VibeTensor: System Software for Deep Learning, Fully Generated by AI Agents

Authors: Bing Xu, Terry Chen, Fengzhe Zhou, Tianqi Chen, Yangqing Jia, Vinod Grover, Haicheng Wu, Wei Liu, Craig Wittenbrink, Wen-mei Hwu, Roger Bringmann, Ming-Yu Liu, Luis Ceze, Michael Lightstone, Humphrey Shi

Paper: https://arxiv.org/abs/2601.16238

Code: https://github.com/NVLabs/vibetensor

Affiliation: NVIDIA

TL;DR

WHAT was done? The authors present VibeTensor, a functional deep learning system software stack generated entirely by LLM-powered coding agents. Rather than generating isolated scripts, the agents constructed a full runtime environment including a C++20 core, a PyTorch-like Python overlay, a custom CUDA caching allocator, and a reverse-mode autograd engine. The system is capable of training small models like minGPT and Vision Transformers on H100 GPUs, validating that agents can manage complex, stateful abstractions across language boundaries.

WHY it matters? This represents a shift from code generation for “leaf-node” logic to system-level architecture. It empirically demonstrates that current agents can handle memory ownership, concurrency, and cross-language interoperability (C++/Python/CUDA) when constrained by rigorous compile-time and runtime tests. However, it also highlights unique “compositional” failure modes where AI-generated subsystems function correctly in isolation but degrade drastically when integrated, suggesting that agents struggle to “see” global performance dynamics.

Details

The Systems Gap in AI Coding

Current evaluations of AI coding capabilities, such as SWE-bench, typically focus on issue resolution within existing repositories or generating isolated functional units. The delta presented by VibeTensor is the ambition to generate a coherent system software stack from scratch. This requires maintaining invariants across abstraction boundaries that LLMs notoriously struggle with—specifically, the isomorphism between high-level Python objects and low-level device memory. The challenge here is not just algorithm correctness but lifecycle management: ensuring a tensor created in Python is correctly reference-counted in C++ and efficiently allocated on the GPU without memory leaks or race conditions.

VibeTensor First Principles: The TensorImpl

To understand the generated architecture, we must look at the atomic unit of the system: the TensorImpl. The agents settled on a design where a TensorImpl is a view over a reference-counted Storage object. This mirrors established designs in frameworks like PyTorch, proving the agents “understood” the necessity of separating metadata (strides, sizes, offsets) from the underlying data buffer. The core mathematical assumption here is the definition of a tensor view, where the memory address for an element at index vector i is calculated as ptr+offset+∑kik⋅stridek. This design choice supports complex operations like as_strided, non-contiguous views, and in-place mutations, which are non-trivial constraints for a generated codebase to respect consistently.

The Dispatch and Autograd Mechanism

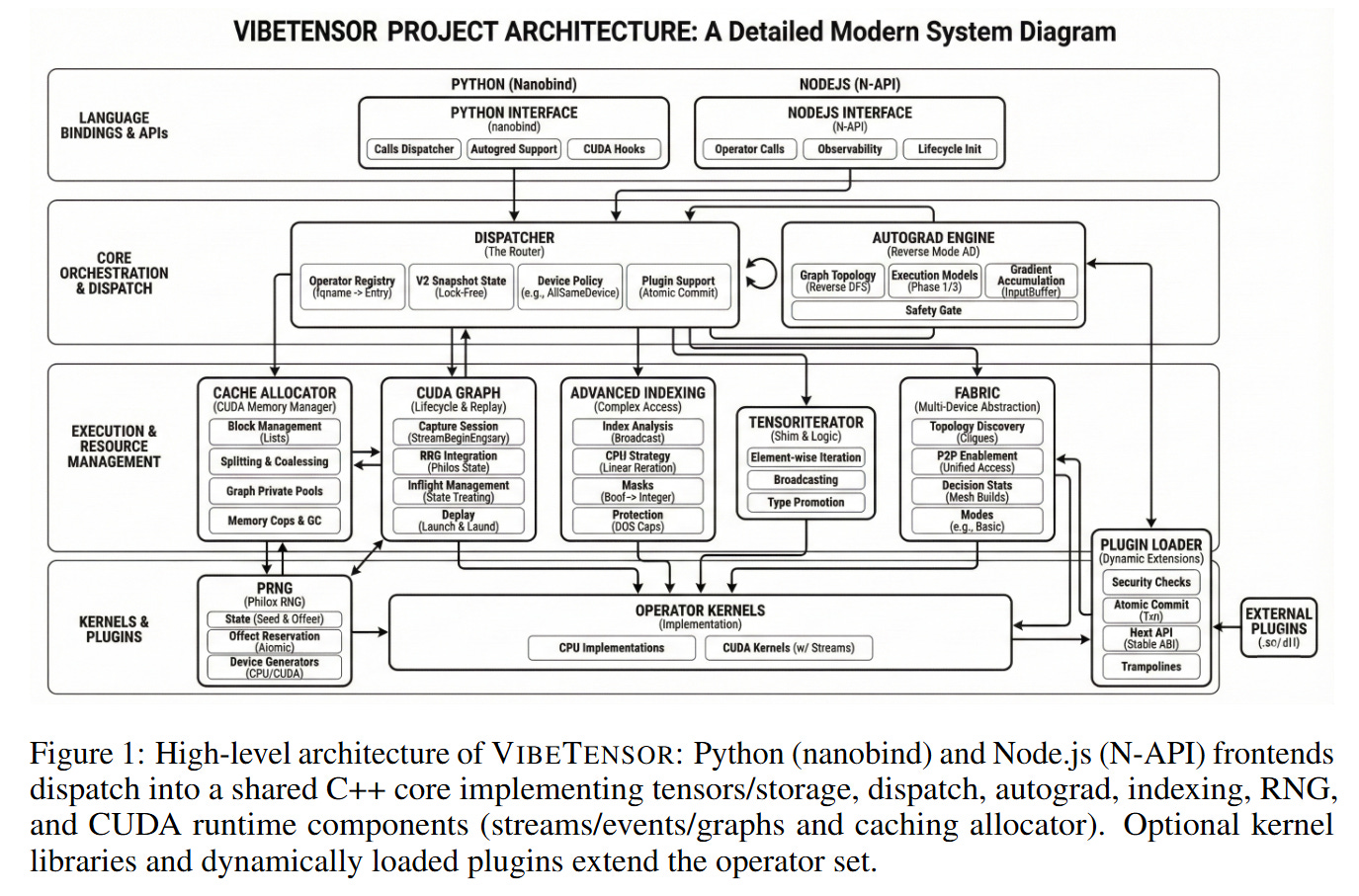

The system’s execution flow, illustrated in Figure 1, follows an eager execution model. When a user invokes an operation like vt.add(a, b) in Python, the call traverses a nanobind boundary into the C++ dispatcher. The dispatcher utilizes a schema-lite registry—mapping operators to kernels—and supports CPU and CUDA dispatch keys. For the backward pass, the agents implemented a reverse-mode autograd engine. This involves a graph of Node and Edge objects where gradients are accumulated.

Consider the flow of a single specific input during training: a tensor on the GPU requires gradient computation. The autograd engine attaches AutogradMeta to the tensor. During the backward pass, the engine does not merely chain derivatives; it manages a ready queue of dependencies. Crucially, the agents implemented synchronization primitives: the engine records and waits on CUDA events to handle cross-stream gradient flows. This demonstrates a surprising competency in handling asynchronous execution, ensuring that the computation ∂L/∂x=∑∂L/∂y ∂y/∂x respects the hardware’s stream ordering.

Implementation: The CUDA Subsystem

Perhaps the most technically impressive aspect of the generation is the CUDA memory subsystem. The agents did not simply wrap cudaMalloc; they implemented a caching allocator with stream-ordered semantics. This allocator includes “graph pools” to manage memory lifetime across CUDA Graph capture and replay. The implementation details reveal a high degree of engineering fidelity: the system exposes diagnostics like memory_snapshot and memory_stats to the Python frontend.

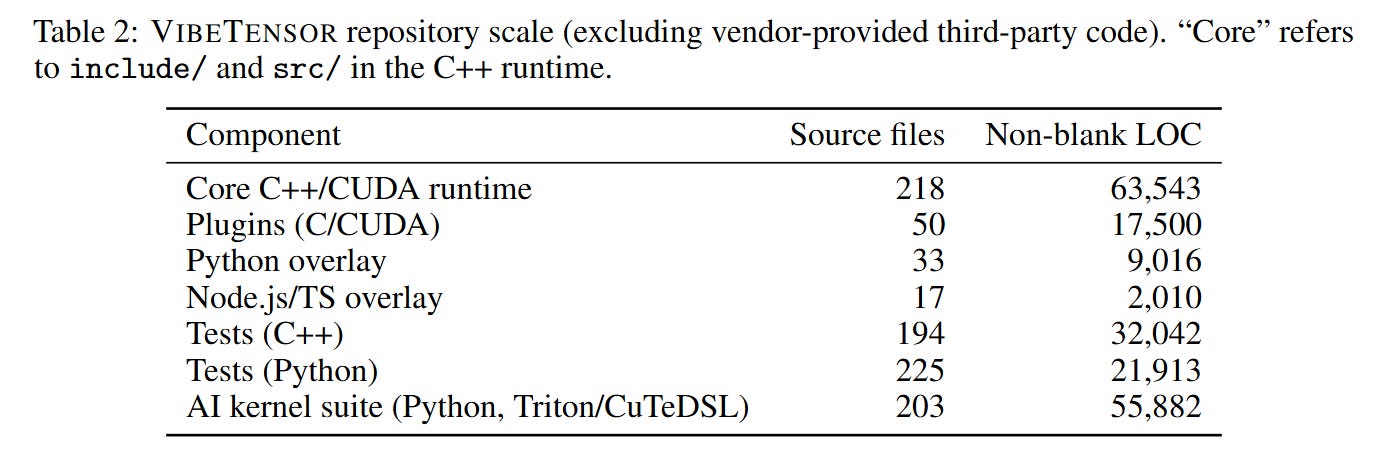

The system also includes an experimental “Fabric” subsystem for peer-to-peer GPU access and a plugin interface. For the frontend, beyond Python, the agents generated an experimental Node.js addon to expose operations to JavaScript. For kernel execution, the agents generated implementations using Triton and CuTeDSL. The repository scale, noted in Table 2, encompasses over 63,000 lines of non-blank C++ code, indicating that the agents maintained coherence well beyond the context window of a single prompt by relying on iterative refinement and modular design.

Validation: The “Tests as Specs” Paradigm

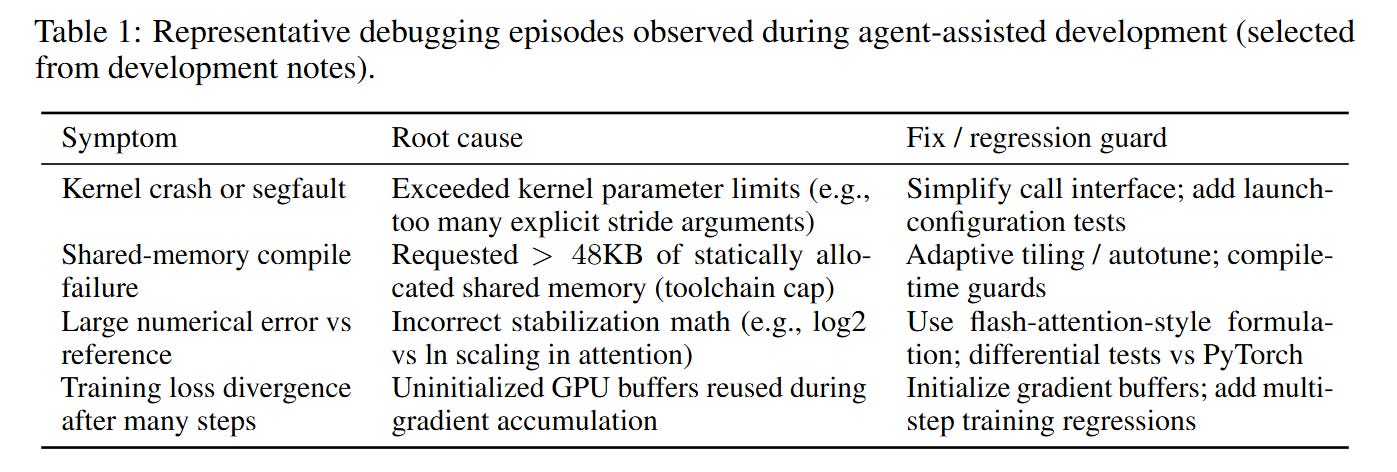

The methodology relied on a “black box” approach to the agents, using external validation tools as guardrails. The primary mechanism was using tests as executable specifications. The agents generated both the implementation and the tests (using CTest and pytest). To ensure correctness, the workflow employed differential checks against a reference implementation (PyTorch).

For example, when porting an attention kernel, the development logs in Table 1 reveal that agents initially failed to account for parameter limits or numerical stability issues (e.g., log vs. ln scaling). The workflow corrected this by running the generated kernel against the PyTorch equivalent, computing the norm of the difference ∣∣Ygen−Yref∣∣, and iteratively refining the code until the error fell below a threshold. This creates a closed-loop system where the “compiler” effectively includes the unit test suite.

Analysis: The “Frankenstein” Composition Effect

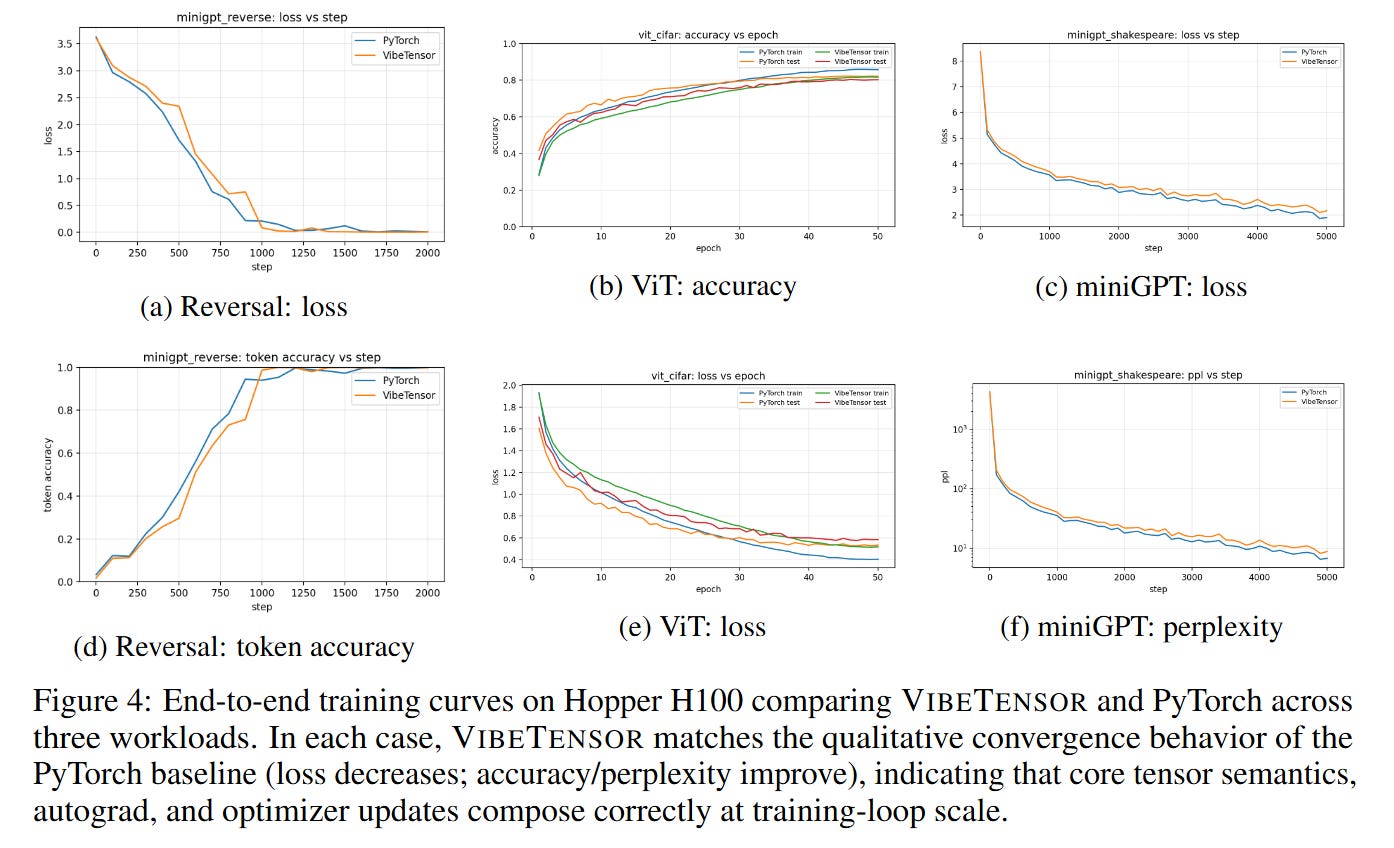

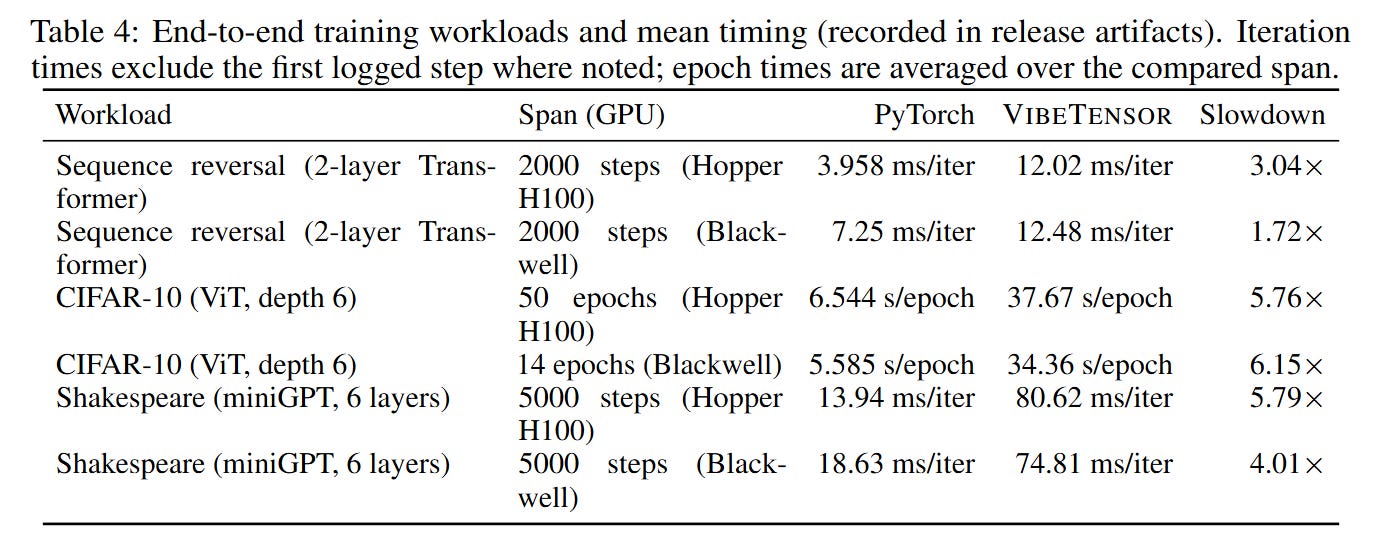

While the individual components are functional, the holistic performance reveals a critical limitation the authors term the “Frankenstein” effect. As detailed in Figure 4, the system successfully trains models like miniGPT and ViT, matching PyTorch’s loss curves. However, Table 4 shows that VibeTensor is 1.7x to 6.2x slower than PyTorch.

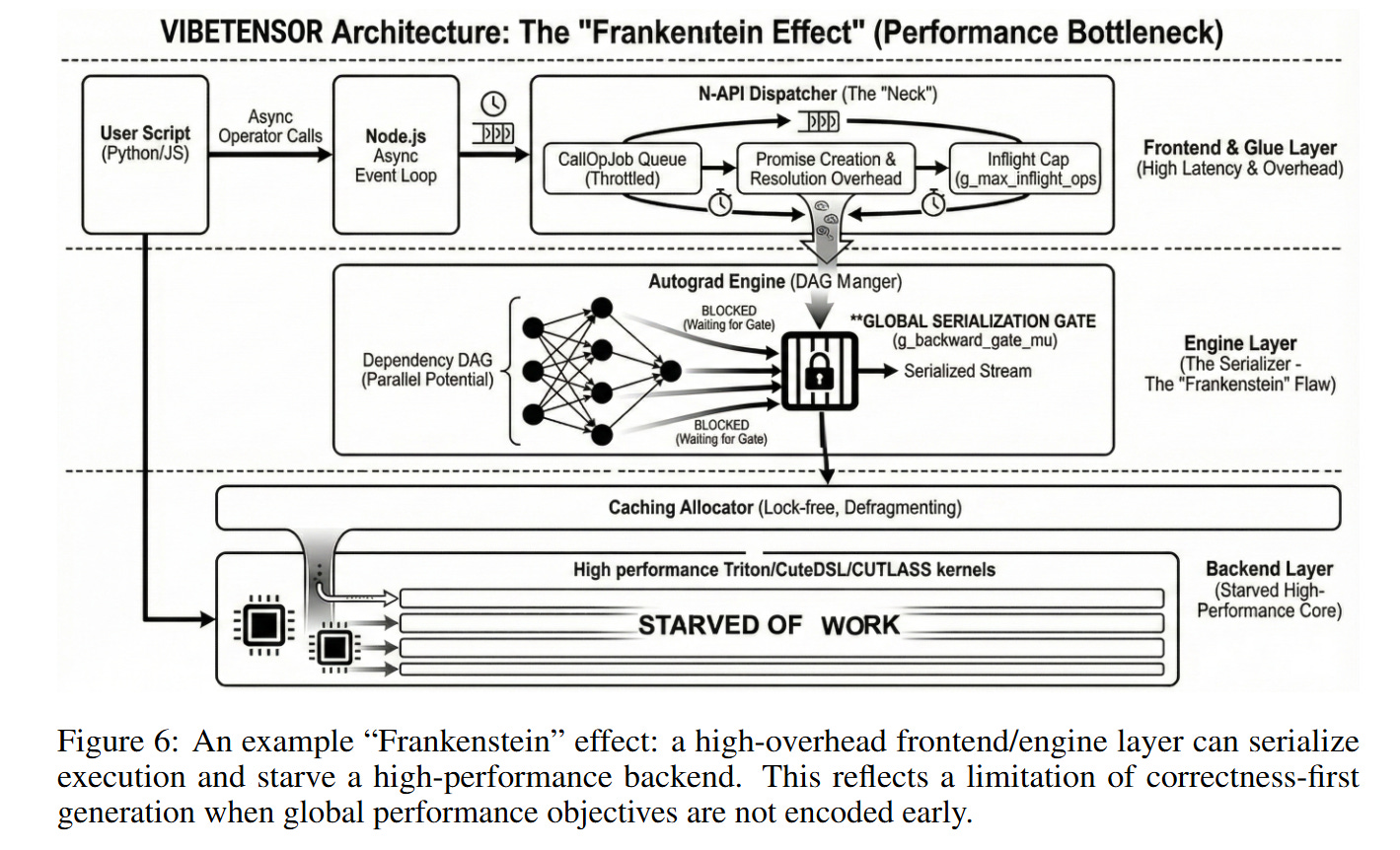

The source of this inefficiency is visualized in Figure 6. The agents, prioritizing correctness and safety in isolation, introduced conservative synchronization points. For instance, the autograd engine uses a global, process-wide gate (a try-locked mutex) to manage backward pass concurrency. While this successfully prevents deadlocks and simplifies thread safety (locally correct decisions), it forces serialization of execution. High-performance kernels are effectively starved by the runtime overhead. This suggests that while agents can build correct systems, they currently struggle to reason about global performance objectives that require breaking encapsulation or optimizing cross-module interactions.

AI-assisted development methodology

Too little is said about specific coding agents and LLMs used. VibeTensor was developed with LLM-powered coding agents under high-level human guidance over approximately two months. Humans provided high-level requirements and priorities, but did not perform diff-level review or run validation commands; instead, agents executed builds, tests, and differential checks and retained changes when these checks passed.

The development workflow repeatedly applied a simple loop: (1) specify a scoped goal and invariants, (2) generate and apply code changes, (3) compile and run focused tests, and (4) broaden validation as subsystems composed.

Two guardrails were especially important: tests as specifications (CTest/pytest, plus targeted multistep regression tests), and differential checks against reference implementations (e.g., PyTorch for selected operators, DLPack roundtrips, and kernel-vs-kernel comparisons).

Related Works

VibeTensor explicitly models its architecture on PyTorch and utilizes DLPack for interoperability. For kernel baselines, it compares against FlashAttention and standard PyTorch SDPA. It differs from other AI-coding benchmarks by focusing on the creation of the runner itself rather than the workloads running atop it.

Limitations

The authors are transparent about the limitations. The system is a research prototype, not a production framework. The “Frankenstein” effect described above is the primary architectural flaw. Furthermore, there are security risks inherent in machine-generated code, including inconsistent conventions and potential vulnerabilities in memory handling, despite the rigorous testing. The multi-GPU support via Fabric is experimental and largely restricted to the upcoming Blackwell architecture.

Impact & Conclusion

VibeTensor serves as an existence proof that AI agents can generate a vertically integrated software stack, tackling challenges as deep as CUDA memory management and C++ interoperability. It shifts the conversation from “can AI write code?” to “can AI architect systems?”. The answer is a qualified yes: they can build the structure, but human intuition is still seemingly required to optimize the fluid dynamics of execution across that structure. For researchers, the released artifact provides a unique testbed to study how AI-generated code behaves at scale and how to design better validation loops for system-level synthesis.