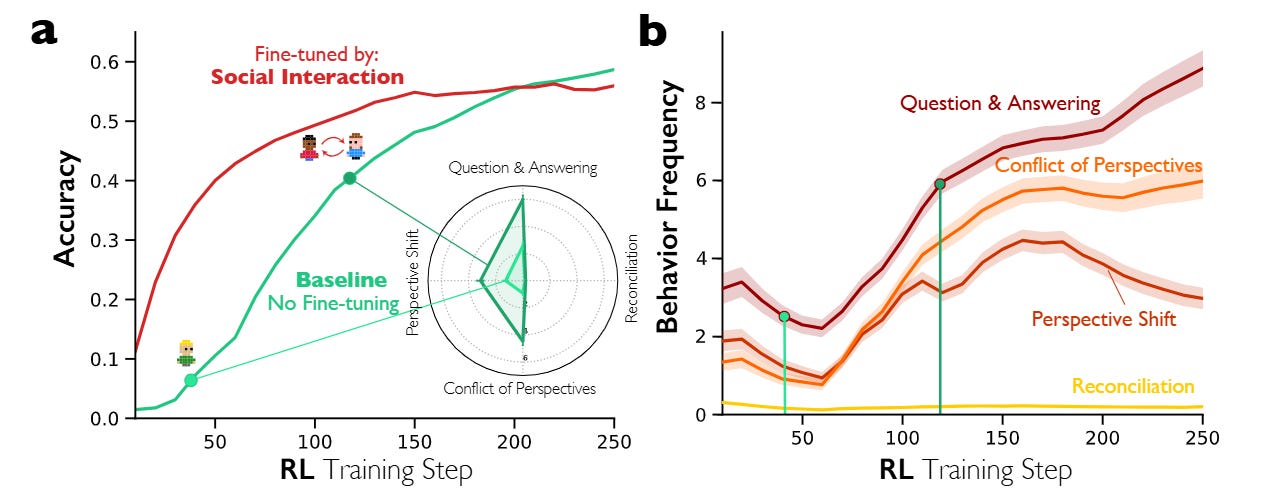

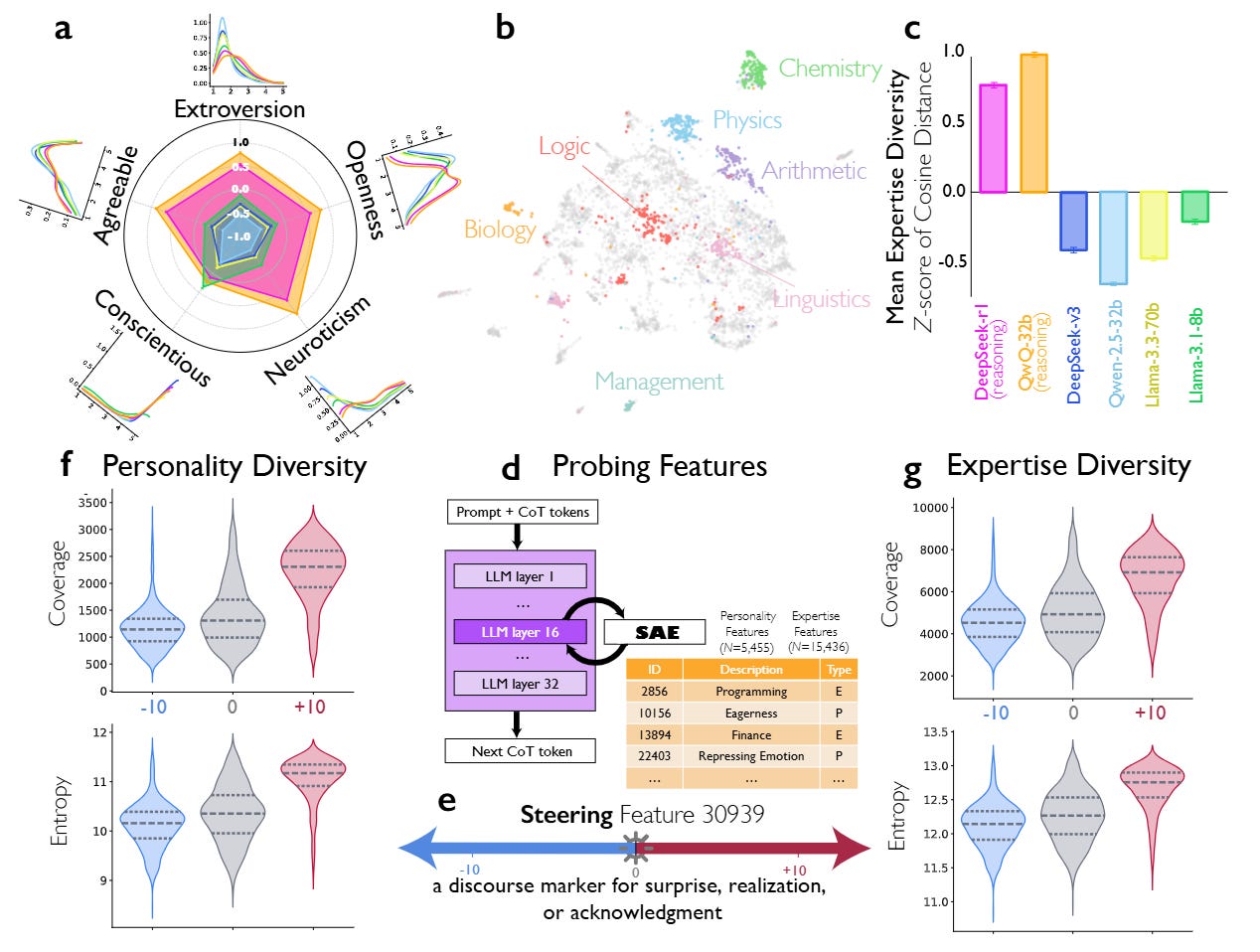

To prove that these behaviors can be induced, the researchers conducted controlled Reinforcement Learning experiments using the Verl framework with Proximal Policy Optimization (PPO). They utilized a reward function balancing accuracy and formatting: R=0.9×Accuracy+0.1×Format. Crucially, they did not explicitly reward conversational tags; they only rewarded the correct answer.

Using Qwen-2.5-3B as a base, they compared a standard baseline against a model “primed” via Supervised Fine-Tuning (SFT) on synthetic multi-agent dialogues. The results in Figure 4 are striking: the conversation-primed models learned significantly faster. By step 40 of RL training, the conversation-primed model reached ~38% accuracy while the monologue-primed model lagged at ~28%. This suggests that “social scaffolding”—explicitly teaching the model to structure thought as a dialogue—provides a superior initialization for the optimization landscape of reasoning tasks. The base model eventually “discovers” these social behaviors on its own, spontaneously increasing the frequency of self-questioning and perspective-shifting as it converges on higher accuracy, validating the hypothesis that sociality is an optimal policy for reasoning.

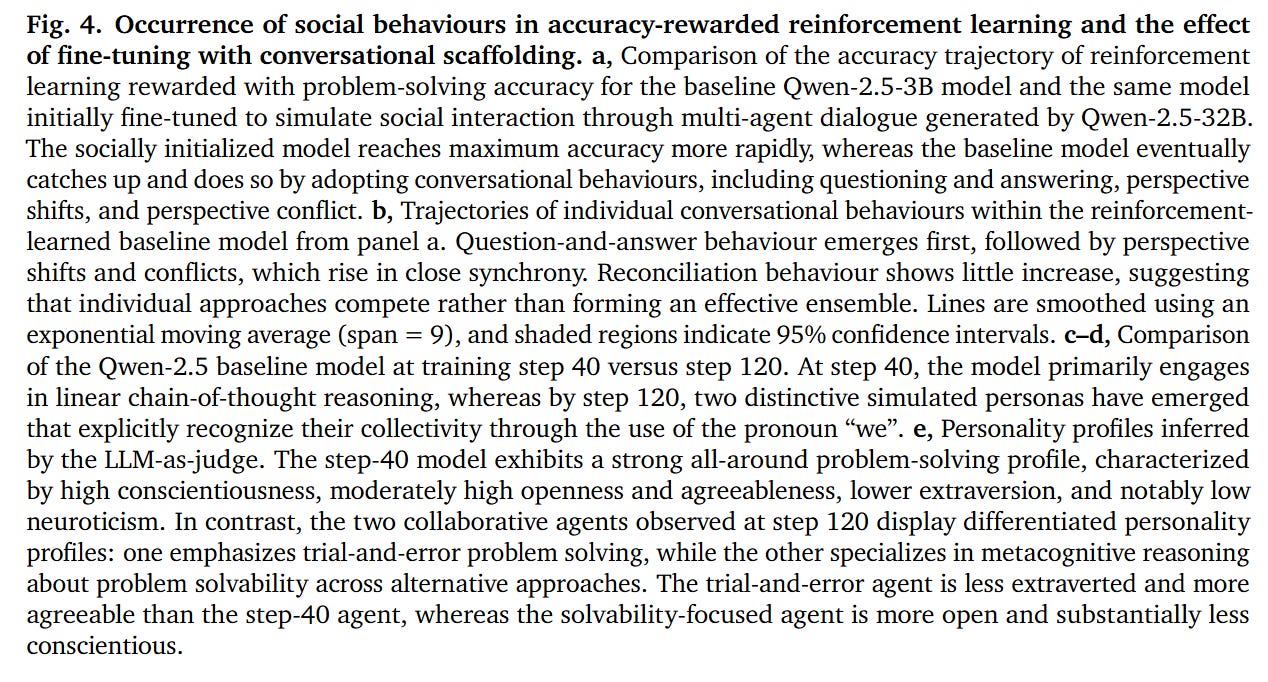

Analysis: Diversity as a Driver

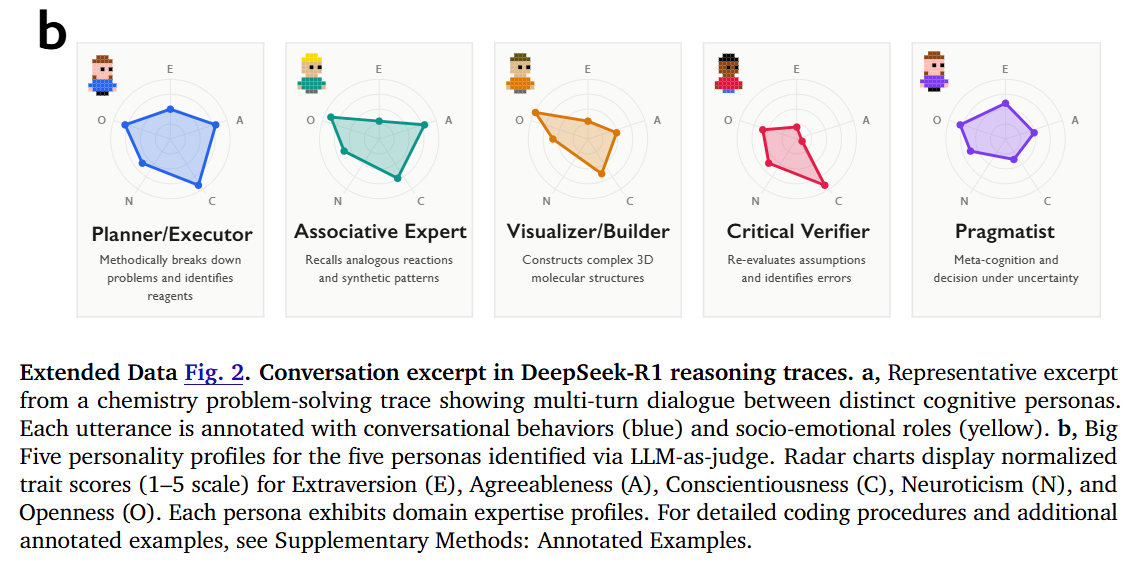

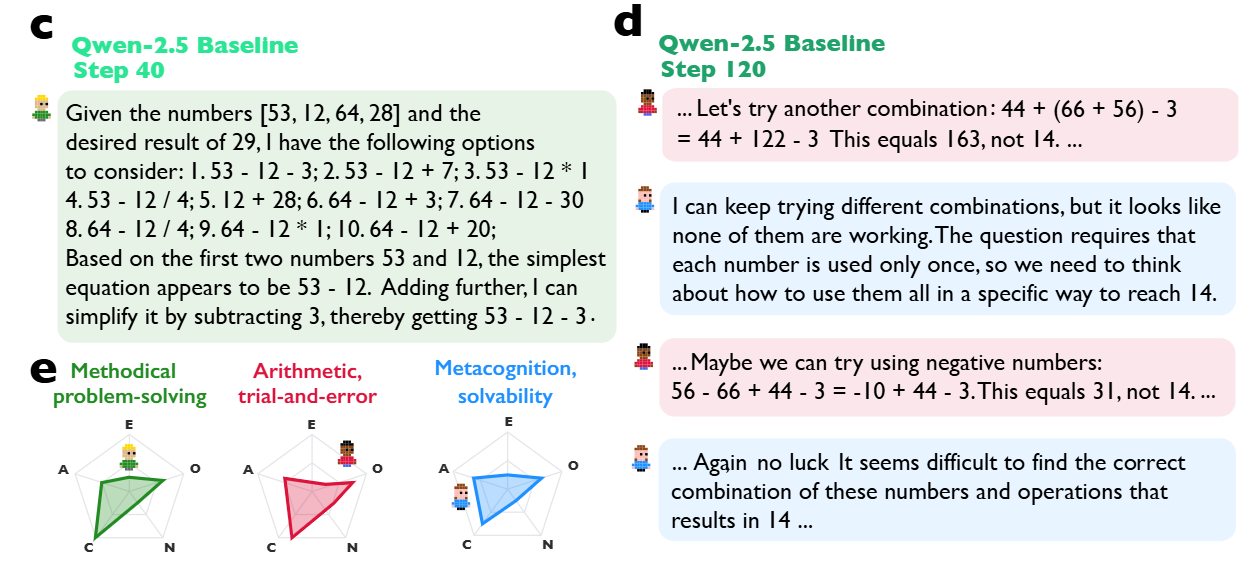

The study delves into the nature of the internal voices using 10-item Big Five Personality measures. Reasoning models like DeepSeek-R1 and QwQ-32B exhibit significantly higher variance in the personality traits of their internal personas compared to non-reasoning baselines. Specifically, they show high diversity in Openness and Neuroticism within a single trace (Figure 3). This mirrors findings in organizational psychology where cognitive diversity in human teams correlates with problem-solving success. The analysis shows that when the model is stuck, it doesn’t just try a new math operation; it spins up a persona with a different “cognitive style” (e.g., a creative ideator vs. a rigid checker) to break the impasse.

Limitations

While the mechanistic evidence is strong, the reliance on LLM-as-a-judge (Gemini-2.5-Pro) to quantify personality traits and conversational moves introduces potential measurement bias, as language models may anthropomorphize text patterns that are merely syntactic. Furthermore, the framing of “society of thought” is inherently metaphorical; while the behaviors mimic social interaction, whether the underlying representational geometry truly maps to distinct agents remains a philosophical interpretation of the statistical reality. Additionally, the RL experiments were conducted on relatively small models (3B parameters) and specific domains (arithmetic, misinformation), leaving open the question of how these dynamics scale to 100B+ parameter training runs where emergent behaviors might differ.

Impact & Conclusion

This paper provides a pivotal mechanistic explanation for why “reasoning” models work. It suggests that the “Chain of Thought” is effective not because it is long, but because it is dialectical. For AI researchers, this implies that future architectures might benefit from explicit multi-agent primitives in the pre-training or fine-tuning data, rather than treating reasoning as a monolithic sequence prediction task. We are likely moving toward “Social Scaling,” where the intelligence of a model is determined by the diversity and effective coordination of the simulated societies it can instantiate during inference.