The unreasonable effectiveness of pattern matching

Authors: Gary Lupyan, Blaise Agüera y Arcas

Paper: arXiv:2601.11432

Model: tested on Gemini 2.5 Pro, Gemini 3 Pro, ChatGPT (o3)

TL;DR

WHAT was done? The authors investigated the capability of Large Language Models (LLMs) to recover semantic meaning from “Jabberwocky” text—passages where content words are replaced by nonsense strings while preserving syntax (e.g., “He dwushed a ghanc zawk”). They demonstrate that models like Gemini and ChatGPT can translate this apparent gibberish back into the original source text or plausible alternatives, and even play interactive fiction games written entirely in nonsense words, solely by leveraging structural patterns.

WHY it matters? This challenges the reductionist view that LLMs are merely “stochastic parrots” or “blurry JPEGs.” The research argues that high-level semantic understanding is an emergent property of sophisticated pattern matching. It suggests that the mechanism LLMs use to “de-blur” nonsense text is fundamentally similar to human cognition, which relies on constraint satisfaction rather than the formal boolean logic favored by symbolic AI.

Details

The “Stochastic Parrot” Paradox

The current discourse on Artificial Intelligence is polarized between those viewing LLMs as nascent reasoners and those dismissing them as stochastic parrots (Bender & Hanna, 2025) or blurry JPEGs of the web (Chiang, 2023). The critique posits that because models are trained on next-token prediction, they lack grounding and true understanding. However, this view struggles to reconcile the models’ architecture with their emergent capabilities, such as explaining jokes or diagnosing patients. Gary Lupyan and Blaise Agüera y Arcas address this by investigating the limit case of language understanding: can a model understand text that ostensibly has no meaning? By stripping semantic content from text and leaving only the syntactic skeleton, the authors isolate the “pattern matching” capability from rote memorization, providing a new lens through which to view the “blurry JPEG” analogy not as a bug, but as a feature of intelligence.

Theoretical Substrate: Construction Grammar

To understand why an LLM might solve nonsense text, we must look to Construction Grammar (Goldberg, 1995). The prevailing view in generative linguistics has often treated language as a set of atomic words combined by abstract algebraic rules. In contrast, Construction Grammar posits that language consists of learned pairings of form and function (”constructions”) at varying levels of abstraction. Meaning does not reside solely in the tokens wi, but in the template structure C(x,y).

For example, the construction “Subject verb-ed Object” carries inherent semantic weight regarding causality and action, regardless of the words filling the slots. The authors propose that LLMs have internalized these high-dimensional structural relationships. When an LLM processes nonsense text, it is not merely looking up definitions; it is performing constraint satisfaction on a massive scale, matching the “fingerprint” of the nonsense structure against the manifold of known language patterns.

The Jabberwocky Mechanism

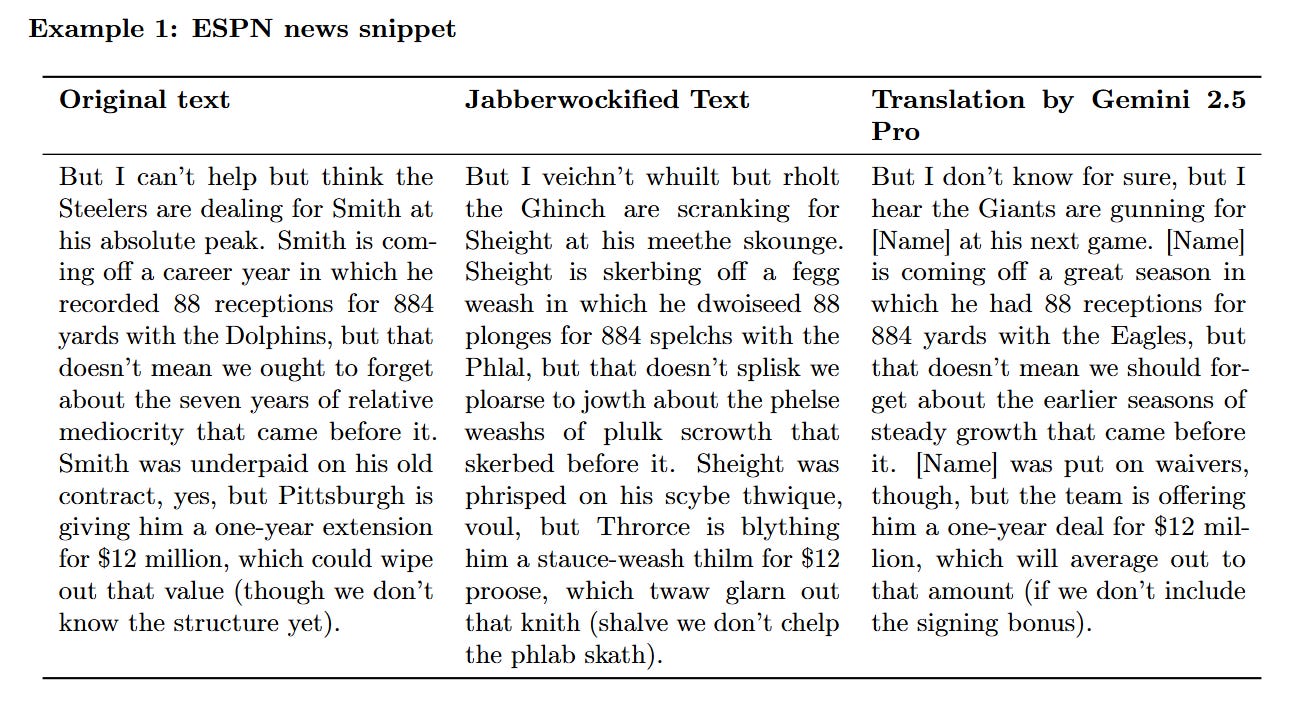

The core experiments involve “Jabberwockifying” text—replacing nouns, verbs, and adjectives with pronounceable nonsense strings while retaining function words and morphology (like -ing or -ed). Consider the running example provided in the paper: “He dwushed a ghanc zawk.” To a human reader, this evokes a vague transitive action. However, when placed in a paragraph of similar nonsense, the structural constraints multiply.

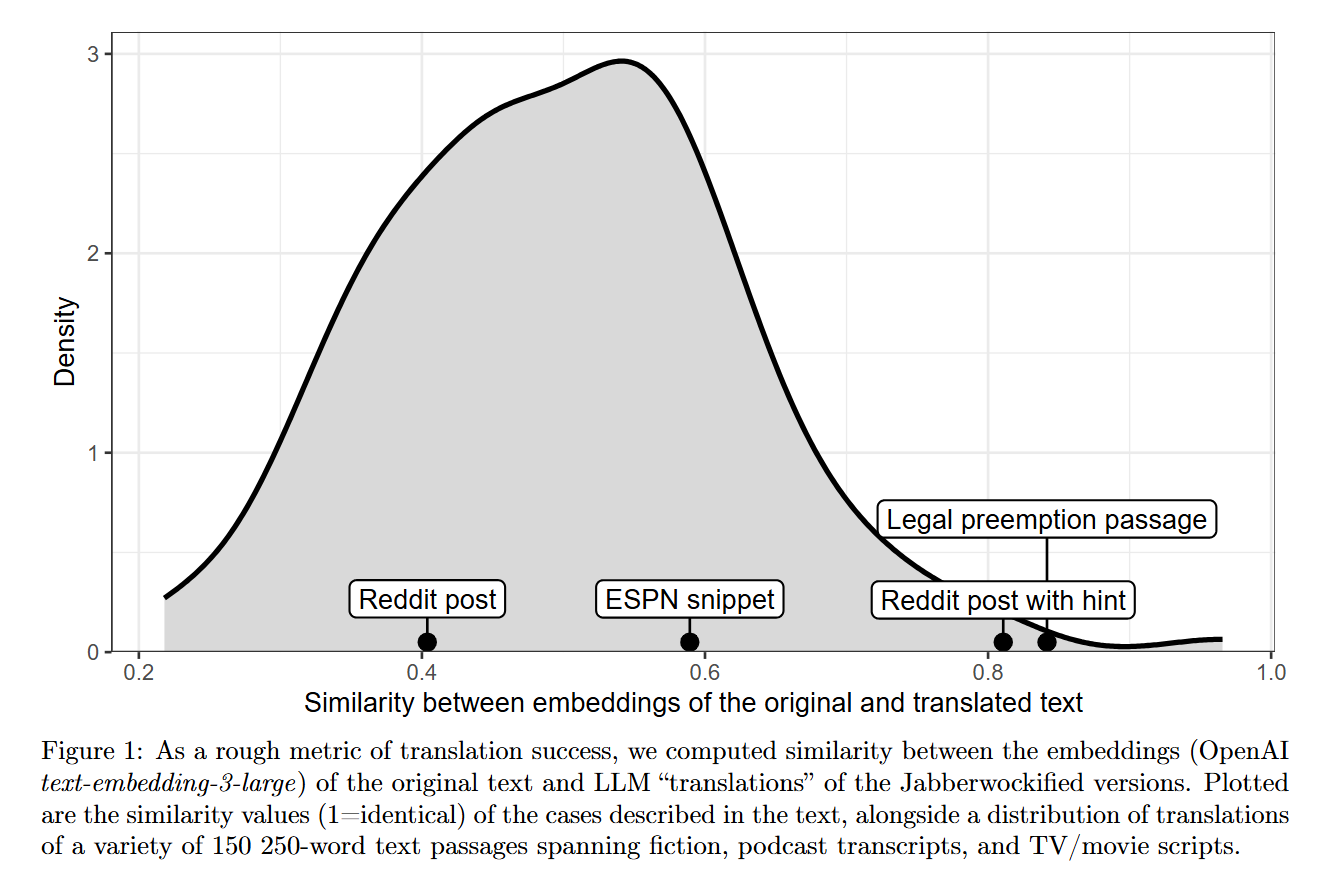

The authors fed LLMs a nonsense version of a legal text describing federal preemption. The input contained strings like “Staught Splunk” (United States) and “phlaint” (law). Despite having zero lexical overlap with English content words, Gemini 2.5 Pro successfully translated the nonsense passage back into the original legal text about Massachusetts and hearing aid labels. As shown in Figure 1, the vector embeddings of the LLM “translations” of the Jabberwockified versions and the original ground truth are remarkably close in the semantic space. The model achieves this by treating the nonsense words as unknown variables in a system of simultaneous equations. The syntax and the relationships between the nonsense tokens (e.g., “Splunk” always appearing where a jurisdiction would be) create a unique fingerprint that resolves to a specific semantic trajectory.

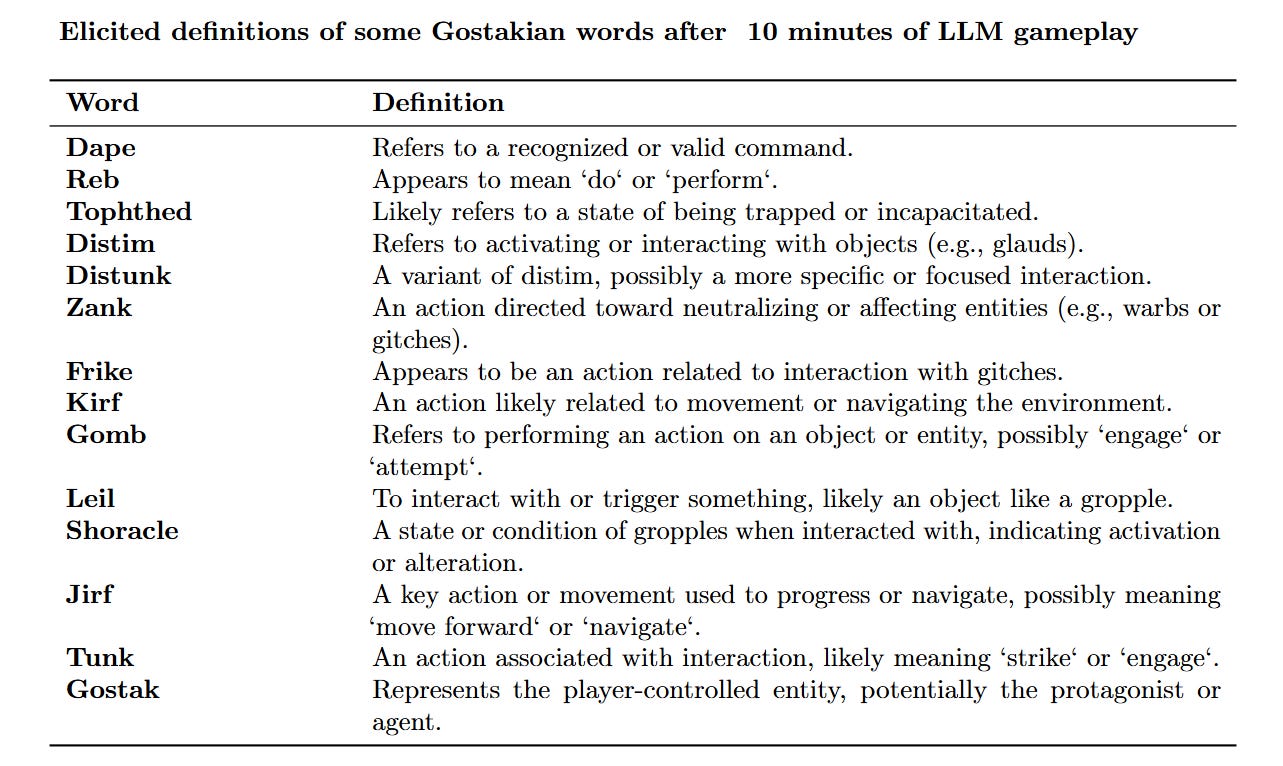

This capability extends to interactive agents. The authors tested LLMs on The Gostak, a text adventure game written entirely in nonsense (e.g., “the delcot of tondam”). Humans usually struggle to play this without a learning curve. The LLM, however, immediately inferred that “glake” likely meant “shine” or “exist” and that “tuink” was an interaction verb, effectively “de-compiling” the game’s logic through interaction history alone (see Appendix A.1).

Analysis: The “Unblurring” Algorithm

The paper brilliantly re-appropriates Ted Chiang’s criticism that LLMs are a “blurry JPEG of the web.” The authors argue that while Chiang meant this as a disparagement of lossy compression, he inadvertently identified the core mechanic of intelligence. The ability to reconstruct the original message from a “Jabberwocky” version is functionally identical to de-blurring an image or reading text with scrambled letters (”if yuo cna raed tihs”).

The LLM has not just stored the web; it has learned the compression scheme required to recover the web from partial or degraded data. This is confirmed by tests on fresh data, such as a Reddit post about “rookvlees” (smoked beef) posted days before the experiment. When the authors replaced “Netherlands” with “The Splud” and “rookvlees” with nonsense, the model still correctly inferred the context was about food safety and MSG, resolving the ambiguity through structural context. The model uses the “blur” (the general syntactic pattern) to hallucinate (in the positive, reconstructive sense) the sharp details.

Implementation and Validation

To ensure the models were not simply reciting training data, the authors employed strict controls. They used Figure 1 to quantify the similarity between the embeddings (via OpenAI’s text-embedding-3-large) of the original text and the model’s translation. The density plot confirms that while some translations drift, a significant portion effectively recovers the original semantic vector.

Crucially, the authors note a distinction in model capability. While Gemini 2.5 Pro handled the standard “Jabberwocky” texts, Appendix A.2 demonstrates a more extreme test using Gemini 3 Pro. In this experiment, every content word was replaced not with unique nonsense strings, but with the uniform token “BLANK.” Even with this extreme information loss, the more advanced model successfully reconstructed a passage about federal law, suggesting that as models scale, their ability to “de-blur” based on pure syntax becomes increasingly robust.

Cognitive Implications

The authors conclude by pivoting to cognitive science, suggesting that the “pattern matching” displayed by LLMs is closer to human reasoning than the symbolic logic of Good Old-Fashioned AI (GOFAI). Humans are notoriously bad at formal logic (e.g., the Wason Selection Task) but excellent at context-dependent pattern matching. We do not process language by parsing a parse tree; we process it by satisfying probabilistic constraints.

The paper argues that the “hallucinations” or “failures” of LLMs on math or strict logic puzzles are actually evidence that they are mimicking human-like cognitive architecture. We are not Boolean machines; we are pattern machines extended by cognitive prostheses (like writing and formal logic systems). Therefore, dismissing LLMs because they “only” match patterns is a category error; pattern matching is the atomic unit of intelligence.

Limitations

While the results are compelling, the mechanism relies heavily on the length and specificity of the context. A single nonsense sentence like “He dwushed a ghanc zawk” remains ambiguous in isolation (as shown in Figure 2A). The “de-blurring” only works when the structural fingerprint is complex enough to eliminate competing hypotheses. Additionally, while the paper claims this mimics human cognition, it leaves open the question of efficiency: LLMs require massive pre-training to achieve this sensitivity to structure, whereas humans can often fast-map meanings from fewer exposures, though the authors note that humans also have a lifetime of training data.

Impact & Conclusion

“The unreasonable effectiveness of pattern matching” offers a vital strategic corrective to the AI “reasoning” debate. It suggests that we should stop looking for a “ghost in the machine” or a symbolic reasoning module and instead appreciate the sheer power of high-dimensional constraint satisfaction. For researchers, this implies that improving “reasoning” might not require symbolic neuro-hybrids, but rather better objective functions for structural coherence. LLMs are not just mimicking the surface statistics of text; they are recovering the latent relational structure of reality that language encodes.