SpikingBrain Technical Report: Spiking Brain-inspired Large Models

Authors: Yuqi Pan, Yupeng Feng, Jinghao Zhuang, Siyu Ding, Zehao Liu, Bohan Sun, Yuhong Chou, Han Xu, Xuerui Qiu, Anlin Deng, Anjie Hu, Peng Zhou, Man Yao, Jibin Wu, Jian Yang, Guoliang Sun, Bo Xu, Guoqi Li

Paper: https://arxiv.org/abs/2509.05276

Code: https://github.com/BICLab/SpikingBrain-7B

TL;DR

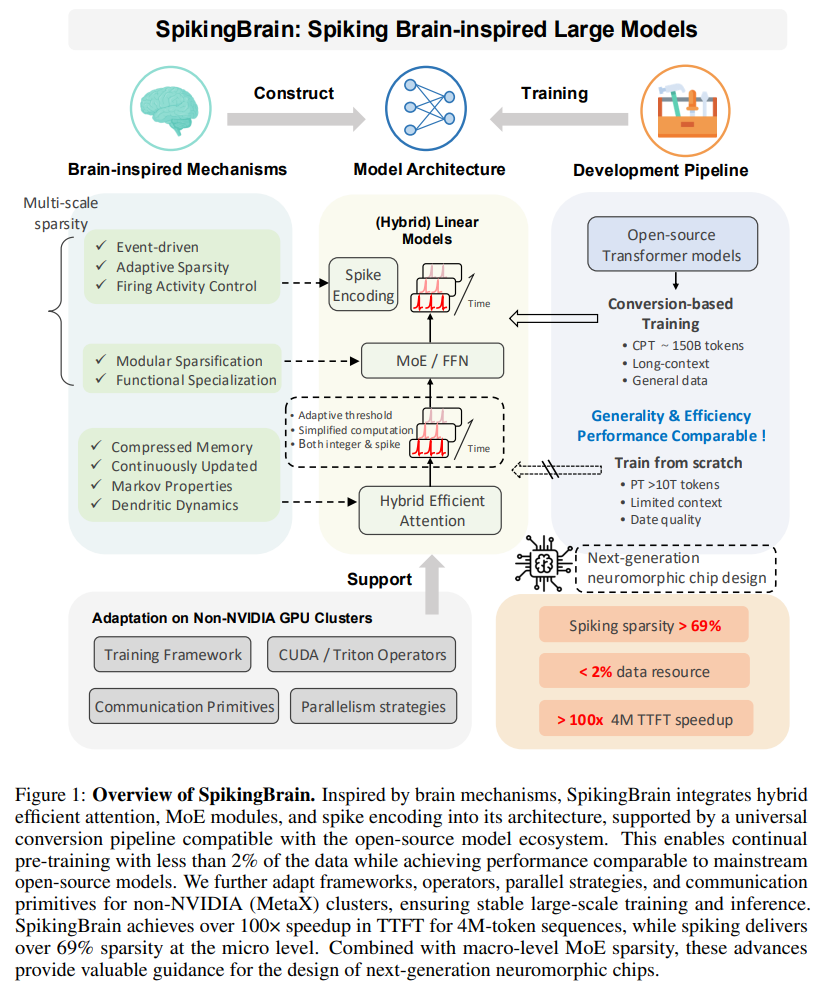

WHAT was done? The paper introduces SpikingBrain, a comprehensive framework for developing efficient, brain-inspired Large Language Models (LLMs). The authors present two models, SpikingBrain-7B (linear) and SpikingBrain-76B (hybrid-linear MoE), which integrate three core innovations: 1) Hybrid Architectures combining linear, sliding-window, and standard attention with adaptive spiking neurons and sparse Mixture-of-Experts (MoE) to achieve near-linear complexity; 2) Efficient Conversion Training, a pipeline that adapts pre-trained Transformers using less than 2% of the typical training data; and 3) Custom System Engineering to enable stable, large-scale training and deployment on a non-NVIDIA (MetaX) GPU cluster. The framework also includes a novel spiking scheme that achieves over 69% activation sparsity for low-power, event-driven inference.

WHY it matters? This work represents a significant step towards sustainable and scalable AI by demonstrating a practical alternative to the resource-intensive paradigm of mainstream Transformers. It proves the feasibility of achieving competitive performance on non-NVIDIA hardware, a vital step in breaking vendor lock-in and fostering a more competitive AI hardware market. The reported >100x inference speedup for 4M-token sequences and substantial energy savings create a viable path for deploying powerful, long-context LLMs on resource-constrained platforms, including edge and mobile devices. By successfully integrating principles from neuroscience into a full-stack hardware and software solution, SpikingBrain provides a compelling blueprint for the next generation of energy-efficient AI and neuromorphic computing.

Details

The dominant narrative in large language models has long been one of brute-force scaling: more parameters, more data, more compute. While this approach has yielded remarkable capabilities, it has also led to significant efficiency bottlenecks, with training costs and inference memory demands that scale poorly with sequence length. A recent technical report introduces SpikingBrain, a compelling framework that challenges this paradigm by drawing inspiration from the most efficient computational device known: the human brain. This work presents not just a novel architecture but a complete, practical pipeline for developing and deploying brain-inspired LLMs on non-NVIDIA hardware, signaling a potential shift from a purely compute-driven to an energy-optimized future for AI.

Methodology: A Three-Pillar Approach to Efficiency

The SpikingBrain framework is built on three interconnected pillars: model architecture, algorithmic optimization, and system engineering. This holistic approach addresses efficiency at every level of the stack (Figure 1).

1. Brain-Inspired Model Architectures

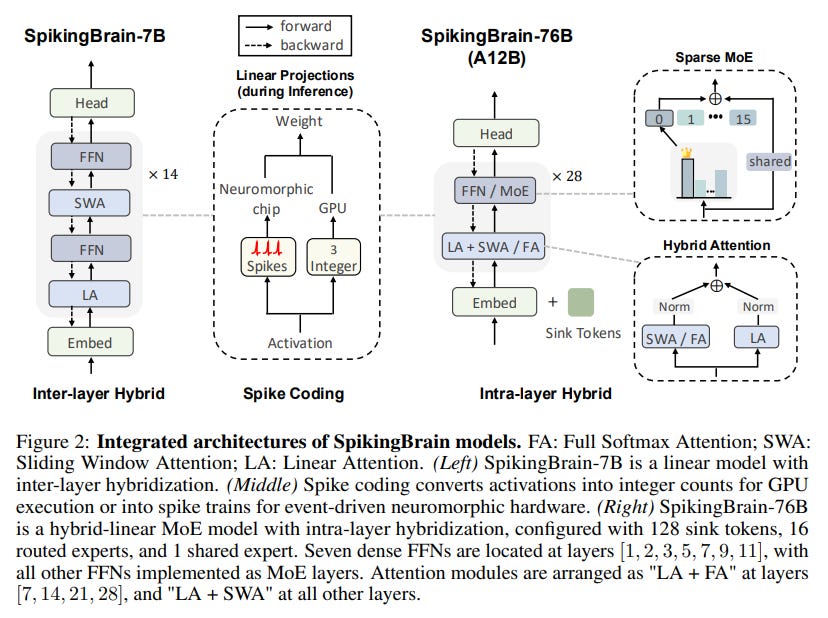

At the core of SpikingBrain are novel architectures designed to overcome the quadratic complexity of standard softmax attention. The authors introduce two models: the purely linear SpikingBrain-7B and the hybrid-linear SpikingBrain-76B, which uses a Mixture-of-Experts (MoE) design. Both based on the Qwen2.5-7B-base checkpoint. It’s interesting, another recent parameter-efficient model K2-Think was also based on the Qwen2.5 base model.

Hybrid Attention Mechanisms: Instead of relying solely on one attention mechanism, the models employ a hybrid strategy. This architectural choice reflects a key design trade-off: SpikingBrain-7B's inter-layer approach creates a purely linear model optimized for maximum long-context efficiency, whereas SpikingBrain-76B's intra-layer hybrid design is engineered to better balance this efficiency with raw predictive performance by retaining some full softmax attention capability (Figure 2).

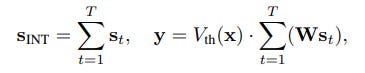

Adaptive-Threshold Spiking Neurons: Moving beyond continuous activations, the models incorporate a simplified spiking neuron model. This is a crucial step towards event-driven, low-power computation.

A dedicated spiking strategy encodes activations as equivalent integer values and spike sequences. This method can be applied both during and after training, converting the activations of large models into spikes. To further improve energy efficiency, the authors quantize both model weights and the KV cache to INT8 precision in conjunction with the spiking process. Integrated with SpikingBrain’s lightweight conversion pipeline, this approach requires no full fine-tuning; a small calibration set is sufficient to optimize quantization parameters. For SpikingBrain-7B, the entire optimization process takes about 1.5 hours on a single GPU with 15 GB memory, significantly reducing deployment cost while preserving accuracy.

The activation spiking scheme follows a decoupled two-step approach: i) Adaptive-threshold spiking during optimization: single-step generation of integer spike counts while maintaining appropriate neuronal firing activity. ii) Spike coding during inference: expansion of spike counts into sparse spike trains over virtual time steps. This approach enables the integer-based formulation to support computationally efficient optimization on GPUs, while the expanded spiking formulation provides event-driven, energy-efficient inference when combined with specialized hardware.

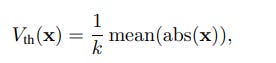

During optimization, an integer spike count S_INT is generated from the accumulated input potential V_T and a dynamic firing threshold V_th(x):

During inference, this integer count is expanded into a sparse spike train with values {0, 1, −1}. The process is formulated as:

Because each st takes values from {0, 1, −1}, matrix multiplications are replaced by event-driven accumulations, thereby improving computational efficiency. The adaptive threshold is a key departure from conventional Leaky Integrate-and-Fire (LIF) neurons from Spike-driven Transformer (https://arxiv.org/abs/2307.01694, https://arxiv.org/abs/2404.03663), which the paper notes can suffer from instability in large models due to fixed firing thresholds and complex temporal dynamics. By simplifying the model and making the threshold dynamic, the authors create a system that is more stable and efficient for large-scale training.

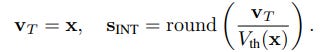

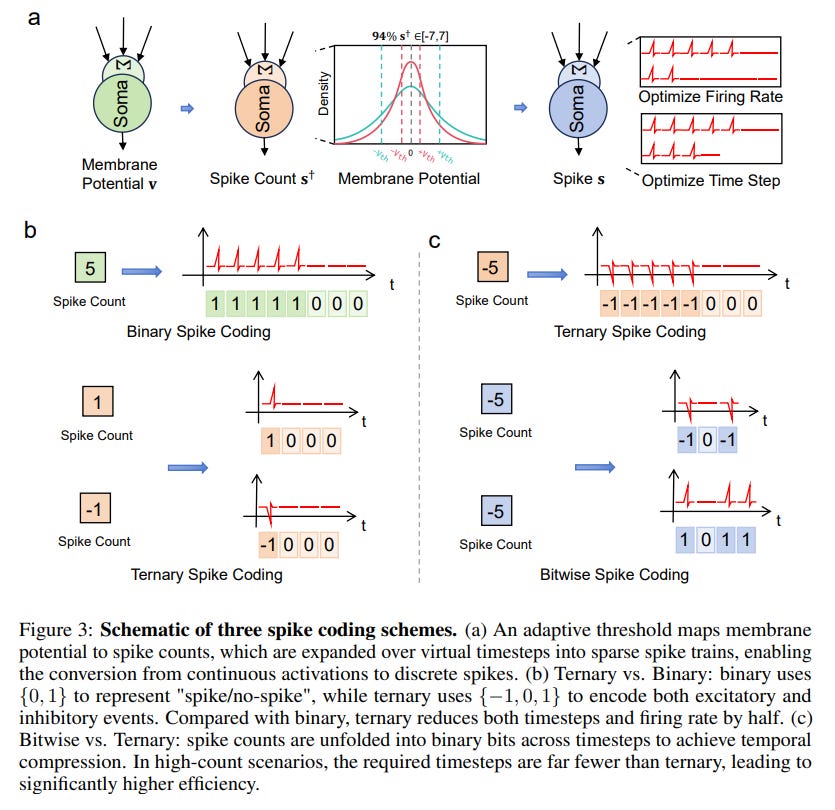

The framework supports multiple spike coding schemes, each with different trade-offs (Figure 3).

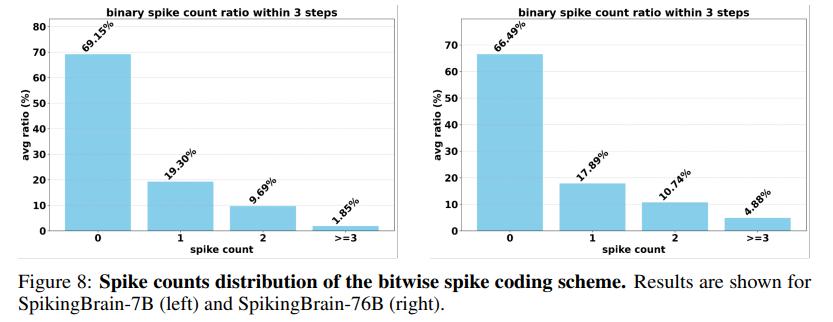

Binary coding {0,1} is the simplest; Ternary coding {-1,0,1} improves sparsity by adding inhibitory spikes (-1); and Bitwise coding dramatically compresses the time dimension, making it highly efficient for neuromorphic hardware that needs to represent large activation values precisely. For instance, a count of 256 requires 256 consecutive time steps in binary coding, 128 in ternary coding, but only 8 steps in 8-bit bitwise encoding.

Mixture-of-Experts (MoE): To scale model capacity efficiently, SpikingBrain-76B incorporates a sparse MoE architecture. It leverages an "upcycling" technique (https://arxiv.org/abs/2410.07524) where a pre-trained dense FFN is replicated across all experts, with weights rescaled to maintain output consistency at initialization.

2. Efficient Algorithmic Optimizations

A key innovation is the conversion-based training pipeline, which drastically reduces data and compute requirements. The methodology is grounded in the theoretical correspondence between attention maps: Sliding Window Attention is a sparsified version of the softmax attention map, and linear attention is a low-rank approximation. This allows for initializing the models by directly transferring weights from a pre-trained Transformer. The continual pre-training process requires only ~150B tokens—less than 2% of the data needed to train from scratch.

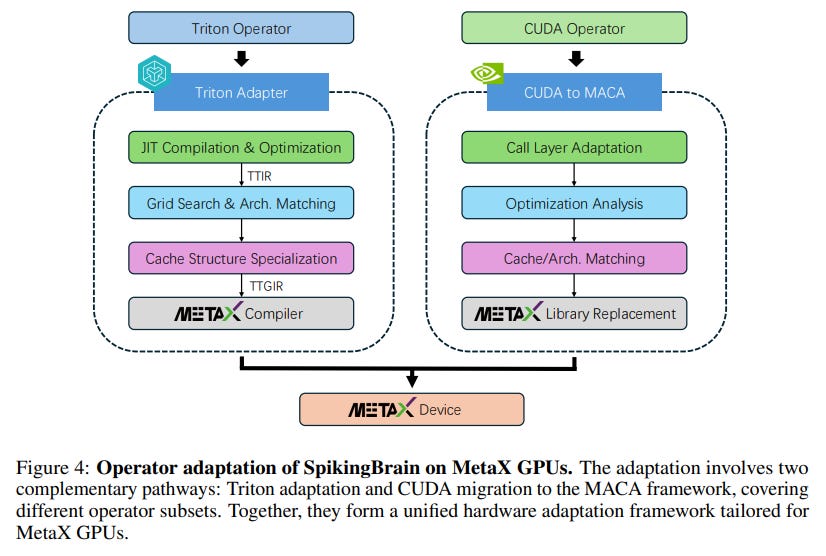

3. System Engineering for Non-NVIDIA Hardware

A standout contribution is the successful large-scale training on a non-NVIDIA cluster of MetaX C550 GPUs. This required extensive system engineering, including custom operator adaptation and sophisticated distributed training strategies (Figure 4).

To ensure stability, the MetaX software stack was enhanced with hardware-aware features like "Hot-Cold Expert Optimization" to manage communication hotspots and the "DLRover Flash Checkpoint" technique (https://arxiv.org/abs/2304.01468) to reduce I/O time by 85% and enable rapid recovery.

Experimental Results: Efficiency Without Sacrificing Performance

The paper presents a compelling set of results that validate its approach.

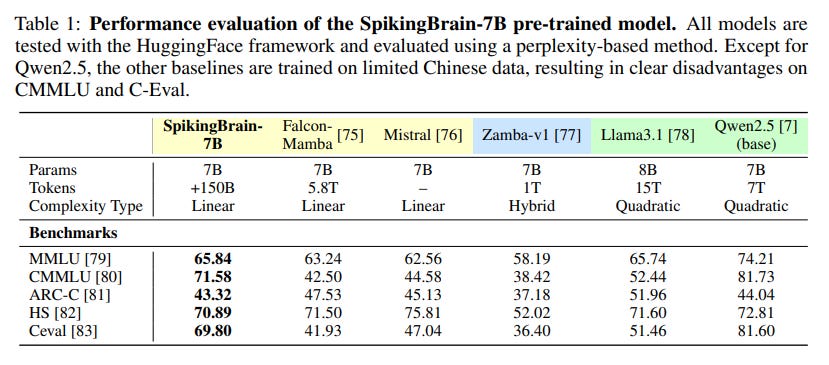

Downstream Performance: The SpikingBrain models achieve performance comparable to strong open-source baselines. SpikingBrain-7B is competitive with models like Mistral-7B (https://arxiv.org/abs/2310.06825) (Table 1).

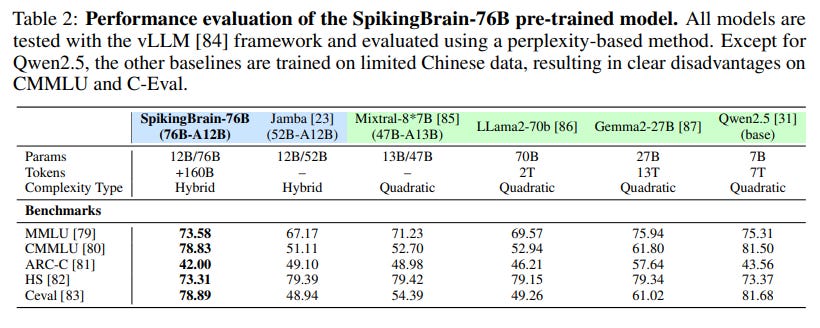

The larger SpikingBrain-76B nearly closes the performance gap with its base model and is competitive with models like Mixtral-8x7B (https://arxiv.org/abs/2401.04088) and Llama2-70B (https://arxiv.org/abs/2307.09288) (Table 2).

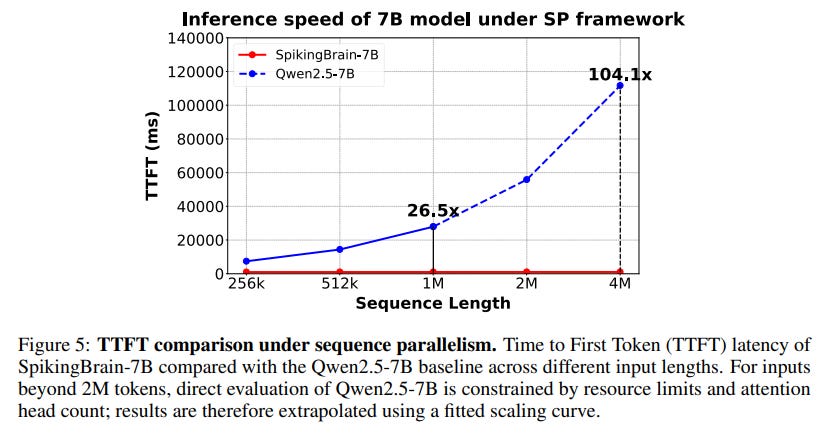

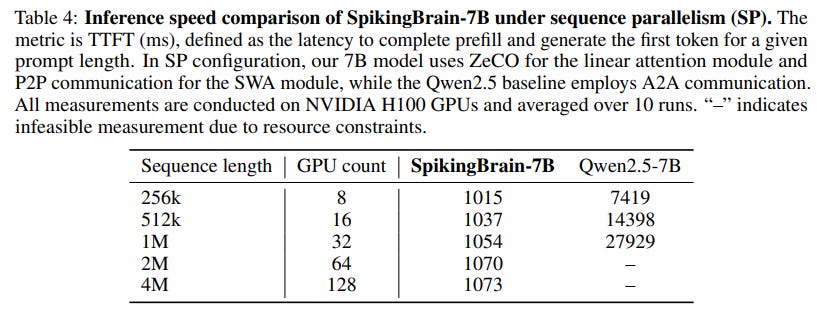

Long-Context Efficiency: The efficiency gains are dramatic. In inference, SpikingBrain-7B achieves a 26.5x speedup in Time-to-First-Token (TTFT) at a 1M token context, with an extrapolated speedup of over 100x at 4M tokens compared to its Qwen2.5-7B (https://arxiv.org/abs/2412.15115) baseline (Figure 5, Table 4).

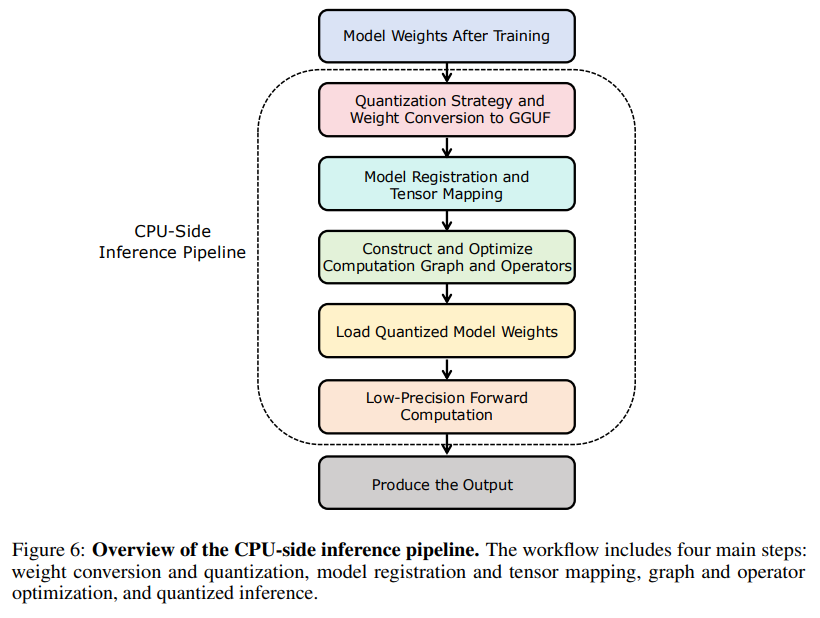

CPU and Edge Deployment: The benefits extend to resource-constrained environments.

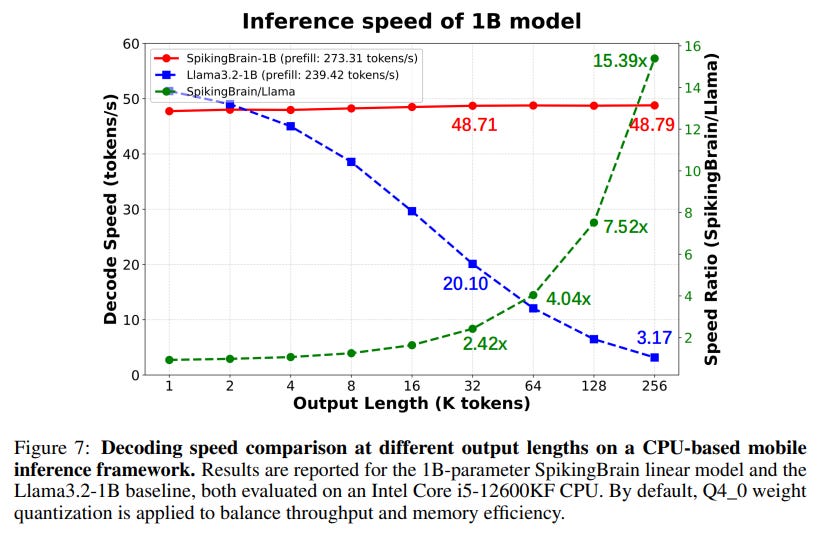

A compressed 1B SpikingBrain model deployed on a CPU achieves a 15.39x speedup over a Llama3.2-1B baseline at a 256k sequence length (Figure 7).

Sparsity and Energy Savings: The adaptive spiking scheme achieves an overall activation sparsity of 69.15% (Figure 8). The authors estimate a 97.7% reduction in energy consumption for MAC operations compared to standard FP16 execution, highlighting the immense potential for sustainable AI.

Limitations and Future Directions

The authors are transparent about the method's limitations. The pure linear model (SpikingBrain-7B) does exhibit a performance gap compared to its base model, a trade-off for its extreme efficiency. Furthermore, the full low-power benefits of the spiking mechanism can only be realized on specialized asynchronous neuromorphic hardware.

Conclusion

The SpikingBrain technical report offers a valuable and comprehensive contribution to the field of AI. It moves beyond incremental architectural tweaks to present a holistic, full-stack vision for efficient and scalable large models. This work compellingly demonstrates that the path to more capable and sustainable AI lies not just in scaling up, but in scaling smarter. SpikingBrain suggests the future of AI may be less about building bigger digital calculators and more about finally learning from and emulating the profound computational efficiency of biological intelligence.