Teaching Models to Teach Themselves: Reasoning at the Edge of Learnability

Authors: Shobhita Sundaram, John Quan, Ariel Kwiatkowski, Kartik Ahuja, Yann Ollivier, Julia Kempe

Paper: https://arxiv.org/abs/2601.18778

Affiliation: Meta FAIR, MIT, NYU

TL;DR

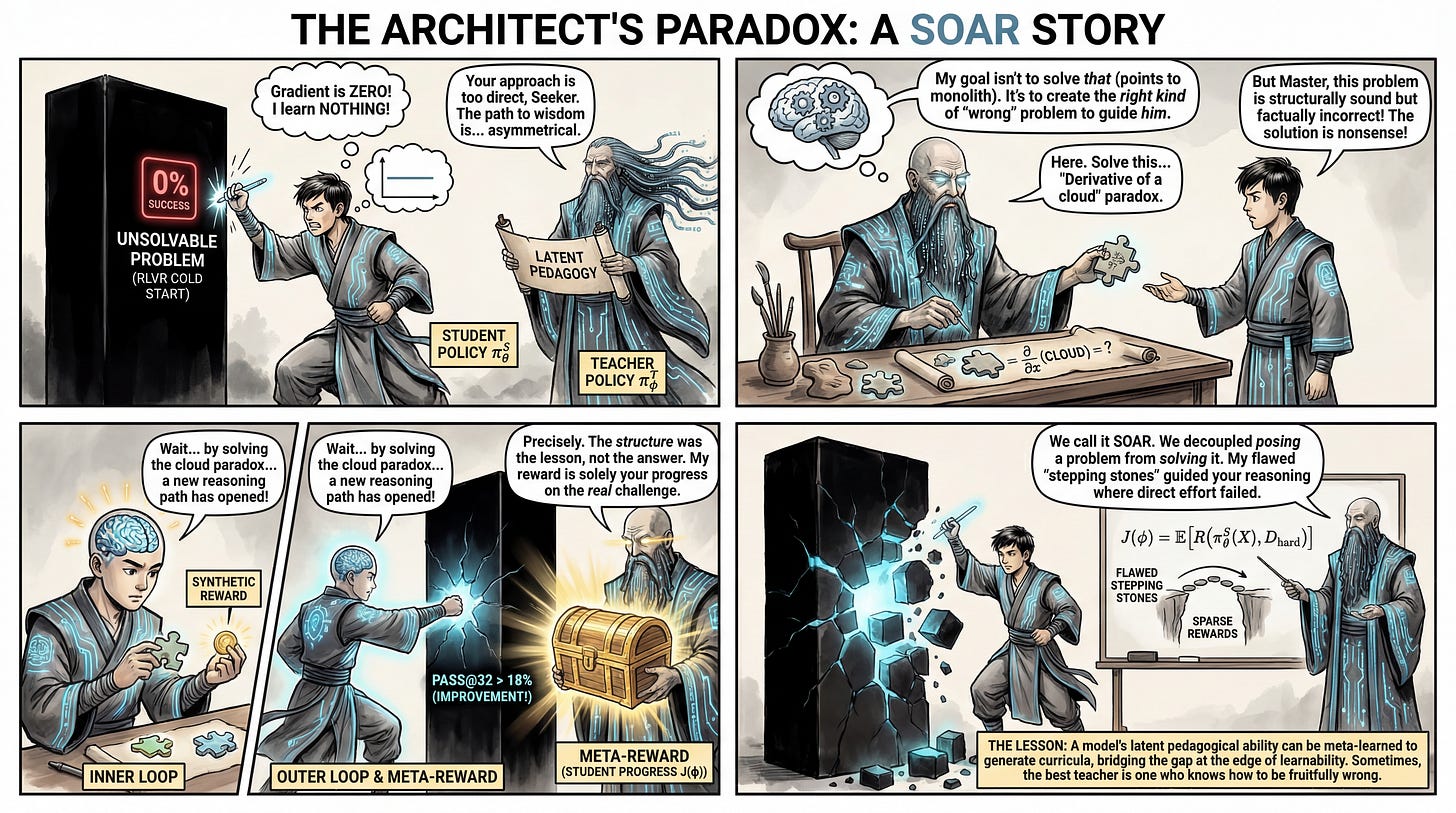

WHAT was done? The authors propose SOAR (Self-Optimization via Asymmetric RL), a bilevel meta-reinforcement learning framework where a “teacher” LLM generates synthetic problems to train a “student” LLM. Unlike standard self-play that optimizes for game outcomes or intrinsic curiosity, the teacher here is explicitly rewarded based on the student’s measured improvement on a set of unsolvable, hard problems.

WHY it matters? This approach effectively solves the “cold start” problem in Reinforcement Learning with Verifiable Rewards (RLVR). When a model cannot solve a single instance of a hard dataset (0% success rate), standard RL fails due to a lack of gradient signal. SOAR demonstrates that models possess a latent “pedagogical” capability—distinct from problem-solving—that can be sharpened via meta-RL to generate useful “stepping stone” curricula, enabling the student to solve problems that were previously out of reach without human-curated data.

Details

The Sparse Reward Barrier in Reasoning

The current paradigm of post-training reasoning models relies heavily on Reinforcement Learning with Verifiable Rewards (RLVR), where models explore reasoning paths and are reinforced by binary success signals (e.g., a correct math answer or passing unit test). However, this paradigm faces a critical bottleneck: the “edge of learnability.” If a problem is too difficult—specifically, if a model yields a 0% success rate across thousands of samples—the reward signal is nonexistent. The gradient is zero, and the model learns nothing.

Previous attempts to bridge this gap have relied on manually curated curricula (easy-to-hard datasets) or intrinsic motivation (rewarding the model for novelty or predicted learning progress). While appealing, intrinsic rewards often lead to instability or “reward hacking,” where the generator produces incoherent or trivial problems that satisfy the proxy objective but fail to transfer to real-world performance. The authors of this paper address this by grounding the curriculum generation process in a concrete, external metric: the student’s actual improvement on a holdout set of “unsolvable” problems.